Neptunite, along with natrolite and benitoite, is one of California’s most striking minerals. When I mentioned these patriotic minerals to a friend, he looked puzzled. “Where’s the red?” he asked. Well, let me explain…

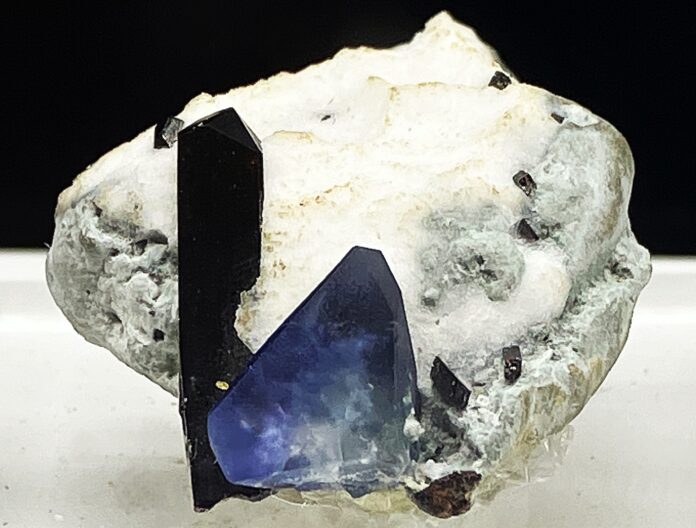

Benitoite Crystals on Natrolite: A Stunning Contrast

The story of benitoite may be familiar to many collectors. This rare blue barium titanium silicate, California’s official state gemstone since 1985, is found in only a single region at the headwaters of the San Benito River. Even there, it’s not easy to find. First discovered in 1907 by prospector James Marshall Couch and formally described in 1909 by Berkeley professor George Davis Louderback, benitoite has been mined on and off for more than a century. What caught Couch’s eye that morning wasn’t just the sparkling blue crystals—it was the white bed of natrolite that surrounded them, a striking backdrop that highlights benitoite’s brilliance.

Neptunite, named for the Roman god of the sea, was first found in association with a similar mineral called aegerine, named for the Norse god of the sea.

Benitoite’s Unique Form and Natrolite Matrix

Benitoite has a unique form. In the 1800s, mineralogists made a table of all possible crystal shapes, but one spot was vacant, a spot for a ditrigonal-dipyramidal form, which looks like two low, three-faced pyramids stuck together at the base, with all the tips flattened. Nothing to match it had been found—until benitoite. Exceptional rarity makes crystals primarily high-priced collectibles, but they are also faceted for jewelry. Even though it’s at the soft end of the hardness scale for gemstones (Mohs scale of hardness 6-6.5), it cuts into stunning stones more refractive, or sparkly, than diamonds. And far more rare.

Benitoite is sometimes called the “California blue diamond.” In fact, stumbling across benitoite, Couch thought he had discovered blue diamonds or sapphires while grub-staked by Coalinga businessman Roderick W. Dallas to seek mercury ore. It’s said that in the morning light, his eye was attracted by a white patch in the rocks. On close inspection, he found the white to be peppered with blue crystals, with still more blue crystals littering the surrounding ground.

Natrolite: The Snow-White Matrix

That white patch enveloping the benitoite proved to be natrolite. Sometimes called “needle zeolite,” natrolite, or hydrated sodium aluminum silicate, forms acicular crystals clustered in radiating sprays. Larger crystals take the form of long, squared prisms capped by low pyramids. But at the benitoite locality, natrolite grew as a compact fibrous mass filling voids and cracks in blueschist and enveloping associated minerals like benitoite. It’s often dissolved away in hydrochloric or muriatic acid, which gelatinizes the natrolite, to expose the gemstone crystals.

With pieces intended for the specimen market, care is taken during acid etching to preserve some natrolite, providing a contrasting snow-white background to highlight the blue benitoite. Compared to rare benitoite, natrolite is fairly abundant around the world and has important industrial uses as a natural chemical filter and has been used as a water softener and for treating industrial wastewater containing cyanides and heavy metals.

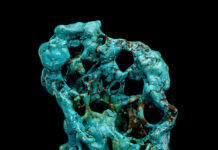

Neptunite: California’s Overlooked Black Mineral

Often nestled together with benitoite in that white natrolite bed is opaque but shiny, jet-black neptunite. Its well-formed prismatic rod-like crystals are square in cross-section with pointed terminations. In form and luster, neptunite crystals from the California locality are the best in the world, and the combination of benitoite and neptunite on natrolite makes for very showy display specimens that command attention among collectors.

However, compared to benitoite, neptunite seems to be the Rodney Dangerfield of the mineral world: it don’t get no respect! Indeed, Couch apparently didn’t even mention it in announcing his benitoite discovery. Bob Jones did a lot of research about that discovery, including Couch’s own writings, and he reported, curiously, “I find no mention of the lovely black neptunite crystals that had to be present in the white natrolite of Couch’s find. Indeed, that snow-white rock that attracted Couch had to have loose crystals of this black complex mineral scattered about right there with the blue benitoite.”

Neptunite Collectors and Market Value

Today, while you may have to pay $300 or more for a tiny, poor-quality thumbnail benitoite and as much as a whopping $35,000 for a big, showy cluster on matrix, a quick online search yields small neptunite crystals going for $35 to $50, and even lovely large clusters commanding just $150 to $275. Recently, I did spot a not very remarkable one-inch specimen listed on eBay for $600 “or best offer,” but that seems to be the exception. Most neptunite is priced at what I’d call the mid-range market.

Be that as it may, some folks do prove partial to benitoite’s neglected cousin. A friend of mine, Susan Harlow, has a superb collection of minerals from the California benitoite locality. They were personally collected by her father, Art Pawson, during a 1937 excursion with none other than legendary figures Edward Swoboda and Peter Bancroft when they were all in their early 20s. Per Susie, while Ed and Pete had benitoite in their crosshairs, Art (who would become a student of George Louderback at Berkeley) was actually more interested in collecting the neptunite. On his passing, he left his daughter with many fine specimens she graciously allowed me to photograph.

Neptunite Chemistry and Crystal Form

Neptunite is chemically complex, so hold your breath: it’s a potassium, sodium, lithium, iron, manganese, titanium silicate, or KNa2Li(Fe2+,Mn2+)2Ti2Si8O24. Although fairly rare itself, it’s not nearly as rare as benitoite and has been found in several other localities, which perhaps accounts for the lower market value. Along with benitoite and natrolite, at the California locality, it formed in blueschist under high-pressure conditions in hydrothermal veins altered by high-temperature fluids.

Neptunite’s rod-like crystals are usually sharp-edged and smooth and can grow to a length of nearly three inches, but even two inches is considered long for neptunite. Most individual crystals I’ve seen are an inch or less, more in the realm of thumbnail specimens. While most often seen as individual rods that may be doubly terminated, neptunite also exhibits interpenetration twinning, forming a sort of Saint Andrew’s cross.

As is evident by its chemical formula, neptunite holds iron and manganese—the (Fe2+, Mn2+) in the formula—in varying proportions. Thus, rather than a single discrete mineral, it forms as a series. California neptunite resides as the iron end member of the series, whereas neptunite with a high manganese content is called manganoneptunite. This manganese end member is typical of localities at Mont Saint-Hilaire in Quebec, Canada, and on Russia’s Kola Peninsula. However, to the naked eye, there’s very little difference between these two end members of the neptunite group.

Neptunite’s Discovery and Naming History

Neptunite was first described not so long before benitoite in 1893 by Swedish mineralogist Gustav Flink from specimens found in association with aegirine in Narsârssuk, Greenland. Aegirine was named in 1834 by Norwegian priest and mineralogist Hans Morten Thrane Esmark, then formally described in 1835 by Jöns Jacob Berzelius for specimens found in Norway.

It was named after the Norse Sea god Ægir, so I suppose when a similar mineral was found alongside it, it made sense to name that new mineral after the Roman god of the sea, Neptune. Those gods like to stick together, after all. It has since been found in California, Quebec, Mongolia, Tajikistan, Ireland, Russia, Slovakia, Namibia, Australia and elsewhere around the globe.

Uses and Collecting Tips for Neptunite

Neptunite is piezoelectric. In other words, it generates an electric charge in response to mechanical stress and pressure. Only some 2% of the nearly 5,000 known mineral species exhibit this effect, with quartz being perhaps the best-known example. Piezoelectric quartz has many practical and industrial uses, from ultrasound transducers to frequency meters and signal generators and in sensors to detect pressure and vibrations, including engine knock sensors.

Ever the Rodney Dangerfield of the mineral world, neptunite has not enjoyed similar industrial respect owing to its relative rarity and the ready availability of manmade composites and abundant natural alternatives like quartz. For these reasons, the piezoelectric properties and potentials of neptunite have not even been well studied. So, if you’re a grad student seeking a Ph.D. thesis, have at it!

Despite a high glossy shine, neptunite crystals are rarely even used as faceted gemstones for jewelry due to opacity, brittleness, and relative softness (Mohs 5-6). Still, some small crystals have been faceted. The largest known faceted specimen is 11.78 ct. It was identified by the Gemological Institute of America, which shows a photo of it on their website. Still, faceted neptunite gems are extremely rare, and the mineral is most commonly sold simply as a collector specimen. What can you do with neptunite? Buy it!

Revealing Neptunite’s Hidden Red

While neptunite crystals may look black, their true color shines through in just the right viewing conditions. Move a bright light around as you closely examine the thin edges of particularly gemmy crystals, and you should soon see it: a deep blood-red color glowing through. It’s even more noticeable in thin fragments or splinters. A brownish-red hue is also evident in some broken and/or worn specimens. That black appearance? It’s due to neptunite’s opacity. It takes a bit of effort, but you can make that red emerge. Providing further evidence of its true color, neptunite produces a reddish or cinnamon-brown streak on an unglazed ceramic streak plate.

Collecting Neptunite, Natrolite, and Benitoite

You can collect your own neptunite at the California State Gem Mine near Coalinga, California. In 2005, Dave Schreiner obtained the claim to the classic Benitoite Mine. In addition to the mine, he purchased Old Road Camp, a historic work camp of Depression Era buildings and dormitories. Within this camp, Dave provides the opportunity to screen for your very own neptunite, natrolite and benitoite from material he’s hauled in from the mine dumps. I visited in 2010 and found a twinned crystal. A bit weathered and rough, it showed nice form, nonetheless, complete with a reddish hue. If you’d like to try your hand, check out the Benitoite Mining Company.

Frequently Asked Questions

1. What is neptunite and where is it found?

Neptunite is a rare black mineral with red highlights in thin edges. It forms in California’s benitoite locality and has also been found in Quebec, Russia, Mongolia, and a few other sites worldwide.

2. Why does neptunite look black but sometimes appear red?

Neptunite appears black due to its opacity, but in bright light or thin edges, a deep red or cinnamon-brown color shines through, revealing its hidden hue.

3. How rare is benitoite and why is it so valuable?

Benitoite is extremely rare, found in only one California region. Its unique crystal form and vibrant blue color make it highly prized for collectors and jewelry, sometimes earning prices of tens of thousands of dollars.

4. What is natrolite and why is it important in mineral specimens?

Natrolite is a white, fibrous zeolite mineral that often forms the matrix for benitoite and neptunite. It provides visual contrast, making specimens display-ready, and has industrial uses like water softening and chemical filtration.

5. Can neptunite or benitoite be used as gemstones?

Yes, benitoite is occasionally faceted into jewelry despite a Mohs hardness of 6–6.5. Neptunite is rarely cut due to opacity and brittleness, but small faceted gems do exist for collectors.

6. Where can I collect neptunite, benitoite, and natrolite?

Collectors can find all three at the California State Gem Mine near Coalinga, California, or in old tailings from the Benitoite Mining Company. Always check local regulations before collecting.

7. How should I care for neptunite or benitoite specimens?

Store them away from heat and direct sunlight. Avoid harsh chemicals; clean gently with soft brushes or water. Faceted stones should be handled carefully due to their relative softness and brittleness.

Neptunite, Natrolite, and Benitoite: California’s Patriotic Minerals

Taken together, neptunite, benitoite and natrolite provide for aesthetically dramatic display specimens with fine contrast; a lovely, rare suite from the state of California. Now that you know, take time to appreciate the true red in the black, white and blue!

This story about benitoite appeared in Rock & Gem magazine. Click here to subscribe. Story and photos by Jim Brace-Thompson.