Native American jewelry is something first-time travelers visiting the American Southwest are often awed by in terms of availability and sheer abundance of beautiful turquoise-in-silver jewelry. Commonly known as “Indian jewelry,” this style is so deeply ingrained into the regional culture that it might seem to be an ancient tradition. But turquoise-in-silver jewelry only originated only in the 1880s through an unlikely combination of cultural, economic and technical influences.

The Beginning of Native American Jewelry Making

Mexican blacksmiths first taught Native Americans the rudiments of ironworking in the 1840s. Navajos later applied these skills to easily workable silver, fashioning such ornaments as pendants, bracelets, necklaces, and disks called “conchos”—named after the Spanish concha, or “shell”—for decorating belts and hatbands.

By the 1870s, silver-working skills had spread to the Hopis and Pueblos, but only a minor craft that served limited tribal markets. But change came rapidly in 1881 when a transcontinental railroad built across northern Arizona and New Mexico carried growing numbers of passengers who were intrigued by “Indian” silver jewelry as the perfect souvenir of their travels. The jewelry market that soon developed offered a rare economic opportunity for Native American jewelry makers who had recently been confined to reservations. To enhance the appeal of their silver work they complemented it with what had been the region’s premier gemstone for some 2,000 years—turquoise.

Courtesy Steve Voynick

The Turquoise

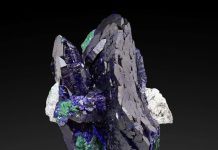

Turquoise’s ritualistic and economic value had evolved in Mesoamerica and spread northward to eventually reach the American Southwest around 200 B.C. The availability of turquoise increased rapidly after 850 C.E., when Ancestral Puebloans began large-scale mining at Cerrillos near present-day Santa Fe, New Mexico, and the Chaco Canyon culture became the leading source of worked turquoise and the hub of a high-volume turquoise trade. Turquoise mining would later decline sharply at Cerillos and other sites after Spanish and Anglo settlement destabilized Native American societies.

The establishment of the railroad passenger market for turquoise-in-silver jewelry gave Native Americans good reason to reopen many old turquoise mines. Top-quality turquoise, however, with its saturated blue and blue-green colors that so attracted the interest (and money) of railroad passengers, was never abundant. What was plentiful was “chalk” turquoise, which had only minimal value or appeal with its drab pale-blue or grayish-blue colors. But then Native American jewelry makers made a fortuitous discovery: The inexpensive blue aniline dye sold at trading posts to Native American women for dying wool yarn could also color the porous “chalk” material, thus assuring a bountiful supply of now intensely colored and easily marketed turquoise.

Courtesy Steve Voynick

The Silver

Contrary to an enduring myth, indigenous southwestern cultures did not mine silver. Their supply came almost entirely from melting down or hammering United States silver coinage—dimes, quarters, half-dollars and, most importantly, the popular Morgan dollars that were minted in huge numbers and circulated mainly in the West.

While most silver coins were completely melted and recast, others, usually dimes and quarters, were simply hammered in concave molds into cup-shaped forms which, when soldered together, made hollow silver beads perfect for stringing into necklaces. In many cases, the original stamp features—dates, script, and images—of the coins remained visible.

By 1890, the voluminous transformation of silver coinage into “Indian jewelry” had become a leading factor in the federal Treasury’s move to criminalize the defacing of U. S. coinage. Native silversmiths responded by simply switching to Mexican pesos which, with their slightly higher silver content, were actually more workable than their U. S. counterparts. Interestingly, Mexico later banned the defacing of its silver coinage and restricted its flow into the American Southwest. But by then, Native American jewelry makers were relying on commercially obtainable sterling-silver ribbons, wire and sheets.

The Legacy of Native American Jewelry

Before the appearance of “Indian jewelry,” turquoise had little value as a gemstone in the United States. Based on surveys compiled in 1881, George Frederick Kunz, a United States Geological Survey agent and gemologist for the prestigious New York City jewelry firm of Tiffany & Co., disparaged turquoise by reporting “. . . all American turquoise is sold either to tourists or collectors or to the jewelry trade only as oddities.”

But by 1890, after Tiffany itself had acquired an interest in a New Mexico turquoise mine and was successfully marketing “Indian jewelry” in the East, Kunz was singing a different tune. He now reported that turquoise “. . . of fine quality and gem value has been found in the United States” and noted that the Cerillos mines alone were annually producing turquoise valued in excess of $175,000 ($5 million in today’s dollars).

By 1900, both the image and the future of turquoise jewelry had become firmly established: As the Southwest’s iconic gemstone, turquoise, often color-enhanced, would henceforth be set in silver mounts of “Indian” design.

With the post-World War II boom in automobile tourism, demand for “Indian jewelry” skyrocketed. Fashioning turquoise-in-silver jewelry remains an important part of the Navajo, Hopi and Pueblo economies. An estimated 95 percent of the turquoise now available in the United States each year is used to manufacture “Indian jewelry.”

“Indian jewelry” originated through the unlikely combination of traditional Native American reverence for turquoise, Mexican blacksmithing skills, construction of a railroad, melted-down Morgan silver dollars, and even a bit of aniline dye. Today, bolstered by renewed interest in, and appreciation for, Native American culture, turquoise-in-silver remains an enormously popular and internationally recognized jewelry style.

This story about Native American jewelry (turquoise-in-silver) previously appeared in Rock & Gem magazine. Click here to subscribe. Story by Steve Voynick.