By Steve Voynick

Cryolite is something of an enigma among minerals. It is rare, and its only significant deposit is located on the remote coast of Greenland. Nevertheless, cryolite was once of critical industrial and strategic importance. And it is the only mineral that has ever been mined to commercial extinction.

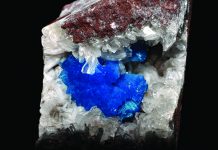

Cryolite, or sodium aluminum fluoride (Na3AlF6), consists of 12.85 percent aluminum, 54.30 percent fluorine, and 32.85 percent sodium. It crystallizes in the monoclinic system, but occurs primarily in massive form. With a Mohs hardness of 2.5 and a specific gravity of 2.98, cryolite is much softer and a bit denser than quartz. Usually colorless, white or gray, it is transparent to translucent and exhibits a vitreous-to-pearly luster.

Because its refractive index approximates that of water, transparent, colorless cryolite becomes almost invisible when placed in water. And cryolite is not only ice-like in appearance; its name, which stems from the Greek words kryos, or “ice,” and lithos, or “stone,” means “ice stone.” Greenland’s indigenous Inuit called cryolite “the ice that never melts.”

Commercial Source Connection

Cryolite’s sole commercial source is located at Ivittuut (formerly Ivigtut) on Arsuk Fiord on Greenland’s southwest coast, where it occurs atop a granitic intrusion within a mineralogically complex pegmatite that is the type locality for cryolite and 16 other rare minerals.

Also present in this pegmatite are argentiferous galena, sphalerite, fluorite, chalcopyrite, pyrite and, most notably, well-developed, reddish-brown crystals of siderite.

After studying specimens collected at Ivittuut, the Danish physician Peder Christian Abildgaard described and named cryolite in 1799. Mining began at Ivittuut in 1854, with cryolite first used as a minor source of aluminum, then as a raw material for manufacturing caustic soda (sodium hydroxide).

Realizing Potential

Metallurgists of the mid-1800s realized that strong, lightweight aluminum had enormous industrial potential. But the metal could only be extracted in small amounts from cryolite and several other rare minerals. Although aluminum was present in huge quantities in alumina (aluminum oxide) in abundant bauxite-type deposits, it could not be economically separated.

But in 1884, American and French chemists learned to dissolve alumina in molten cryolite, then to inexpensively extract metallic aluminum by electrolysis. This discovery, patented as the Hall-Héroult process, finally made aluminum affordable. It also sharply boosted demand for cryolite which, for the next 50 years, was critical in the development of the modern aluminum industry.

By 1900, the Ivittuut mine consisted of a steadily expanding open pit, living quarters, machine shops, loading docks, a medical clinic, and a 175-man crew.

Protecting The Pits

Because the Greenland climate limited mining to summer, miners flooded the pit with seawater in autumn to prevent it from filling with snow. Each spring, they would break the ice and pump the water out. Between April and October when the sea was clear of ice, ships loaded the cryolite for delivery to ports in Europe, the United States, and Canada.

During the 1930s, the availability of synthetic sodium aluminum fluoride began to reduce the demand for natural cryolite. But during World War II, the critical need for aluminum demanded huge quantities of both natural and synthetic cryolite. Because of Ivittuut’s strategic wartime importance, United States Army troops guarded the mine to prevent it from falling into German hands. Ivittuut’s production peaked in 1942 when it mined and shipped 85,000 tons of cryolite to North American aluminum smelters.

Following the war, the mine continued to expand with a 1,500-foot-long inclined tunnel and workings as deep as 200 feet below sea level. By 1962, when the deposit was declared mined out, Ivittuut had produced 3.7 million tons of ore grading 58 percent cryolite. Mining operations then ceased, and only small crews remained to clean up the old dumps. In 1987, Ivittuut was abandoned.

Today, specimens of Ivittuut cryolite are reminders of the world’s first and only commercial cryolite mine—the source of the “ice that never melts.”

Author: Steve Voynick

A science writer, mineral collector, and former hard rock miner, he is also the author of many references including, “Colorado Rock Hounding” and “New Mexico Rockhounding.”

A science writer, mineral collector, and former hard rock miner, he is also the author of many references including, “Colorado Rock Hounding” and “New Mexico Rockhounding.”

Learn more about Mr. Voynick from his site: Mountain Press Publishing.