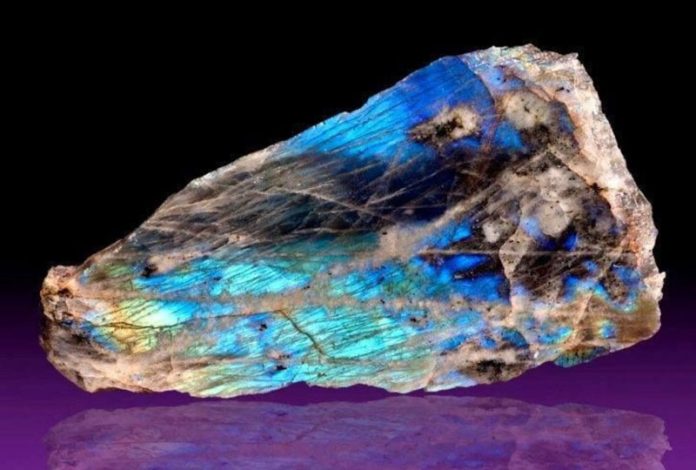

Labradorite mimics the celestial splendor of northern lights with glowing curtains of cyan, green, gold, and magenta. This mineralogical phenomenon called labradorescence, gives this feldspar mineral a multicolored, subsurface, iridescent sheen.

Labradorite’s classic source—its geologic type locality, namesake, and the birthplace of its legends—is the remote coast of Labrador, the northern part of the Canadian province of Newfoundland and Labrador. Labrador is named for the Portuguese mariner Joāo Fernandes Lavrador who, in 1498, braved the region’s subarctic climate to explore its rugged, deeply indented coast.

“Firestone”

In 1771, Moravian missionary Jens Haven founded the coastal settlement of Nain in northern Labrador. Intrigued by the brightly colored stones displayed by the indigenous Inuit, Haven sent specimens to Germany where they became known as “Labrador Stein,” and to England where they were called “Labrador stone” and “firestone.”

As the first new mineral reported from what would become Canada, Haven’s specimens, with their eye-catching colors, attracted great scientific attention in Europe. In 1780, German geologist Abraham Gottlieb Werner, unable to determine the composition of Labrador Stein, erroneously described it as a distinct mineral species.

The first clue toward understanding the chemistry of “firestone” came in 1820, when researchers described the plagioclase feldspar minerals albite (sodium aluminum silicate) and anorthite (calcium aluminum silicate). Soon afterward, French mineralogist François-Sulpice Bedant determined that the Labrador specimens were a type of feldspar with characteristics of both anorthite and albite and named them “labradorite.”

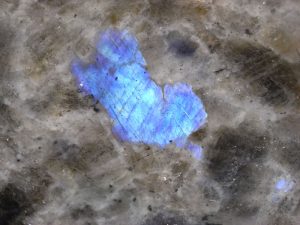

LabradorescenceLabradorescence, a type of mineral iridescence, is caused by the phenomenon of optical interference that occurs when two or more reflected light waves of the same frequency and traveling in the same direction overlap. Optical interference may be destructive or constructive. In destructive interference, out-of-phase wavelengths cancel each other out. But in constructive interference, which is the cause of iridescence, the overlapping waves are in phase and reinforce each other to produce structural or iridescent colors of unusual vibrancy and “purity” that are aptly described as “electric” or “neon-like.” Optical interference is produced when light interacts with two types of surfaces: microscopically thin films and diffraction gratings. Labradorite’s internal layers of twinned, translucent microcrystals produce both thin-film and diffraction-grating interference to create its unusual play of iridescent cyan, green, gold, and magenta colors that vary in hue and intensity as the viewing angle changes. |

Courtesy Wikimedia Commons

Properties and Occurrence

By 1850, mineralogists had correctly categorized labradorite as the labradorescent gem variety of the plagioclase-feldspar mineral anorthite. Anorthite is the calcium-rich end member of the anorthite-albite solid-solution series; albite is the sodium-rich end member. As an intermediate member of this series, labradorite has a 70:30 calcium-sodium composition.

Crystallizing as prisms or tabs, anorthite is transparent to translucent, grayish-white, and has a vitreous luster. A specific gravity of 2.75 makes it slightly denser than quartz. Brittle and with an uneven-to-conchoidal fracture, anorthite has distinct, two-directional cleavage and a substantial Mohs hardness of 6.0-6.5.

Anorthite is the primary mineral component of anorthosite. Anorthosite’s grain size varies with its cooling rate. Gem-quality labradorite forms within anorthosite pegmatites that cool very slowly.

In 1923, Danish mineralogist Ove Balthasar Bøggild showed that labradorite’s vivid, multicolored, subsurface sheen, which he named “labradorescence,” is produced by the phenomenon of optical interference.

Legends of The Light

The bedrock near Nain, Labrador, consists largely of 1.3-billion-year-old anorthosite. The labradorite specimens that Jens Haven sent to Europe in 1771 likely came from a tiny island ten miles south of Nain that the Inuit called Nepoktulegatsuk. The Moravians renamed the island “Tabor Island,” after the biblical Mount Tabor.

Tabor Island consists entirely of anorthosite with scattered pegmatitic bodies of labradorite that vary in size from only a few feet to more than 50 feet in diameter. The island’s most distinguishing feature is a large, exposed, partially quarried pocket of pegmatitic anorthite with an intense blue labradorescence.

The striking similarity of labradorescence to the northern lights had long inspired a host of Inuit legends. One tells of a hunter who saw light imprisoned in a rock. To free it, he struck the rock with his spear, sending some light skyward to become the northern lights; the light remaining in the rock became the labradorescence we see today.

Another legend recounts how the Great Spirit created labradorite to remind the Inuit of the beauty of the northern lights even when they could not be seen during the short summer nights. In yet another tale, the Inuit explained labradorescence as a part of the northern lights that, during a long and particularly bitter winter, froze and fell to Earth.

Courtesy Wikimedia Commons

Quarrying Labradorite

In 1890, American author and adventurer Ralph Graham Taber attempted to commercialize Tabor Island labradorite by operating a small quarry during Labrador’s brief summers. Taber’s labradorite must have been striking, for in 1894 the Smithsonian Institution purchased large display specimens.

But Taber failed to interest jewelry manufacturers, possibly because fracturing from heavy-handed blasting had made much of his labradorite difficult to cut. By the time his quarry closed in 1896, Taber had shipped only about eight tons of labradorite to the United States.

In 1935, the noted Labrador medical missionary Wilfred Thomason Grenfell, hoping to develop an economic asset for the Inuit, sent a six-man expedition to Tabor Island to survey the old Taber quarry. The group gathered and shipped a large quantity of labradorite for test marketing in North America and Europe. The proceeds from its sale benefited the International Grenfell Association, a nonprofit group founded by Wilfred Grenfell and dedicated to serving Labrador’s Inuit.

Small-scale labradorite mining on Tabor Island continues sporadically today. The Labrador Inuit Association now controls the island and regulates all mining and collecting activity. Labradorite has always retained its popularity as the region’s premier gemstone. In 1975 when the Newfoundland and Labrador government voted to designate an official provincial mineral, Tabor Island labradorite was the unanimous choice.

“Blue-Eyes Granite”

Labrador’s labradorite next gained attention in 1986 when a provincial Department of Mines and Energy resource survey determined that an anorthosite exposure on Paul Island (also called Isle of Paul or Paul’s Island) near Nain had commercial potential as a source of architectural or dimension stone.

At Paul Island’s Ten Mile Bay, a massive outcrop of coarse-grained, light-gray anorthosite rock is dotted with quarter-tohalf-inch-diameter anorthite phenocrysts that glitter with a bright-blue labradorescence. Walking past the outcrop reminded one geologist of “winking blue eyes.”

In 1987, an Italian stone company cut, polished, and successfully test-marketed tiles fashioned from Ten Mile Bay anorthosite. However, operating a quarry in northern Labrador would not be easy. Nain, population 1,000, is located just 500 miles below the Arctic Circle. As Labrador’s northernmost permanent settlement, it is far north of the region’s limited road system and accessible only by air or seasonally by sea.

Nevertheless, the Ten Mile Bay Quarry was soon shipping 3,000 tons of labradorescent anorthosite blocks each year to Italy for processing into high-end countertops and tiles that were marketed as “Blue-Eyes Granite.” The name “granite” was technically incorrect, but for marketing purposes, the dimension-stone industry traditionally labels most igneous stone as “granite,” a word synonymous with durability and strength. Although active only from June through September, the quarry was a big boost to Nain’s traditional hunting and fishing economy.

The quarry management soon announced ambitious plans to vertically integrate the operation by cutting and finishing anorthosite in Labrador for direct North American marketing. But the timing was unfortunate: Profits plummeted amid the global economic crisis of 2008 and the quarry closed just two years later.

“Blue-Eyes Granite” remains available today as one of the most distinctive of all interior architectural stones. And the Ten Mile Bay Quarry may still have a future. A Newfoundland entrepreneur has recently acquired quarrying rights and plans to resume production.

Courtesy Nancy Rogers/ NDR Jewelry Design

A Sculpting Medium and Gemstone

In addition to its popularity as an architectural stone, Ten Mile Bay anorthosite has also become a sculpting medium, thanks to the innovative work of Inuit sculptor Gilbert Hay, who was raised in Nain. With few employment opportunities available, Hay supported himself by becoming a self-taught sculptor working in the traditional Inuit media of soapstone, serpentine, whalebone, walrus tusk and caribou antler. When the Ten Mile Bay Quarry opened in the 1990s, Hay turned his attention to what was then an untried sculpting medium—labradorescent anorthosite. Today, Hay’s anorthosite sculptures are featured in such prestigious venues as Birches Gallery of Newport, Nova Scotia (www.birchesgallery.com).

Meanwhile, gem-quality Tabor Island labradorite remains available in fine jewelry created by a small group of Newfoundland and Labrador lapidaries and jewelry designers. Foremost among these are Nancy and Lar Rogers of NDR Jewelry Design in Hare Bay, Newfoundland. Lar cuts and polishes the labradorite rough; Nancy, an expert at silver-wire wrapping, designs and fabricates distinctive labradorite pendants.

Nancy and Lar also use Ten Mile Bay anorthosite to fashion seven-inch-high, miniature inukshuks, stacks of flat, semi-polished stones in a stylized, upright, human “arms-out” configuration. For centuries, the Inuit made inukshuks, some as tall as ten feet, to serve as navigation points, cache markers, and spiritual symbols. For more information, contact Nancy Rogers at nrogers@msn.com.

Regional demand for Labrador’s labradorite has increased steadily as growing numbers of tourists seek souvenirs unique to the province—and that means labradorite specimens and jewelry. But not all labradorite sold regionally is from Labrador. Unfortunately, much is inexpensive Madagascar material that is often sold without disclosure of origin or sometimes even blatantly misrepresented as labradorite from Labrador.

But to residents of Newfoundland and Labrador, “real” labradorite comes only from Labrador itself, the gemstone’s type locality, namesake, and the birthplace of its charming Inuit legends that will forever associate its labradorescence with the northern lights.

This story about labradorite previously appeared in Rock & Gem magazine. Click here to subscribe. Story by Steve Voynick