By Stuart “Tate” Wilson

Jim and Jennifer Sahli, owners of the Wild Turkey Mine, are a true American success story. Everything from the rich local mining history to their current involvement in producing a fantastic new semi-precious lapidary gem material makes this a great addition to the history books.

In 2018, I made the trip to the Colville River Valley of eastern Washington to interview the Sahlis. I was able to see first-hand the local geology, which produces the loveliest glowing green serpentine while spending the day mining with this couple. I also learned what it takes for this gem to make it from mine to market.

Show Connection

I met this couple more than eight years ago at a small gem and mineral show in western Washington. We were neighboring vendors, and it was one of the first shows they had attended. I was doing business as “Washington Treasures” and they as “Washington Rocks!” Naturally, we hit it off. We both shared the passion for digging Washington state material. Over the years, we’ve watched one another grow and discover amazing material. I’ve also had the opportunity to see these wonderful folks turn a passionate hobby into a profitable and enjoyable business.

While the Sahlis owe most of their success to a ton of hard work and a fair bit of luck, it is also important to realize and acknowledge the rich mining history of this area and more than a century’s worth of labor, done by those whose memories and artifacts are all that remain. If it were not for all of the work laid out by those of the past, we would not know about or have access to these localities now.

Humble Beginnings

Part of this story began more than one hundred years ago. In Europe, pre-war tensions were causing strain on international commerce. Before World War I, we sourced magnesite from Austria-Hungary and some from Greece. However, this ended as the war began. The United States government put out a call to geologists around the country, to check their records and resources to find where all domestic magnesite deposits were located. The government needed the magnesite to create the lining of an open-hearth furnace. This style of furnace was necessary for creating the steel that was not only necessary for the country’s participation in both World War I and World War II, but the industrial revolution as well.

The U.S. governments’ call was answered quickly, and among those who answered the call was R.S. Talbot. While mining dolomite to be used in his paper mill operation, test results revealed the presence of high magnesite content. Talbot switched efforts from producing paper products to mining operations and thus, marking the beginning of the “magnesite rush” in Stevens County. Additional people also responded to the call, and quickly patented mines sprung up. This boom created an industry where there once was none. Roads were built going up into the mountains, and many mines were created. Today these roads and mines remain, and in many instances, their mineral wealth and history are well documented. Simply put, the path was paved for Jim and Jennifer to start where others left off long ago.

The path in this story is both figurative and literal, as it led this couple to a particular mine that ran into a large serpentine sill of semi-precious material, which is now known as noble serpentine. The deposit was, more or less, unused since the early ’60s. During that time, the material had gone unnoticed by most, except for members of the local rock club who used it as lapidary stone.

It was during one of the local rock club meetings where the Sahlis became acquainted with this beautiful green stone. While the couple resides most of the year in western Washington, they have a summer lake home near Chewelah, located in the northeastern region of Washington. It was during a summer spent at the lake home that they hooked up with some local rock club members who shared information about local collecting sites. One of the sites happened to be the abandoned mine accessing the serpentine sill. At this point, this rockhounding couple saw an opportunity to possibly explore a new-to-them dig site.

Enchanted By Noble Serpentine

If the idea of ‘love at first sight’ extends to rockhounding, then that’s exactly what

happened to the Sahlis. They quickly recognized the beautiful noble serpentine as an exciting and widely unrecognized semi-precious gem material with market appeal. At first, they collected small amounts here and there for tumbling material and yard rock. The softness of the stone made it wonderful for tumbling, and it came out shiny and beautiful. The tumbles they produced were given as gifts to family and friends, and the response was great. Everyone loved this glowing lime-green stone.

Next, the couple sold noble serpentine at occasional gem and mineral shows in the region, as well as the Quartzsite Improvement Association Pow Wow Gem & Mineral Show. It was during the Quartzsite event they realized how much interest there was in noble serpentine. Each year they participated in the show, they would sell out of the material before the show concluded.

Unfortunately, at the same time market interest for noble serpentine was rising, access to the deposit closed, and any small production came to an end. The Sahlis had foreseen this happening and wisely tried contacting the landowners to lease or buy the land. However, their attempts were futile. The owners of the land lived across the country and did not respond to any of the Sahlis requests. The couple’s dream of opening a mine, and seeing its full potential come to fruition was starting to dissipate quickly.

Then out of nowhere, not even six months after land access ended, they received a call from the out-of-state landowners who had heard they were being summoned. The Sahlis gave a huge sigh of relief when they learned the owners were more than happy to sell the property to them and at an unbeatable price. Their dreams of owning the mine were back on track and in a better way than ever. Their minds were once again able to run wild with ideas of how they could turn mining for noble serpentine into something that could support them fully while providing the gem and mineral world with a fantastic new stone.

Starting Anew

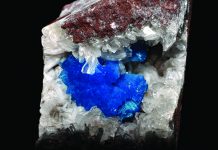

As the new owners of the property, the Sahlis decided to name it Wild Turkey Mine, because of the wild turkey flocks that frequent the area. The serpentine that occurs here is quite interesting. It has so many varieties of colors and qualities. Serpentine is a general term for a group of rocks that tend to be greenish and are magnesium iron silicates and metamorphic. Serpentine is polymorphic in that several varieties look different while having the same chemical makeup. These varieties can make serpentine hard to identify. Noble serpentine almost resembles a common opal with a mostly rich lime green color. This particular variety of serpentine is different from others as it contains a high amount of calcium instead of iron.

With all of that fascinating history and present activity, a three-day trip to visit and rockhound with the Sahlis in eastern Washington was something not to be missed. The first day of my trip was spent driving over the Cascade Mountains and crossing into eastern Washington from the west. The drive is amazing, as it transitions from the lush evergreen forests of western Washington into the flowering plains of eastern Washington. Finally, as I made my way into the northeast corner of the state, I again entered a mountainous region full of tall trees and winding creeks, ultimately meeting Jim and Jennifer at their lake house. We hung out for a while and created a game plan for the next day.

We woke early the next morning, loaded into their vehicle and headed a short distance to the mine. Once we were past the gate, it was a rather steep and bumpy ride up Huckleberry Mountain to their mine site. Along the way, we saw a larger mine area also on the couple’s property. This area is what’s left of the workings from the great magnesite boom of the past, which created a thriving industry in this town so long ago.

As we came around a corner, my jaw dropped. In front of me was a small open pit mine that was glowing green. The entire area was nothing but noble serpentine! If there ever was a rockhound’s heaven, this is it. While the majority of the mountain is part of the Stensgar Dolomite Formation, there are intrusive sills that extend horizontally throughout. At this particular locality, the serpentine material has been exposed, revealing its huge potential. As it lays horizontally with a dip that strikes downward and a visible thickness of 30-40 feet thick, this deposit promises a lifetime supply of noble serpentine that those in the market nationally and internationally are starting to see.

Basic Methods Prove Successful

The Wild Turkey Mine is still in its infancy, so mining methods are basic. Upon entering the mine, we collected anything and everything that looked good. The entire mine is made of noble serpentine, so it’s plentiful pickings. However, I soon realized there is a lot more to it than I thought. The serpentinite rock forms in horizontal layers and each layer is a dramatically different variety of serpentine. After just a few years, the Sahlis have discovered numerous varieties. However, there is certainly plenty of the typical dark green variety of serpentine that is a much harder and excellent material for carving. Right below this primary layer, begins the classic noble serpentine variety that we have come to recognize. It has a gorgeous lime green, semi-translucent color with streaks of white throughout.

It will be exciting to see the future of the Wild Turkey Mine as new material is uncovered and lapidary ideas come to creation. I had a great time visiting these two wonderful people and receiving an in-depth tour of this century-old mine. While magnesite was the main concern in this area a century ago, the old-timers most certainly came across this deposit as a result. I can’t help but wonder what they thought of this stone and its most lovely green color.

For more information about Wild Turkey Mine and noble serpentine, to connect with owners Jim and Jennifer Sahli, or to purchase some of this remarkable material, visit www.washingtonrocks.net.