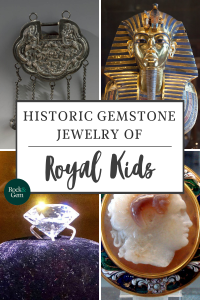

Historic gemstone jewelry wasn’t just for grown-ups. Some of the most exquisite earrings, rings, and charms were made for young royals. From Tutankhamun’s gold-and-lapis treasures to Alexander the Great’s engraved gems and Chinese jade lock charms, these glittering artifacts show that kids in history had serious bling—with stories to match.

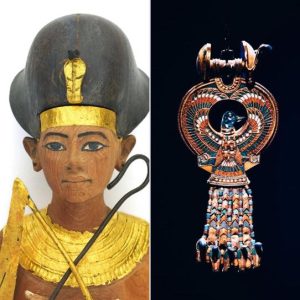

Tutankhamun’s Lapis and Gold: Historic Gemstone Jewelry Fit for a Young Pharaoh

Tutankhamun was named pharaoh of Egypt (1341-1323 B.C.) before he was 10 years old. The historic gemstone jewelry he’s best known for is a mask of (mostly) gold and lapis lazuli made to look like him. It was made to ensure his place in eternity, if not (since the discovery of his tomb in 1923) in pop culture, too. Egyptian goldsmiths were masters of inlaying semi-precious gems and colored glass. They also hammered surfaces using a technique called repouseé. This sunk a design into gold to create a realistic golden portrait of the boy king, including his pierced ears.

Courtesy FB Tutankhamun London-Clad/The Farm

Four pairs of earrings, in an oval-shaped cartouche, were among the historic gemstone jewelry found when the Tomb of Tutankhamun was opened. The Egyptian Museum in Cairo says this included a pair shaped like ducks. They have heads of translucent blue glass surrounded by cloisonné wings inlaid with quartz, calcite, colored faience and colored glass, and feet holding a rope-like shen-ring as stelae, or protection in the afterlife. To attach them to the lobes of his ears, Tut would have used a stud-like clasp made in two pieces so that it could be taken apart. Each piece had a short tube, closed at one end by a gold disk with a raised rim where a button of transparent glass was mounted. When the clasp closed, one tube fit inside the other.

Courtesy Roland Unger Wikipedia/ CreateCommons

The Origins of Earrings in Ancient Egyptian Gemstone Jewelry

When the earrings were attached, a microscopic portrait of Tut, in tiny pieces of colored glass, was visible behind each button.

In Tutankhamun’s day, earrings were a relatively new idea. They were likely introduced by Hyksos invaders who adopted the style from western Asia, where earrings had been worn for centuries. Tut may have been introduced to such jewelry by Shuttarna II, the Mitannian princess who (according to the El Amarna tablets) brought her jewelry, including earrings, with her to Egypt before marrying Tut’s grandfather, Amenhotep III.

Courtesy Wikipedia/CreateCommons

Alexander the Great’s Gemstone Legacy

Alexander the Great was 16 when, in 331 B.C., he seized the Persian Empire in the Battle of Gaugamela. He claimed so much Babylonian gold that it cross-pollinated jewelry-making cultures. Hellenistic historic gemstone jewelry styles were introduced to new corners of the world while native Greek artisans considered exotic new designs.

“After Alexander seized its treasures, vast quantities of gold passed into circulation. The market for fashionable gold jewelry exploded,” cite Colette Hemingway and Seán Hemingway, of the Department of Greek and Roman Art at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. “A variety of jewelry was produced in the Hellenistic period. Bracelets were worn in pairs according to Persian fashion, and jewelry was frequently produced in matched sets inlaid with pearls, gems or semi-precious emeralds, garnets, banded agates, sardonyx, chalcedony or rock crystal.”

The teen king also commissioned his own historic gemstone jewelry, using symbolic images like mythic beasts or monarchal wreaths. In an October 2023 blog, Greek jewelry maker Kotinos praised how complex Alexander the Great’s jewelry was as “a credit to ancient craftsmen.” It had filigree and granulation techniques in metalwork and developed some of the first stone setting and engraving techniques.

Image Barun Ghosh, Wikipedia/Creative Commons

The Nizam’s Jeweled Seal Ring and the Jacob Diamond

This Indian Nizam, or ruler, ascended to the throne in 1869 at the ripe old age of two. Imagine that! Among his royal gifts was a gold-and-spinel seal ring inscribed with the date he became prince and received a title longer than most jewelry: “The Rustan of the Age, the Aristotle of the Time, Fath Jang Sipah Salar 1302 (1184-85) Muzaffar al-Mamalik Nizam al-Mulk Mir Mahbub ‘Alikhan Bahadur Asaf Jah Nizam al-Dawlah.”

The gold seal ring, from the Al-Thani Collection at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, carries a hidden key that folds beneath a hinged top described as, “A secret of the wearer, who extended it only when needed to open the mystery lock into which it fits.”

Courtesy Wikipedia/Creative Commons

Lucky Locks and Jade Charms in Ancient China

Boys growing up in China’s Ming Dynasty (1368-1644 B.C.) wore a single ring-shaped earring as an amulet against evil spirits. By the Qing (1644-1911 B.C.) Dynasty, good jewelry had to bring good luck, in hopes of passing a trio of Civil Service Exams that could make or break a boy’s future, according to Terese Tse Bartholomew, former curator at the Asian Art Museum in San Francisco, via Ben Marks at Collectors Weekly.

“A major preoccupation of Chinese iconography concerned the education of a family’s sons. Jade objects were decorated with three round rings, meaning ‘May you give birth to a son who can pass the three Civil Service examinations,’ because if you passed all three, you were set for life.”

Speaking of locks: Baby boys received lock-shaped talismans to keep a child ‘locked to the earth’ (and protected from death). Wealthy Chinese families gifted jade, gold or silver locks, but for a son born to a poor family, his parents may ask for a penny apiece from 100 families, assuring the purchase of a lock and the protective goodwill of a community. The popularity of Chinese lock jewelry depended on supplies of silver, a historically rare metal until imports came from Japan and the Spanish Empire.

Courtesy Wikipedia/Creative Commons

Cornelia’s Real Treasures: A Roman Take on Jewels

The month of May also marks Mother’s Day, and behind young rock and gem collectors are often Moms supporting their kids’ interests. It’s a story as old as ancient Rome itself.

Cornelia Africana was the sophisticated daughter of Publius Cornelius Scipio Africanus Major, the hero of Rome’s Second Punic War against Carthage. She grew up appreciating the importance of education and, after her own husband’s death, the Roman widow and matron devoted herself (to a legendary degree) to her children.

According to the first-century Latin writer, Valerius Maximus, Cornelia and her children were dining with a wealthy friend who, after the meal, instructed a servant to bring out a jewelry box full of the host’s own rubies, sapphires and pearls.

She asked her guest, “Is it true, Cornelia, as I have heard whispered, that you are poor?”

“No,” was the mother’s famous reply as she hugged her children. “For these are my jewels. They are worth more than all your gems.”

This story about historic gemstone jewelry previously appeared in Rock & Gem magazine. Click here to subscribe. Story by L.A. Sokolowski.