By Steve Voynick

After the ores played out, the fortunes of the West’s legion of frontier-era mining camps diverged. Most became ghost towns, while those that survived through various forms of economic transition did so at the expense of their mining heritage. An exception among the survivors is the legendary silver-mining boomtown of Creede, Colorado.

Although Creede’s last producing mine closed 35 years ago, its mining and mineral heritage is alive and well today. Along with a rollicking history and spectacular mountain setting, Creede’s attractions include a historic mining district with an underground-mine tour and an underground mining museum, collecting sites, the main street lined with Victorian-era architecture, and specimens of unusually beautiful metal ore. Combine all this with mine-drilling contests and an underground rock-and-mineral show, and this old silver camp becomes an ideal destination for rock hounds, mineral collectors, lapidaries, and mining-history buffs.

Creede is perched at the lofty elevation of 8,850 feet in southwest Colorado’s San Juan Mountains, a relatively young range of 14,000-foot-high peaks that formed well after the Laramide Orogeny had uplifted the Rocky Mountains 65 million years ago. Following the Laramide uplift, magma accumulated beneath what is now southwestern Colorado, “doming” the entire region upward. About 40 million years ago, after the eroded dome could no longer contain the underlying magma, a lengthy period of intense volcanism built the San Juan Mountains.

Creede is perched at the lofty elevation of 8,850 feet in southwest Colorado’s San Juan Mountains, a relatively young range of 14,000-foot-high peaks that formed well after the Laramide Orogeny had uplifted the Rocky Mountains 65 million years ago. Following the Laramide uplift, magma accumulated beneath what is now southwestern Colorado, “doming” the entire region upward. About 40 million years ago, after the eroded dome could no longer contain the underlying magma, a lengthy period of intense volcanism built the San Juan Mountains.

Some 26 million years ago, a small volcano exploded near the present site of Creede, then subsided to form a caldera, or collapsed volcanic system. As the surrounding rhyolite country rock fractured, hydrothermal solutions rich in silica, silver, lead, and zinc surged upward. In the decreased temperatures and pressures nearer to the surface, these solutions solidified into massive veins of chalcedony, banded agate, amethystine quartz, native silver, and the sulfides of silver, lead, and zinc. Erosion later sculpted the area to its present topography and exposed the mineralized veins.

In August 1889, prospector Nicholas Creede discovered an outcrop of amethystine quartz and native silver. Other prospectors found linear trends of similar outcrops that indicated large, continuous vein systems. After tracing the largest vein on the surface for more than two miles, they named it the Amethyst Vein after its primary component—distinctive, lavender-colored quartz.

While miners were sinking shafts and driving tunnels into the rhyolite to reach the Amethyst Vein, they also erected a string of ramshackle cabins along the floor of West Willow Creek Canyon. This rapidly growing camp soon consolidated into a town near the spacious mouth of the canyon that was named Creede in honor of Nicholas Creede.

In 1891, the first year of production, Creede’s mines yielded 380,000 troy ounces of  silver from shallow ores that sometimes graded one thousand troy ounces of silver per ton. Within two years, annual silver production had topped 4.8 million troy ounces and Creede, with a population of 10,000, had become the biggest name in western silver mining. But by then, the nation was already awash in silver. Through the 1880s, hundreds of mines, mainly in Colorado and Idaho, had contributed to a silver glut. In 1891, western legislators saw the writing on the wall and pressured Congress to support the metal’s price by passing the Sherman Silver Purchase Act.

silver from shallow ores that sometimes graded one thousand troy ounces of silver per ton. Within two years, annual silver production had topped 4.8 million troy ounces and Creede, with a population of 10,000, had become the biggest name in western silver mining. But by then, the nation was already awash in silver. Through the 1880s, hundreds of mines, mainly in Colorado and Idaho, had contributed to a silver glut. In 1891, western legislators saw the writing on the wall and pressured Congress to support the metal’s price by passing the Sherman Silver Purchase Act.

After a bitter political battle, Congress repealed this act in 1893. When the federal treasury stopped buying silver, the price of the metal plummeted, mines closed in droves, and dozens of silver camps went from boom to bust literally overnight. Only Creede escaped the silver crash relatively unscathed. With its large reserves of high-grade ore, it could still mine silver profitably, even at severely depressed prices for the metal.

The Creede Mining District also has four other vein systems: the OH, Bulldog, Alpha-Corsair, and Holy Moses. The ores in these veins consisted mostly of non-mineralized, massive, white quartz interspersed with layers of heavily mineralized, dark quartz, the latter rich in acanthite, argentiferous galena, silver sulfide, and native silver. Although these veins yielded substantial amounts of silver, none could challenge the size, extent, and overall richness of the Amethyst Vein.

Creede’s largest mine was the Commodore at the southern end of the Amethyst Vein. By 1912, its 200 miles of underground workings and five levels as deep as 1,500 feet had yielded 16 million troy ounces (549 tons) of silver, 1,700 tons of lead, and lesser amounts of zinc. Over its first 20 years, the Commodore’s ore had averaged an astounding 45 troy ounces of silver per ton.

The Amethyst Vein continued to yield silver until the Commodore, the last of the district’s original mines, shut down in 1976. By then, the Homestake Mining Company had developed the nearby Bulldog Mine, which produced until 1985 and was the district’s last operating mine. Over a period of 94 years, Creede’s total production topped 60 million troy ounces (more than 2,000 tons) of silver, 9,000 tons of lead, and 4,000 tons of zinc.

The Amethyst Vein continued to yield silver until the Commodore, the last of the district’s original mines, shut down in 1976. By then, the Homestake Mining Company had developed the nearby Bulldog Mine, which produced until 1985 and was the district’s last operating mine. Over a period of 94 years, Creede’s total production topped 60 million troy ounces (more than 2,000 tons) of silver, 9,000 tons of lead, and 4,000 tons of zinc.

The three-mile-long Amethyst Vein has a well-defined, concentric, geodic structure with crystals and masses of argentiferous galena (silver-bearing lead sulfide), sphalerite (zinc sulfide), acanthite (silver sulfide), and native silver scattered throughout. Its outer zone consists of dark, massive quartz, rich in argentiferous galena and sphalerite. Then come banded layers of white and bluish chalcedony, masses of dark, mineralized quartz, and a zone of translucent amethystine quartz, in which traces of manganese create attractive pink, violet, and lavender hues.

Intergrown combs of white quartz crystals surround the center of the vein, which, space permitting, contains growths of colorless, drusy quartz crystals. In some places, the center is filled with “center ore”—solid masses of acanthite, argentiferous galena, and native silver, which, during Creede’s boom days, graded several thousand troy ounces of silver per ton.

Miners weren’t the only ones who appreciated the beauty of Amethyst Vein ore. By 1894, lapidaries had begun slabbing and polishing the ore to sell as souvenirs and curios and to serve as panels for Tiffany-style lamps.

After its mines finally closed, Creede survived on revenues generated by growing  numbers of tourists attracted by outdoor-recreation opportunities, open space, and mountain scenery. Today, Creede, population 350, is the seat of Mineral County, an 878-square-mile tract of forests, meadows, and rugged mountains with just 1,000 full-time residents.

numbers of tourists attracted by outdoor-recreation opportunities, open space, and mountain scenery. Today, Creede, population 350, is the seat of Mineral County, an 878-square-mile tract of forests, meadows, and rugged mountains with just 1,000 full-time residents.

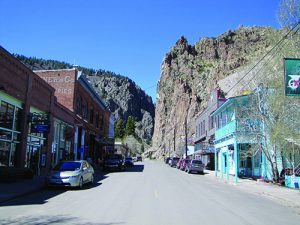

First-time Creede visitors are immediately drawn to the spire-like, sheer-walled, rhyolite cliffs that soar 1,000 feet above the end of Main Street. The historic mining district extends seven miles to the north and is accessed by the 17-mile-long Bachelor Historic Tour loop drive. From Main Street, the loop leads into Willow Creek Canyon and the first point of interest—the Creede Underground Mining Museum and Community Center.

In 1990, the town hired three miners who had previously worked at the Bulldog Mine to drive 600 feet of drifts within a rhyolite cliff. This maze of tunnels would house a Community Center, a firehouse, and an Underground Mining Museum.

Since opening in 1992, the Creede Underground Mining Museum has hosted more than 20,000 visitors. It features two dozen elaborate, life-sized exhibits explaining such aspects of frontier-era and modern mining operations as drilling, blasting, explosives preparation, timbering, assaying, and ore haulage. The underground museum also has self-guided tours, summertime guided tours, mining videos, displays of native silver and Amethyst Vein ore.

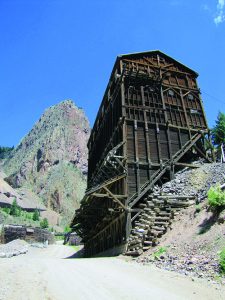

Continuing north through West Willow Creek Canyon, the Bachelor Historic Tour loop passes beneath the Commodore Mine’s ore bin. Perched on a steep slope, this massive bin with its elaborate cribbing and weathered timbers is among Colorado’s most-photographed historic mine structures.

Despite several narrow sections and steep grades, the loop drive is suitable for passenger vehicles. It passes many points of interest marked with interpretive signs, including the sites of the Captive Inca, Amethyst, Park Regent, Equity, Holy Moses, and Last Chance mines. The steep terrain throughout the mining district is often at the limit of geological competence, and the loose rock is dangerous. These mines and their dumps are posted both as private property and for safety reasons.

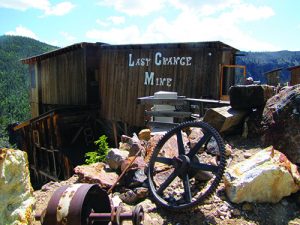

The big exception is the Last Chance Mine. Located on the “backside” of the loop high above West Willow Creek Canyon, the Last Chance welcomes visitors. Developed in 1891 at the north end of the Amethyst Vein, it was one of Creede’s richest mines and operated continuously until 1947. It was finally sealed shut in 1974.

In 1997, Jack Morris, a long-distance trucker from Missouri with an interest in minerals and mining history, purchased the Last Chance. Morris has since turned the old mine into a major attraction, first opening the mine dump to mineral collectors, then investing a decade of work and considerable expense to reopen sections of the mine itself for state-approved underground tours. Today, visitors enjoy a 40-minute, quarter-mile-long, well-lighted, guided tour past ore chutes, towering stopes with their original timbers, and mine walls that in places gleam with blue-and-purple Amethyst Vein exposures.

An observation deck overlooks West Willow Creek Canyon 800 feet below, while a timber walkway accesses the mine dump, which is filled with Amethyst Vein material ranging in sizes from tumbling pieces to cabinet-sized specimens and even larger ornamental blocks. The Last Chance dump has also yielded one-inch-long amethyst crystals; multicolored “ametrine” crystals of purple amethyst and yellow citrine; and specimens of argentiferous galena, acanthite, and blue-green copper minerals.

Collectors are provided with buckets, rock hammers, and water bottles, the latter to spray dump material to reveal the distinctive Amethyst Vein banding patterns. Exploring the dump is free; material may be removed for a charge of two dollars per pound. Morris also sells specimens from his extensive personal mineral collection.

The Last Chance Mine remains a work in progress. Morris opens new sections of the mine each year and is designing special tours for gem-and-mineral club members, geology students, and professional geological-association members. He is also designating specific underground areas where collectors will be able to “mine” their own Amethyst Vein specimens from in situ veinlets.

While Morris was reopening the Last Chance Mine in the early 2000s, jewelry-maker Jenny Inge, owner of Rare Things Gallery of Treasures on Creede’s historic Main Street, was developing another attraction. Inge, who had learned jewelry-making in her home state of Texas, first visited Creede on a motorcycle trip in 1972. Drawn by the town’s rugged mountains, free spirit, and colorful history, she settled there in 1974. Her Rare Things Gallery of Treasures is now one of Creede’s most popular galleries, widely acclaimed for its custom-made jewelry, works of art, and mineral and fossil.

Inge also envisioned Creede, with its rich history, unusual geology, and remarkable scenery, as a made-to-order setting for an annual rock-and-mineral show. And the perfect venue had just then been completed—the Underground Mining Museum.

Inge also envisioned Creede, with its rich history, unusual geology, and remarkable scenery, as a made-to-order setting for an annual rock-and-mineral show. And the perfect venue had just then been completed—the Underground Mining Museum.

Although the first Creede Rock & Mineral Show in 2001 was a humble affair, both buyers and dealers loved it, and it grew steadily. Today, this annual summer event, which attracts 45 dealers and more than 1,500 visitors, features educational displays, evening lectures, and specimens from around the world including, of course, rough and polished specimens of Amethyst Vein ore.

Having outgrown the underground, the show now spills out of the portals and onto the floor of Willow Creek Canyon. As of the publication of this issue of Rock & Gem, the 2020 Creede Rock & Mineral Show is scheduled for July 31st to August 2nd, during which it will celebrate its 15th year.

Creede also celebrates its heritage with annual mine-drilling contests. Frontier-era miners were experts at hand-drilling—drilling blast holes in solid rock by manually hammering chisel-like steels. Although an exhausting and dangerous form of manual labor, hand-drilling was also a skill that demanded perfect coordination, boundless stamina, and unerring accuracy in the use of the heavy hammers.

In “single-jacking,” a miner held the steel in one hand and swung a four-pound sledgehammer with the other. “Double-jacking” was considerably faster but required a team of two miners: a “shaker,” who gripped the steel with both hands, and a “hammer man” who rhythmically pounded the steel with an eight-pound sledge.

Early miners at Creede and other mining camps took great pride in their drilling skills, which they demonstrated at public drilling competitions. Today’s drilling contests are part of Creede’s annual “Days of ‘92” festival. Held during the July 4th holiday, the Creede contests are a regular stop on a circuit of 18 professional-level, mine-drilling contests in eight western states, all having standardized rules and big cash prizes. Audiences have the unusual opportunity to watch and photograph miners as they race the clock to drill holes in solid granite using both frontier-era hammers and hand steels, and modern pneumatic rock drills.

Creede’s Main Street is a showcase of colorful, well-preserved Victorian-era architecture. The Creede Museum, housed in the town’s 127-year-old railroad depot, is packed with exhibits of frontier-era tools and utensils, historical photographs and newspapers, hand-drawn fire wagons and horse-drawn hearses, gambling paraphernalia, and many other items that depict life as it was during Creede’s silver-boom years.

Along with a dozen art galleries, another cultural attraction is the renowned Creede Repertory Theatre, a professional theater company that features nationally acclaimed actors now in its 64th year of presenting summertime musical events and stage productions. Fossil collecting is popular at several nearby sites. In the mid-Tertiary Period time 26 million years ago, when the Creede area was mineralized, the area was the site of a lake with dense, shoreline vegetation. The fine volcanic ash that periodically filled the lake was an excellent fossil-preservation medium. Today, finely detailed fossils can be found in exposures of crumbly strata of buff-to-yellowish mudstone, shale, and tuff.

At the Wheeler Geologic Area southeast of Creede, erosion has sculpted a massive tuff formation into a bizarre badland topography of brightly colored pinnacles, spires, slump blocks, and balanced “cap rocks.” This area was granted protective status as Wheeler Geologic National Monument in 1908, a designation that was later rescinded because of its remoteness and inaccessibility. Even today, the Wheeler Geologic Area can be reached only by high-clearance, four-wheel-drive vehicles, or a 14-mile-long, round-trip hike.

Because of Creede’s high elevation and lengthy winter, the best time to visit is from late spring through early fall. Creede is located off the beaten path on Colorado Route 149. It is 21 miles north of the town of South Fork and U.S. Highway 160, southern Colorado’s main east-west highway.

For More Information

Visit the Creede/Mineral County Visitor Center and Chamber of Commerce website at www.creede.com. For information about the Last Chance Mine, visit www.lastchancemine.com; for the Creede Rock & Mineral Show, visit www.creederocks.com. The Creede Visitor Center on Main Street provides maps of the Bachelor Historic Tour loop drive, fossil-collecting sites, the Wheeler Geologic Area, and many other points of interest in and around Creede—a frontier-era survivor that has remained true to its mining and mineral heritage.