The pyrite mineral is often called fool’s gold, and it’s easy to see why. With its brassy metallic shine, it resembles gold but is far more abundant and affordable. Beyond its glittering appearance, this mineral has a fascinating history, practical uses, and collectible appeal, making it a favorite among mineral enthusiasts, paleontologists, and jewelry lovers alike. Let’s explore the gold look-alike of pyrite, how it differs from gold and why it makes for one great gift.

Pyrite Mineral vs. Real Gold

With its golden color and metallic shine, pyrite resembles gold. But gold is much more valuable and rare, even if 2,500 metric tons are mined each year. Empires have been built upon it. People have fought over it. Its rich luster polishes to a high sheen that doesn’t tarnish, making for attractive jewelry. Highly valued, gold holds much symbolism: Olympic winners are gold medalists, we hold things to a “gold standard,” and good behavior is golden.

What Is Pyrite?

To mineralogists, pyrite FeS2 is iron sulfide. Its resemblance to gold is superficial and fools no experienced collector. While pyrite may be golden in color, it’s brassy and leaves a greenish-black streak on a streak plate; real gold leaves a golden streak. Also, gold is soft (Mohs hardness 2.5 to 3) and malleable. Pyrite is hard (Mohs hardness, 6.5) and brittle. Simply hit your prized specimen with a hammer. If pyrite, it shatters. If gold, it flattens. So much for your specimen, but at least you’ll know!

As the most abundant sulfide mineral in the Earth’s crust, pyrite is widespread in rocks of all sorts—igneous, metamorphic, sedimentary—and forms in varied conditions, from low-temperature acidic environments in ocean sediments to hot hydrothermal environments within rocks.

Pyrite Mineral in History & Folklore

Resemblance to gold led to pyrite’s nickname of fool’s gold, an epithet traced to the California gold fields, where excited greenhorns offered to buy drinks for all while slamming down chunks of pyrite. The term now applies to anything that appears valuable but is not. Both Romans and Shakespeare said it: Non omne quid nitet aurum est: “All that glitters is not gold.”

However, not everyone has agreed. Ancient Egyptians worshipped Amun, who sported ram horns on his head; thus, coiled pyritized ammonite fossils were considered lucky charms. During the Islamic Golden Age, philosopher and physician Ibn Sina (c. 980 – 1037 C.E.) contended that pyrite could shield an infant from fear. In a similar belief from Thailand, sacred pyrite battles demons and black magic. Contemporary New Agers see it as a protective stone energizing areas around it.

Pyrite Mineral and Alchemy

Observations by Persian scholar Al-Razi (865-925 C.E.) led to alchemists of medieval Europe, who hoped to transform ordinary metals into gold. Per prevailing thought, metallic ores originated deep within Earth, then journeyed to the surface. The longer the journey, the more refined the metal became until it achieved golden perfection. Thus, alchemists believed pyrite just needed the right sort of nudging in a crucible to convert it to gold.

Alchemists weren’t that far off. Some pyrite deposits do contain gold. Albertus Magnus (c. 1200-1280 C.E.), one of the greatest philosophers of the Middle Ages, noted that when crushed and mixed with mercury, pyrite sometimes left behind an amalgam that converts to gold when heated to vaporize the mercury. To alchemists, this proved pyrite could be turned to gold, little realizing that existing gold within the pyrite had simply been freed through cupellation.

Alchemists were variously embraced (mainly by rulers wanting more gold in the treasury) and ostracized to the extent of being burned at the stake. Eventually, their quest to convert the ordinary to the extraordinary, combined with scammers, led to a bad rap. With the Renaissance came more serious experimental folks tilting toward science as practiced today. But the fantastical pseudoscience of alchemy helped pave the way toward the real and helpful science of chemistry, and both pyrite and gold played prime roles.

Pyrite’s Practical Uses

Per geochemist David Rickard, pyrite is not just a mineral; it’s “the mineral that made the modern world.” While alchemists sought to convert pyrite to gold, others sought practical uses, so many that a whole book could be written about it. That’s just what Rickard did in Pyrite: A Natural History of Fool’s Gold. Here’s a tiny sampling of what’s in that book.

Perhaps most significantly, pyrite gave Stone Age peoples a portable toolkit for starting fires. Stuff a pouch with pyrite and flint and a bit of tinder, and wherever you are, you can start a fire, given that pyrite releases a spark when struck with flint. This method of fire-starting is considered one of the greatest advances in the history of humanity. It also advanced weapons development in the 16th century. A steel wheel rotating against pyrite in wheel lock pistols produces sparks to ignite gunpowder. So pyrite gave us not only fire to roast our boar but the means to bring it down.

Rickard further notes that pyrite and its sister sulfides were mined in ancient and medieval times as major sources of sulfur, copper, lead, arsenic and other valued mineral commodities. It continues to be mined to produce sulfuric acid and iron sulfate for chemical, fertilizer and pharmaceutical industries. It’s used in the paper industry to produce the pages you’re now reading! In our high-tech world, pyrite is being explored as an abundant, inexpensive material for solar panels. Finally, some pyrite deposits remain important sources of real gold.

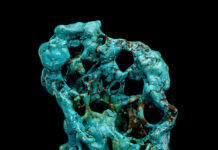

Pyrite for the Mineral Collector

At last, we come to the fun aspect of pyrite. Collecting it! Here’s why it’s perfect for anyone on your holiday gift list. It’s distinctively attractive, common worldwide and usually inexpensive, and takes varied forms within the isometric system. Those forms include cubes, octahedrons, pyritohedrons and more. Variations in crystal shape are due to differences in conditions when a specimen formed, and mineralogist James Dwight Dana (of the Dana classification system of mineralogy) described no less than 85 forms! Thus, per the late John Sinkankas, it’s the perfect mineral for the “single-species specialist.” As a nice bonus, pyrite often forms in association with other minerals to beautiful effect.

While pyrite is found worldwide, two places stand out. Navajún, Spain, is famed for cubic crystals, both large individual specimens and interesting clusters. And Peru’s Huanzala Mine produces delightful octahedrons. Specimens from both regions are a must in any collection.

Pyrite Mineral in Fossils & Paleontology

So the person on your gift list collects fossils, not minerals? No problem! Pyrite gives a gift that covers both worlds. Pyrite and its twin sister, marcasite, commonly form in ocean sediments where there’s little oxygen (anoxic conditions) and sometimes replace the original shell material of ammonites, brachiopods, and other critters as they fossilize.

Such pyritized seashells and pyritized dinosaur bone fossils have become classics gracing nearly all museum collections. Pyrite replacement has value beyond inherent beauty. It’s provided important revelations for paleontologists. When shales containing pyritized trilobites from New York and Germany have been X-rayed, details of legs, antennae & more have been revealed.

Pyrite Jewelry

The person on your gift list says she’s not a collector yet drips jewelry? Perfect! Pyrite has been used in jewelry for thousands of years, showing up in excavations from civilizations as varied as the Inca and ancient Greeks. Pyrite may be faceted, cabbed or cut into beads.

In shopping for pyrite jewelry, you may find yourself confused. That’s because jewelers market pyrite as marcasite. What’s up with that? Pyrite and marcasite are polymorphs; that is, they have identical chemical makeup but different crystal structures, and marcasite’s structure is too brittle for lapidary work. For hundreds of years, the terms pyrite and marcasite were used interchangeably. While mineralogists separated the two in 1845, within the jewelry industry, marcasite stuck as the term for anything made of pyrite.

Jewelry featuring faceted pyrite was popular in Victorian England after the death of Prince Albert when Queen Victoria replaced precious gems with more somber stones. Vintage Victorian and Art Nouveau “marcasite” jewelry is common at flea markets and the online marketplace. It was often cut with four or six facets and a flat back and set in silver. Pyritized ammonites are used as-is for pendants. Marcasite (real marcasite) appears as plume-like inclusions in agate that cuts into lovely cabochons, the prime example being Nipomo Bean Field Agate of California.

Preserving Your Pyrite

Collectors of pyrite face a problem that goes by several names: pyrite disease, decay or rot. Over time, iron sulfide combines with moisture and oxygen to create hydrous iron sulfate, which expands and causes a specimen to fracture. It also releases corrosive sulfuric acid. In my collection, a pyrite sun cracked and crumbled while also corroding the paper label stored with it. A pyritized ammonite developed a white crust and discolored the cotton cushioning it.

Pyrite rot is exacerbated by conditions of high humidity. Kept away from damp air, specimens generally last a long time, but there’s no way to stop the process once started. Remove deteriorating specimens before nearby specimens are affected. Chemically unstable marcasite is especially prone; you may see it turn green before crumbling into a white powder with a distinctive smell from sulfur dioxide gas. By the way, this isn’t just some esoteric issue for rock collectors. The release of acid when pyrite oxidizes is of major concern for contamination of water flowing out of mines.

Why doesn’t all pyrite dissolve to dust in a mineral cabinet? The process is generally slow, and pyrite surfaces evolve thin layers of iron oxide, thus protecting against further oxidation. Well-crystalized specimens are normally stable, but monitor any specimens formed as sedimentary concretions.

The Pyrite Mineral FamilyWhile pyrite may be the most abundant sulfide mineral, it’s just one of the large and varied pyrite mineral group. Around 1550, during the time of Georgius Agricola (author of the classic mining tome De Re Metallica), the term “pyrite” was used generically for all metallic sulfide ore minerals. Here are a few cousins that have since been differentiated within the pyrite mineral family. Marcasite, FeS2Sometimes called white iron pyrite for a tin-white hue, marcasite is a polymorph of pyrite; they have identical chemical composition but different crystal structures. Pyrite mineral forms isometric crystals; marcasite forms longer, flatter orthorhombic crystals. It’s more brittle and less stable than pyrite. Chalcopyrite. CuFeS2Chalcopyrite (AKA, yellow copper, blister ore) is the main ore of copper. More bronze-like in color than brassy pyrite, chalcopyrite can form as tetrahedral (4-sided) crystals, as bubbly botryoidal clusters, or—more commonly—as compact masses. At 3.5-4 on the Mohs scale, it’s softer than pyrite. Arsenopyrite, FeAsSWelcome to the dark side of the pyrite mineral family, courtesy of a dab of arsenic! Arsenopyrite has the color of bright steel or white silver, tarnishing to dark gray. It’s mined exclusively for its arsenic content to be used as a poison, preservative and pigment. |

Gifting Pyrite

Rather than end on a bummer, I’ll point out that in my collection of over 100 pyrite specimens accumulated over several decades, I’ve only experienced pyrite rot with three. The rest continue to gleam bright and continue to delight. Gift that delight to a loved one!

This article about the pyrite mineral previously appeared in Rock & Gem magazine. Story and photos by Jim Brace-Thompson. Click here to subscribe.