Zinc headstones, also known as “zinkers,” may look like stone at first glance, but their bluish-grey shimmer gives away their secret—they’re made of 99% pure zinc. These 19th-century monuments, popular after the Civil War and prized for their durability, were marketed as “white bronze” and sold by traveling agents across the country. Today, they stand as haunting relics of American cemetery history—metal monuments that outlasted marble rock, granite, and time itself.

Zinkers in Pop Culture

“They’re coming for you, Barbra…”

Who doesn’t recognize this line from the opening cemetery scene of ‘Night of the Living Dead,’ as siblings Barbra and Johnny run for their lives among the tombstones and zombies?

They were too distracted to appreciate passing by cemetery zinkers, those blue-grey headstones that, at first blush, you assume are stone but with (ahem) a little digging, might learn are actually white bronze monuments of 99% pure zinc.

What Are Zinc Headstones (or Zinkers)?

According to the Historic Congressional Cemetery that preserves, promotes and protects our historic and active burial ground, zinkers (or zincers) were made from about 1870 to 1914, and grew in pragmatic popularity around the Civil War, with production peaking in the late 1880s.

The Monumental Bronze Company of Bridgeport, Connecticut, was responsible for nearly all 99% pure zinc (White Bronze) monuments found in U.S. cemeteries; its subsidiaries also had names for their cast zinc: American Bronze in Chicago, and Western White Bronze in Des Moines.

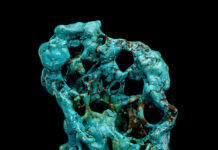

You won’t find the same color headstones now that traveling salesmen pitched in 19th-century catalogs. When exposed to air, zinkers develop zinc carbonate, turning white monuments a bluish-grey. But what really sets zinkers apart from other headstones in older U.S. cemeteries is that they are hollow, which (fun fact) provided a clever and expedient place to hide booze during Prohibition.

How Zinc Headstones Were Made

Zinkers were molded into non-metallic metal sheets, shipped from the factory, and assembled later by fusing pieces together using hot zinc. In an attempt to resemble real stone, zinkers produced in the late 1880s were sandblasted to roughen the surface, then treated with a metal finishing process called “steam bluing,” which consisted of covering the surface with a thin film of linseed oil, then hitting the surface with steam under a minimum pressure of 50 psi.

Spotting and Saving the Details

What also gives these gravestones away is the bottom, where four peg holes can be found to attach a zinker to its cement or granite foundation. According to the Friends of Mount Holyoke Cemetery, a special tool, looking vaguely like a screwdriver but with a negative rosette bolt head where the end of the screwdriver blade would be, was used to loosen and tighten the cast zinc nuts.

“These grave markers were sold cheaply and, in a wonderful twist of irony, have lasted longer than those which were considerably more expensive,” posted a photographer on Flickr after discovering the zinker of Fred Hynick, Nov. 18, 1881-Dec. 15, 1898, in the Old Maple Grove Cemetery in Hoosick Falls, New York. The headstone, embellished with roses, read, “No pain, no grief, no anxious fear, can reach our loved one sleeping here.”

“Although many of these monuments are around a hundred years old, most are in much better shape than granite and marble stones. This is partially due to the durability of zinc,” explains Kymberly Mattern, grounds conservation manager with the Congressional Cemetery.

But a real threat to zinker headstones sounds even scarier: creeping.

“This occurs when the weight of the zinc at the top of the monument puts pressure on the lower section, causing the monument to slowly move over time,” says Mattern, adding, “This can cause a crooked baseline on a monument or tiny cracks. The best way to address this is to install an inner armature to help the base support the weight of the top. Sometimes, weak or brittle parts of the zinc break or separate from the seam. This can be fixed by soldering or using an epoxy or resin.”

Where to Find Historic Zinc HeadstonesEven Reddit calls Find a Grave the “best place on the internet” to look for burial information and that means zinkers, too. In fact, Find a Grave has an All-Zinkers Virtual Cemetery (who knew of such a thing?) where you can see and learn about specific headstones: findagrave.com/virtual-cemetery In its intro to zinkers across the United States, Find a Grave writes, “The fancy White Bronze name was a marketing ploy to make the zinc material sound more attractive. The colors can be pale grey to pale baby blue. These have stood the test of time better than their neighboring contemporary stone markers.” |

Why Zinc Headstones Still Haunt Cemeteries

Happy Halloween! Now you have an even better reason to visit a cemetery in the spooky season – to look for zinkers!

So exactly what should you be looking for? One word: obelisks.

The most commonly produced zinkers were the four-sided obelisk, because each side panel could be customized (or temporary, if family names or relationships changed). The panels were held together with simple screws and interchangeable (even if planning for eternity), and don’t underestimate their size – some zinkers are 14 feet tall.

To identify a marker as zinc, advises ColoradoCemeteries.com, the first thing to look for is the bluish-grey to dark grey color. Give a gentle tap and listen because remember, they’re hollow, and while you’re plinking, look for seams at the corners. Another “telltale” sign is screws you should find (often acorn-shaped) jutting from the corners of the inscription panels.

Why Zinkers Are So Rare

Your ghoulish graveyard stroll may take a while because most cemeteries, says Mattern, only have one or two because zinkers were made to order. “The price ranged from $2 to $5,000, depending on the design. The reason why there are so few in cemeteries is that agents did not solely sell them. If there are a dozen white bronze monuments in a cemetery, there was a local agent who sold them, which was most likely the case at Congressional Cemetery (which has four).” Like any trend, zinkers went from hot to not and their hollow bodies came to be seen as… tacky. Another contributing factor to the relative scarcity of zinkers today is that while many have inscriptions that have endured time better than marble, zinc remains a material that gets brittle with age and develops a tendency to shatter. Imagine the guilt of accidentally shattering old Uncle Bert’s obelisk? Oof.

Cemeteries Worth the Visit

But… if you are determined to explore one of the most extensive collections of zinkers of any cemetery in the country, then head to Denver’s haunted pioneer cemetery: Riverside on Brighton Boulevard. Its 77 acres are the area’s first park-like cemetery, but at night, the 136-year-old grounds have been called more restless than a resting place.

Among the zinkers here, ColoradoCemeteries.com says, “They are large box-type markers, cherubs, lambs, and crosses of zinc. The zinker collection on these grounds is the best in the world. There are more unique and excellent examples of this short-lived marker style at Riverside Cemetery than anywhere else. The military section has a pair of zinc markers topped with tall Civil War soldiers, one facing toward the main cemetery guarding the civilian dead, and the other watching over his comrades.”

The taller of the two zinc headstones was restored in 2005, and ColoradoCemeteries.com says it has one of the most unique zinc markers of all: “The soldier’s likeness was custom-built. With the face of the veteran whose grave he marks.”

At least that’s one face in a graveyard even Barbra shouldn’t be scared of.

Hint: If you’re curious, that opening scene in Night of the Living Dead was shot in Evans City, PA, evanscitycemetery.com, and no, you won’t be its first IG selfie.

This story about zinc headstones previously appeared in Rock & Gem magazine. Click here to subscribe. Story by L.A Berry.