Mexican rocks and minerals collecting after World War II was exciting as millions of collector specimens were mined and sold. During the war, Mexico’s mines produced the metals needed for the war effort. Imagine the wonderful specimens that went to the smelters at that time.

When the war ended, mines powered down, leaving countless miners jobless, miners who knew the underground workings and minerals without an opportunity to use their skills. Surplus war materials like Jeeps were sold and military veterans, among others, combined the availability of four-wheel-drive vehicles with the opening of more federal lands and headed into the great outdoors, and the mineral collecting hobby grew rapidly. This rapid growth created a ready market for minerals, which prompted Mexican miners to go back to work, with some even forming mineral collecting consortiums.

Mexican Rocks & Minerals in High Demand

Instead of mining metal ores, the miners mined mineral specimens of every variety. Mineral dealers located close to the border became a ready market for access to minerals from Mexico. As miners realized they could make a living underground, the flow of minerals from Mexico’s mines became a flood by the early 1950s.

The volume of minerals coming out of Mexico was so great that some dealers became wholesale marketers operating in or near border towns like El Paso and Tucson. This interest provided Mexican miners a ready outlet for their efforts. In a short time, dealers and collectors began driving to Mexican mining towns to buy directly.

Wholesale dealers like Tucson’s Susie Davis sold minerals by the flat and never lacked good stock. Miners catered to visitors but always kept the better specimens under the bed. People who visited the Tucson Show by 1960, especially show dealers, planned ahead and drove to Mexico after the show to restock.

Today, with the growth in illegal activities and a slowdown in mining, the halcyon days of rockhounding in Mexico are more past than the present. Solo trips are less encouraged than in years past.

Mina Ojuela

In spite of some difficulties collecting in Mexico today, there are still plenty of fine Mexican minerals available, which is a testament to the huge quantity of specimens that poured forth in the last half of the 20th century. Miners are still working underground, and once in a while, a big hit happens.

Among the most active mines during the heyday was Mina Ojuela, Mapimí, Durango. It is credited with producing some of the world’s finest examples of species like adamite, legrandite, and koettigite. It soon became the darling of Mexico’s mineral business 50 years ago, along with Santa Eulalia, Zacatecas, and San Luis Potosi. There are several mines around Mapimi, but Ojuela was the first in the Durango area. Over time, underground tunnels eventually interconnected the mines, so a miner might be digging in one mine but credit his find to Ojuela often to keep secret where he actually found the minerals.

Mina Ojuela’s Specimens

Mina Ojuela was discovered in 1598 by Spaniards looking for riches. The ore vein they spotted was high on the wall of a limestone canyon, which created a problem. Reaching the ore was tough enough, but to actually mine the ore presented a major elevation challenge and an amazing feat of effort.

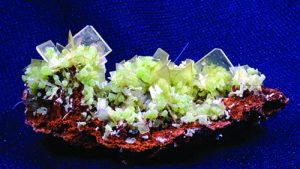

Mina Ojuela’s reputation as a specimen producer is due to the number of species it produced. The variety of species reads like the index of a mineral book. Until Mina Ojuela, adamite was a non-descript hydroxide zinc arsenate of modest color and crystal size.

The type locality was Chañarcillo, Chile. The ancient silver at Lavrion, Greece, produced decent adamite as well, but it was not until the brilliant green crystal sprays of adamite from Mina Ojuela came out in huge quantities that adamite was a must-have mineral. Its crystals are in a fan-like shape or fat ball-like crystal clusters, single crystals and sprays all on a contrasting dark brown iron oxide matrix. The quantity found here was astounding.

Another mineral found at Mapimí is olivenite, hydrate copper arsenate. The only difference between olivenite and adamite is the metal within; in one, it’s copper, and the other, zinc, which are compatible and can easily replace each other. Adamite is green thanks to a trace of copper in it. When copper replaces even more zinc, it is cuproadamite. Russian scientists went further in 2006 and found that if enough copper replaces zinc in some cuproadamite, it forms a new species, zincolivenite. Is your cuproadamite really zincolivenite? Ask Mother Nature.

Mexican Rocks & Minerals

The specimen-producing mines of Mexico are all known. The Spaniards started them out as silver mines and some produced wonderful silver sulfosalt minerals like acanthite, polybasite, tetrahedrite, tennantite and bournonite, all collector minerals. These same mines did not gain a reputation for producing native silver specimens except for Batopilas mine, Sonora. The vast majority of the silver mines had the metal argentiferous galena, sulfosalts, and other collector minerals in the deposits. These old Spanish silver mines became major sources of fine collector minerals for decades in the 20th century as local miners became skilled mineral specimen miners.

The Batopilas mine, Chihuahua, produced fine native silver specimens in some quantity when opened in 1632 by the Spaniards, who found the local native people working it. Even today, this mine is known among collectors for its fine twisted wires and crystals of silver. Spaniards were only interested in mining the silver, so other minerals were bypassed, leaving them for collectors who followed.

Sonora & Chihuahua

Each of Mexico’s states is known for a particular mineral species. Sonora is famous among the lapidary crowd for agate. Among collectors, wulfenite from Sonora and nearby Chihuahua is well known. Chihuahua was made famous by National Geographic in 1921 when it featured the giant selenite crystals in the Cave of Crystals/Cave of Swords. It revisited the site again in the 1990s. This second visit was broadcast on television as the selenite cave had the world’s largest selenite crystals — 40 feet long!

Zacatecas & San Luis Potosi

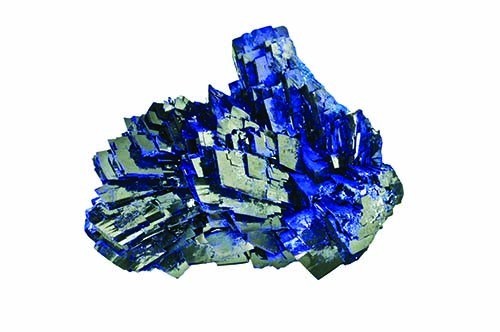

The state of Zacatecas has certainly produced superb collector minerals including azurite, galena, sphalerite, chalcopyrite and other metal ores. And, of course, silver species and gold have also come from here.

San Luis Potosi is very well known among collectors due to the superb poker chip calcite specimens it yielded in recent years. These specimens rival the historically important calcites from Germany. Quantities of large and sometimes colorful danburite crystals still come from here now and then as well.

Sinaloa

In recent years, Sinaloa really caused a stir among collectors when the mine at Choix produced large quantities of colorful botryoidal smithsonite. Specimens up to a foot across were mined, and the color range seemed endless, from white to pink to yellow, blue, and green in various tints. Many of the Chiox smithsonite was easily mistaken for the famous blue specimens from Kelly Mine, New Mexico.

The range of collector minerals from Mexico in the last 75 years is simply amazing. From gorgeous Las Vigas amethyst crystal groups to recent Milpillas mine azurites to rare silver sulfosalts and everything in between, these finds enhance mineral collections worldwide.

The millions of mineral specimens brought to grass in Mexico have played a huge role in the growth of this hobby throughout the world in these last decades, and there is no end in sight.

This story about Mexican rocks and minerals previously appeared in Rock & Gem magazine. Click here to subscribe. Story by Bob Jones.