The Great Diamond Hoax gripped San Francisco in 1872, a city already buzzing with gold and silver fever. Two decades after its historic gold rush, mining excitement from California gold was still running high. The Mother Lode country was still producing gold, Nevada’s nearby Comstock Lode was turning out silver, and newspapers were reporting a huge diamond discovery in South Africa. The hub of all this mining excitement was San Francisco, a booming California city of 150,000 that teemed with bankers, speculators, miners and con artists.

The American West’s next big strike, which might be more gold or silver, or perhaps even diamonds, seemed only a matter of time. If there was ever a fertile field for planting the seeds of a huge mining scam, it was then and there.

Setting the Great Diamond Hoax in Motion

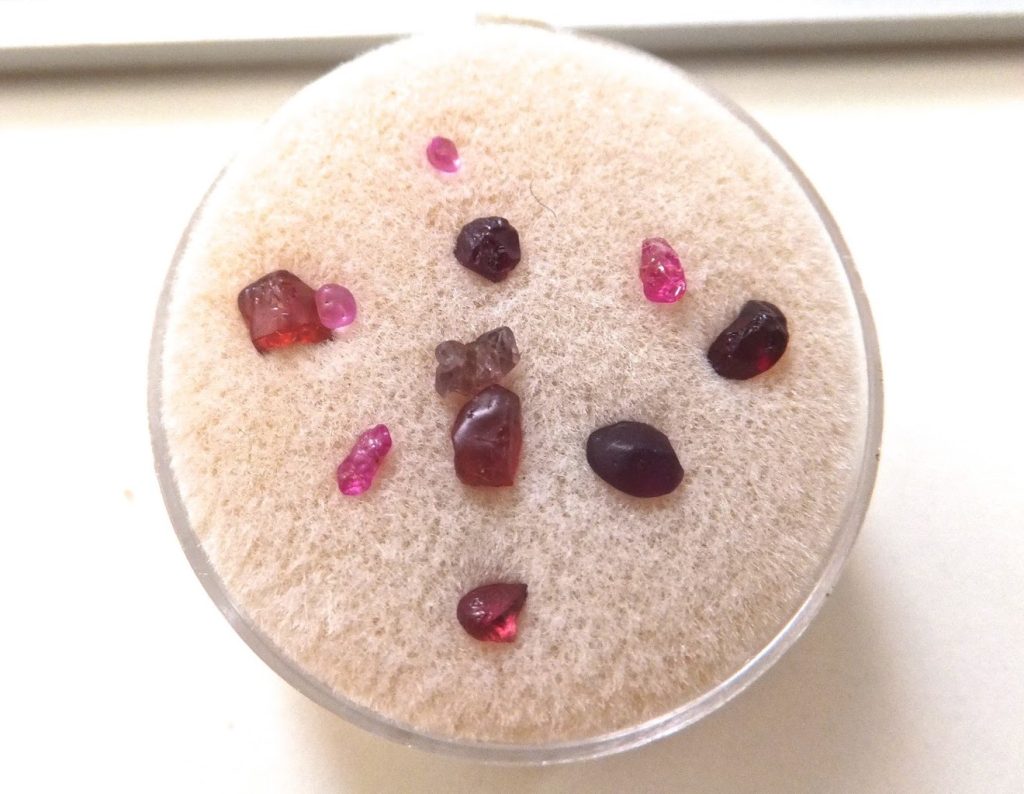

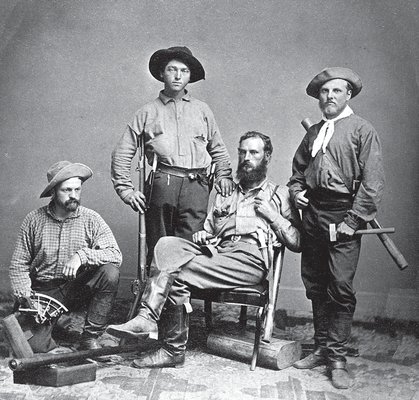

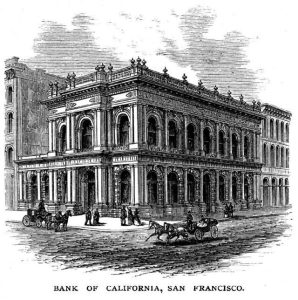

That summer, two roughly dressed prospectors, cousins and native Kentuckians Philip Arnold and John (Jack) Slack walked into San Francisco’s Bank of California to deposit the contents of a heavy buckskin sack. When a bank officer saw that the sack contained not the expected placer gold, but uncut diamonds, rubies and other gemstones, he dutifully reported it to bank president William C. Ralston.

Arnold informed Ralston that he and Slack had collected the stones from a secret site in “Indian territory.” With Arnold’s permission, Ralston hired two prominent San Francisco jewelers to examine the stones. Both pronounced them genuine and of excellent quality.

Sensing an unparalleled investment opportunity, Ralston explained to Arnold and Slack that their discovery had great economic potential, but that development would require considerable financial backing, which, of course, Ralston himself could provide.

Investors Fall for the Scheme

Being an old hand at assessing mining ventures, Ralston had insisted that Arnold and Slack escort two of his trusted business associates to personally inspect the gemstone site. After a 36-hour train ride to southwest Wyoming, the group embarked on a four-day journey on mules during which Ralston’s men were sometimes blindfolded. At the site, the group needed only a day to fill a sack with rough gemstones.

Ralston’s men returned to San Francisco and displayed their finds—8,000 carats of rough diamonds, rubies and other gemstones, which jewelers appraised at $125,000 ($3.1 million in 2024 dollars).

Ralston next shipped a parcel of stones to New York City to Charles Lewis Tiffany, founder and president of Tiffany & Co., the nation’s leading authority on cut gems, who declared the rough stones genuine and estimated their value at $150,000.

Still not quite convinced, Ralston then hired Henry Janin, a well-respected San Francisco mining engineer, to personally inspect the site. When Janin reported that a single ton of surface dirt contained at least $5,000 in gemstones and that a 25-man crew could dig out a million dollars per month, William Ralston swallowed the bait hook, line and sinker.

The Great Diamond Hoax Captures Headlines

Moving quickly, Ralston founded the San Francisco and New York Mining and Commercial Company, then raised $2 million from his wealthy friends and financial contacts. Meanwhile, newspapers from San Francisco to London were headlining the story of “The Great Diamond Fields of America.”

Ralston and his elite group of investors now had no further need for “those two Kentucky bumpkins,” Philip Arnold and Jack Slack. To buy them out, they offered $600,000 in cash and a percentage of future earnings. After initially grumbling in feigned displeasure, Arnold and Slack took the money and disappeared.

(United States Geological Survey)

Clarence King Steps In

As Arnold and Slack made their exit, another key player in this unfolding in the great diamond hoax made his appearance—30-year-old geologist Clarence King, a Yale graduate who had recently led the federal government’s Fortieth Parallel Survey. Completed just months earlier, King’s five-year-long survey had successfully compiled a cartographic record and documented everything from mineralization to vegetation within a 1,000-mile-long, 100-mile-wide tract extending from Wyoming to California.

King was quite concerned because reports of the “Great Diamond Fields of America” appeared to question his own professional competence: He was certain that the purported diamond fields lay within the limits of his own Fortieth Parallel Survey, where he had formally reported that no major gemstone occurrences existed.

King tracked down mining engineer Henry Janin, who described in great detail the site of the gemstone discovery and the nature of the gemstone occurrence. And the geologist didn’t believe a word of it. He knew that diamonds and rubies did not occur in the same mineralogical environments, and also that gemstones, with their considerable densities, would be found at depth rather than on the surface. And given Janin’s descriptions of topography, geology, hydrology and vegetation, King had a good idea of just where the site was.

How the Great Diamond Hoax Was Revealed

Accompanied by several of his experienced survey men, King immediately traveled to Wyoming, then embarked on a five-day, 150-mile-long mule journey. He knew he had found the site when he noticed a crude sign nailed to a tree. The sign claimed water rights from a nearby creek and was signed by Henry Janin.

King found diamonds everywhere, most, he noted with a smile, in crevices that appeared to have been made by sharp instruments. One of his survey men with experience in the new South African diamond fields made an even more telling discovery—a rough diamond that had been partially faceted. “Look, Mr. King,” he joked, “this field not only produces diamonds, it cuts them, too.”

In San Francisco, King didn’t mince words with William Ralston, stating: “… the new diamond field, upon which are based such large investments and such brilliant hopes, is utterly valueless, and yourself and your engineer, Henry Janin, are victims of an unparalleled fraud.”

Several investors, seeking time to unload their suddenly worthless stock, attempted to bribe King not to disclose this revelation. King rejected the bribes and instead supported his conclusion with ten solid scientific observations, one being that he had found “… four distinct types of diamonds, oriental rubies, garnets, spinels, sapphires, emeralds and amethysts—an association of minerals I believe of impossible occurrence in nature.”

Still clinging to a thread of hope, Ralston sent King and another group of “experts” back to the site for a final survey, which merely confirmed King’s initial assessment that the diamond fields were a gigantic hoax. After Ralston’s public admission that he had been duped, newspapers went wild with headlines about the great diamond hoax, like “Diamond Fiasco!” and “Mammoth Diamond Fraud.”

Scandal and Ruin in San Francisco

With his reputation crumbling, mining engineer Henry Janin rushed back to the diamond fields only to confirm his own folly. Unable to personally face William Ralston, he confessed his error by telegram, then quietly left San Francisco.

In New York City, a red-faced Charles Lewis Tiffany admitted that he, while an authority on cut gems, knew nothing of rough gemstones and had grossly misjudged the value of Ralston’s samples. Just two years later, to avoid ever again committing such a blunder, Tiffany would hire as an advisor a young gemstone aficionado named George Frederick Kunz, who would go on to earn recognition and respect as America’s first gemologist.

Although William Ralston became a laughingstock, he partially salvaged his reputation by returning money to his investors and absorbing the entire huge loss himself. The fraud contributed significantly to the failure of his Bank of California in 1875. The day after his board of directors demanded his resignation, Ralston’s body was pulled from San Francisco Bay, an apparent suicide.

Clarence King emerged from the sordid affair as a folk hero. From their pulpits, preachers drilled home sermons on the virtue of honesty, using King as their shining example. Meanwhile, the federal government was busy creating a single agency to oversee all future geological surveys. An uproar arose over who would receive the political plum of becoming the new agency’s first director.

King, a mere field geologist with no inside political connections, had little chance.

But dozens of millionaire California businessmen, top-level politicians and former Civil War generals, all with heavy political clout, suddenly appeared in King’s corner. The geologist had saved them from further embarrassment and financial loss in the Diamond Hoax, and now it was time to show their gratitude. On March 3, 1879, Clarence King was appointed the first director of the United States Geological Survey.

(W. Dan Hausel)

The Men Behind the Great Diamond Hoax

After the great diamond hoax was exposed, investigations revealed that Arnold had worked as a bookkeeper for the Diamond Drill Company of San Francisco, a manufacturer of diamond-studded drill bits. Seeing (and likely stealing) heaps of cheap industrial diamonds had planted the idea of a gemstone fraud. Arnold had also traveled to London and Amsterdam to purchase rejected African diamonds literally by the pound. The “rubies” used in the hoax were either inferior Burmese material or pyrope garnets that Arnold had bought from Native Americans in Arizona.

Ralston’s private detectives later tracked down Arnold in Elizabethtown, Kentucky, where he was the president of his own bank and living well in a fine house with his wife and children. Kentucky refused to extradite its native son and Arnold eventually repaid a mere $150,000 in return for immunity from further legal action. He died several years later from complications following a gunshot wound received in a quarrel with one of his bank employees.

Jack Slack managed to elude Ralston’s detectives. He turned up much later as a small-town undertaker in White Oaks, New Mexico, where he died peacefully in 1896. The Great Diamond Hoax was not the nation’s first mining fraud, nor its last, but it was its best. It had worked because of the nation’s profound gemological ignorance regarding rough gemstones, a shortcoming that Philip Arnold and Jack Slack had recognized and cleverly exploited.

This story about the great diamond hoax previously appeared in Rock & Gem magazine. Click here to subscribe. Story by Steve Voynick.