By Thomas Farley

Mariposite? I was not familiar with it until a few years ago, when I got a call for help with ranch sitting at a horse farm in Plymouth, California. That’s in Amador County, the middle of California’s Mother Lode. My drive there would take me through the state’s south and central gold country. As a prospector, I was eager to learn about any new “ore bodies”. But mariposite turned out to be more than just another rock to run my gold detector over.

One Mineral With Various Appreciations

I soon learned that mariposite means different things to different people. To a builder, mariposite is an attractive, marblelike ornamental stone. To a lapidary, mariposite is quartz that is flecked or streaked with dark-green mica. To the rockhound, high-quality mariposite is beautiful and collectible. And of interest to everyone, mariposite may be the rock that started the California gold rush.

A Monday morning found me driving from my hometown of Las Vegas, Nevada, to Fresno, California, a journey of some 400 miles. The next day, I traveled north on state Route 99 to Merced. At that point, I headed east to Mariposa, which marks the southern end of the Mother Lode. As I drove through the oak woodland, I thought about what I had read about mariposite. I started at the beginning: What did Mariposa mean?

Mariposa is Spanish for “butterfly”. The name of the town and county go back to the naming of Mariposa Creek. There, in 1806, Padre Muñoz, traveling with the Gabriel Moraga expedition, recorded butterflies in “great multitude, especially at night and morning”. He remarked that, “One of the corporals of the expedition got one in his ear, causing him considerable annoyance and no little discomfort in its extraction.”

Later, John C. Frémont’s land grant was named Las Mariposas, and both city and county took the Anglicized spelling in 1850. A geology relation soon followed.

Distinct Versus Variety

In 1868, Benjamin Silliman Jr., a Yale chemistry professor, collected a green, micaceous material from the Josephine gold mine in Mariposa County and named it mariposite. That word represents a common name, an unofficial working title. The International Mineral Association (IMA) does not recognize mariposite as a distinct mineral. Instead, experts classify it as a variety of muscovite, which has long enjoyed mineral status. Muscovite is the most common form of mica.

Simon and Schuster’s Guide to Rocks and Minerals does not mention mariposite. Its existence is only hinted at under the muscovite variety of fuchsite. Geology of the Sierra Nevada (Mary Hill, University of California Press, Berkeley, 1975) also carries no index entry for mariposite. Its muscovite page mentions mariposite only in passing. Minerals.net, however, lists mariposite as a distinct variety of muscovite, along with five other varieties. The confusion with its name started early on.

According to Harry Rieman’s article “Mariposite” in the November 1972 Lapidary Journal, it was determined after Silliman’s findings were published that his material was the same as the previously identified fuchsite. Since a first name takes precedence, most authorities were reluctant to use Silliman’s, but the mariposite appellation has stuck hard and is now in common use.

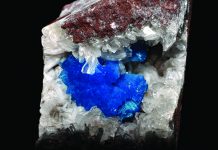

Many people apply the term “mariposite” to the rock—usually quartz—in which the green mica is found. When it occurs in rock that contains a large amount of dolomite, the rock makes for a distinctive ornamental stone. A higher percentage of quartz, on the other hand, gives mariposite rock a translucent character that is quite attractive. To sum up, you can have your mariposite in two ways: as green flecks of mica shot through a rock or as the rock itself. Yes, but what about gold?

Gold Rush Connection

Mariposite is often associated with gold. Indeed, mariposite rock sometimes has tiny inclusions of gold. As George Peabody tantalizingly put it in his August 1991 California Geology article, “Occasionally mariposite rock contains networks of gold-and iron sulfide-bearing quartz veinlets and stringers” (“Mariposite: The Rock That Made California Famous”). Sierra foothill geologist George A. Wheeldon brought even more attention to mariposite in that 1991 article. He asserted that mariposite rock was the source of gold that James Marshall found in 1848 in Coloma, on the South Fork of the American River. Wheeldon identified a 100-foot-wide mariposite outcrop four miles upstream from the old location of Marshall’s sawmill.

It is conceivable, Wheeldon concluded, that Marshall’s nugget

weathered out of the mariposite ore he located. The outcrop sits atop the Big Canyon drainage, just north of Placerville. Having extensively prospected the three forks of the American River, as well as their canyons, I was concerned. Had I passed up the opportunity to metal detect on mariposite? Did I miss it because I didn’t recognize it? I’d certainly have to learn to identify it on my trip.

About 11 miles from Mariposa, I came to the county-run Catheys Valley Park at the intersection of state Route 140) and Schoolhouse Road. It showcases one of the most elegant stone monuments you’ll ever see. Even knowing what little I did, it was apparent that this monument was constructed of the best sourced mariposite. (Monument coordinates: N 37° 26.292 W 120°05.177)

Continuing east, I passed Dials Rock and Fossil Shop—closed at the moment, but open when I returned on Friday. A Mariposa Gem & Mineral Club sign also went by. I connected with state Route 49, a.k.a. the Golden Chain Highway, at Mariposa, the beginning of the Mother Lode. Mariposa also bills itself as the gateway to Yosemite, but the California Mining and Mineral Museum is the biggest draw to rockhounds. It boasts a 13.8-pound crystalline gold specimen, discovered in 1864, called the Fricot “Nugget”. Closed on Tuesday—I would visit when I returned on Friday.

Many excellent geology guides exist for California’s Route 49. Particularly good is Roadside Geology and Mining History of the Mother Lode, by Gregg Wilkerson and David Lawler. This free pdf download covers the southern Mother Lode: Mariposa, Tuolumne and Calaveras counties (www.blm.gov/ca/pdfs/bakers?field_pdfs/field_trips/mother_lode_south/pdfs/2006_part_1_maricopa-jackson.pdf).

A Tip: I strongly recommend a navigation system for your vehicle. Especially in the middle of the Mother Lode, Route 49 is not a continuously north-south route. There are detours, abandoned sections, jogs and bypasses. A current, conventional road atlas is also a good idea. It allows you to navigate better and to let others show you where points of interest are. No one has GPS coordinates in their head; having something in hard copy lets people share landmarks and locations.

Mariposite In the Wild

Driving north through town, I saw large, green boulders occasionally lining roadways and parking lots. I wasn’t sure if they were mariposite, having not seen it in the wild. The community of Bear Valley came and went, and I soon found myself in mariposite country. Local rockhounds say all side roads should be investigated for mariposite, not just road cuts, along Route 49. That includes Bear Valley Road, Drunken Gulch Road, Schilling Road, Buckhorn Fire Road, French Road, and the Mary Harrison Mine Road. Before Route 49 drops into the Merced River Canyon, there is a terrific overlook from which to get the lay of the land. (Overlook coordinates: N37°35.293’ W120°07.467’)

After a steep decline and innumerable hairpin curves, I approached the Route 49 bridge over the Merced River. Just before it is the Lake McClure Bagby Recreation Area, known to locals simply as Bagby. You can rockhound and pan there for just a day-use fee. Ask directions to Jade Cove. (Bagby coordinates: N37° 36’ 35.1396” W120° 8’ 4.0848”)

On the north side of the river was an impressive road cut: an entire hillside composed of crumbly, quarter-size pieces of serpentinite—my old gold-detecting nemesis—glinting in the sun, showing a light green cast. I pulled over to take pictures of it. There’s so much serpentinite in the Sierra foothills that it has been used as road base in highways for decades. I found out later that mariposite, unlike serpentinite, doesn’t glisten in full sunlight; rather, it looks a faded, pale green. If you do want some serpentinite at this location, look for larger pieces on the river side of the road, just down the bank from where you’ll park your car. This is also a place to get to the river to investigate panning potential. (Road cut coordinates: N37°36.811 W120°08.390)

Mariposite’s Relations

Serpentinite is a possible host rock for gold, and it can be collected for lapidary work. Poor serpentinite flakes and is crumbly. The best serpentinite is dense, solid and lustrous. At the least, serpentinite rock indicates highly mineralized soil, which every gold prospector is looking for, even if serpentine soils represent the most miserable ground to detect on. And there’s an important relation to mariposite that I can mention here.

“Mariposite has resulted from the hydrothermal alteration of serpentine.” So wrote Adolph Knopf in “The Mother Lode System of California”, a U.S. Geological Professional Paper from 1929. Between 108 million and 127 million years ago, hot water—around 650°—upwelled from deep in the earth, mineralized with constituents like carbon, silica, quartz, potassium, and carbon dioxide. This enriched fluid broke through fissures, cracks and faults in the crustal rocks above it, whose base was frequently serpentine. When these hydrothermal fluids encountered the serpentine bedrock, a chemical reaction occurred and formed mariposite, containing deposits of quartz, chrome-mica and, metallic sulfides, including—sometimes—gold.

My drive continued toward Coulterville, about 10 miles farther on. Traffic kept me out of some road cuts; it was difficult finding a parking spot when I thought I saw something. James Mitchell’s Gem Trails of Northern California, Revised Edition (Gem Guides Book Co., 2005), stated there are things to see along this stretch, but I did not find anything promising. To be fair, I did not have time to pursue any side roads. I did know, however, where one outcrop was definitely located, and I hurried to get there. I had read about this site in many Route 49 geology road trip accounts.

At the intersection of Route 49 and Route 132 in Coulterville is the Northern Mariposa County History Center. An E Clampus Vitus monument out front is built entirely from stacked mariposite stone. One or two obvious mariposite boulders sat on the road shoulder. Maxwell Creek, across the road, did not hold any small, collectible pieces. (History Center and monument coordinates: N37°42.615’ W120°11.830’)

I then drove west on Route 132 about two-tenths of a mile to find the outcrop I had researched. I saw nothing matching my notes.

After a few more miles, I backtracked and parked across the road, where I thought the outcrop should be. There was nothing but country rock, possibly schist, looking washed out in the bright sunshine. Discouraged, I drove north on Route 49, looking for the next spot. After five or six miles, my inner rockhound told me to go back. I realized I had a photo of the location from the Internet. Geology teacher Garry Hayes considers the Coulterville outcrop a candidate for the most important geologic road cut in California. I had to find it.

In the Trenches Seeking Mariposite

Returning to where I had parked before, I compared the photo to the outcrop. A cloud moved overhead and the formerly bleached-looking rocks turned bluish-green. I put on my bright-yellow safety vest and crossed the road. This site is at the intersection of routes 132 and 164, which is Old Highway 49. Looking much more carefully at the outcrop, I could see veins of quartz coursing through the rock.

Wonderful swirls laced the stone. This was mariposite at its finest. Or more precisely, what Wilkerson and Lawler would call quartz-ankerite-mariposite rock. I wondered whether I had passed mariposite in earlier prospecting days, not noticing the rock when it was in full sun.

I thought I might easily knock out a bookend-size piece. Not so. The rock proved completely impossible to break, even with deep joints all around the stone. But as I continued to marvel at the mariposite, I felt good about not disturbing the rocks. As I was leaving, I spotted a few tiny flecks of brassy-looking material. My hand-held Falcon detector did not sound off on these spots, so I assumed they were pyrite. Also, fortunately, the mariposite presented itself as quiet ground, not fighting my detector. It would be wise, therefore, for me to look for and then carefully detect on any mariposite outcrop while in the Mother Lode. (Mariposite outcrop coordinates: N37°42.470’ W120°11.874’)

Driving north from Coulterville for about eight miles, I was unable to find the collecting spot described in Darold Henry’s California Gem Trails (©Daniel L. Gordon, 1977). He said pieces could be collected out of a streambed on the west side of Route 49, which may be Blacks Creek. It should appear before Penon Blanco Road. Check my GPS coordinates in your Web browser if you want to try to find it.

You can even view the area in Google Street View. Remember, too, what Henry ruefully said so many years ago about the foothills: “In general where the minerals lie is completely enclosed in barbed wire.” (Possible collecting site coordinates: N 37°44.1072 W 120°13.629’)

Additional Stops on the Road

Running out of daylight, I sped up to get to the horse ranch in Plymouth. I passed Jamestown, where I had wanted to visit Gold Prospecting Adventures. There was no time, either, to visit Columbia State Historic Park or Ironstone Vineyards, home to a 44-pound crystalline gold specimen, in Murphy. Perhaps I could visit these places on the way back, but the California Mining and Mineral Museum would be top priority.

After a few days of feeding horses, I left on Friday morning and headed south on Route 49. A worthwhile stop is a BLM site called Big Bar Launch. It’s just below the Route 49 bridge over the Mokelumne River, on the border of Amador and Calaveras counties. Although it’s meant for launching rafts and kayaks, it looked like a good place to pan or sluice when the water is lower in summer. A descriptive signboard there lists other BLM land upstream. (Panning site coordinates: N38°18.701’ W120°43.241’)

I then proceeded to Columbia, which I had last visited as a child. It looked the same as I remembered—indeed, it has to remain the same. It’s owned by the state of California, which has control over all the buildings. Storekeepers lease their space in vintage Gold Rush buildings. A blacksmith still hammers out a tune on a forge. It was a little slow when I visited at 10 in the morning, but everyone I talked to seemed in good spirits and relished working in so unique a surrounding.

Back in Mariposa, the California Mining and Mineral Museum houses a spectacular collection of California-related material.

Unfortunately, they no longer allow any photography of the displays inside for security reasons. I could only stare through the glass at a nice-size piece of gold-speckled mariposite ore. The staff did graciously roll out a small, foliated mariposite boulder from a back room for me to photograph. This giant doorstop would be an amazing find for any rockhound. The museum is in the Mariposa Fairgrounds at 5005 Fairgrounds Road and can be contacted at (209) 742-7625.

Shop Stop

I next stopped at the Mariposa Gem & Mineral Club Store at 4994 A 7th St. in downtown Mariposa. It’s usually open Monday through Saturday from 10 a.m. to 4 p.m., but call (209) 966-4367 to make sure. It’s an all-volunteer organization run by enthusiastic members. I bought a nice vertical mariposite slab mounted on a horizontal slab of mariposite. Besides rocks, minerals and jewelry, you can get local rockhounding advice. Cash only!

Making my way back to Merced on Route 140, I saw that Dials Rock and Fossil Shop was open. Mike, the owner, is also a miner. We discussed gold and prospecting, and it was very clear he is an expert on local geology. Using my last dollars—cash only—I purchased a hunk of mariposite. It looked like rock that was normally found in the field. Mike’s shop is at 4006 State Route 140, Catheys Valley. Call (209) 966-2127 first. (Dials Rock shop coordinates: N37°28’49.39” W120°01’36.70”)

My discussion with Mike on the mysteries and bafflements of gold prospecting got me thinking about that mariposite outcrop high above the South Fork of the American River, the possible source of James Marshall’s gold.

In 1987 a 10,500-pound boulder from that outcrop was donated for use in the Fountain of Freedom Monument, to be built in Philadelphia. The monument would mark the 200th anniversary of the U.S. Constitution and the Bill of Rights. Amid much fanfare and expense, large rocks from all over the country made their way to Pennsylvania, including picture sandstone from Utah, travertine from Montana, and granite from North Dakota.

So can you go visit that mottled green-and-white mariposite boulder, possibly bearing gold? Alas, no. The epilogue to Peabody’s article describing the project reads simply, “The monument was never constructed and the location of the stones is unknown” (“Mariposite: The Rock That Made California Famous”, How About That!, El Dorado County Historical Society, 1991).

Thomas Farley is a freelance writer and rockhound living in Las Vegas.