By Helen Serras-Herman

The town of Jerome was founded in the late 19th century on top of Cleopatra Hill of the Black Hill Mountains. The Cleopatra Hill is situated at 5,200 feet and overlooks the Verde Valley below. Jerome is about 100 miles north of Phoenix, along scenic State Route 89A that connects the famous Red Rocks of Sedona to the northeast, and the town of Prescott to the west.

The mining town of Jerome popped-up in temporary tents in the 1870s soon after the discovery of copper by three prospectors. The town was founded as a copper mining community in 1876 after the first claims were filed. The original prospectors sold their claims in 1880 to Frederick Tritle and Frederick Thomas, who, with the help of eastern financiers James McDonald and Eugene Jerome, created the United Verde Copper Company in 1883. Ironically, Eugene Jerome never visited the town, he only asked for it to be named after him.

That company only lasted two years, and the new owner, William Andrews Clark, a senator from Montana, had the vision to bring a narrow-gauge railroad to transport the ore, thus helping reduce the freight costs, and made the United Verde a successful mining venue and the largest copper-producing mine in the early 20th century Arizona Territory.

After multiple problems at the United Verde, including a geologic fault line, fires on the 400-foot level of sulfide ores, and the beginning of an open pit operation, the smelter was relocated from Jerome to the nearby new town of Clarkdale. It was completed in 1915. (Read more about Clarkdale in my article Taking a Closer Look at Copper, R&G August 2019).

Early Challenges At the Mine

After the financial crash of 1929 and the onset of the Great Depression, the price of copper sunk to five cents per pound, and by 1932 the United Verde mine closed (Jerome, Story of Mines, Men and Money, Western National Parks Association, 1993). Following Clark’s death in 1925, the mine was sold to Phelps Dodge in 1935, only to be shut down in 1953.

The two mines in Jerome that produced over 84 billion dollars in recovered metals were the United Verde Copper Company and the United Verde Extension (U.V.X. or Little Daisy), which was purchased in 1912 and developed by James S. Douglas. The mines produced the mind-boggling amount of three million pounds of copper per month and were dubbed the Billion Dollar Copper Camp. Jerome was once known as the wickedest town in the west, although I am sure several other mining towns were vying for that same title.

Long before the area was the location of a mining boom, it was populated by the Sinagua Native American people who farmed there from as early as 700 BCE until 1125 BCE. They surface-collected malachite and azurite and used it for jewelry and pigments.

The region was later visited in 1583 and 1598 by Spanish explorers who made note of the ore but were not impressed and did not mine, as they were only interested in gold or silver. Although much later, a lot of gold and silver came out of the ground around Jerome, but it was copper that put Jerome on the map. By the late 1880s, copper had become an important and much-in-demand metal, as it was necessary for manufacturing electrical wires, still in great demand today.

Today the town is an artist community and a historic tourist destination. After the copper ran out and the mines closed in 1953, the less than 100 residents at the time promoted the area as a ghost town to get travelers’ attention. In 1967 Jerome received the designation of a National Historic District.

Taking In Jerome

A good first stop in town is at the Jerome Visitor’s Center, sponsored by the Jerome Chamber of Commerce, where visitors can get maps and information about all the attractions, shops, and dining facilities. The town is a mix of old façade buildings, some renovated, some that are ready to slide off the hill, and some with their resident ghosts. In fact, some of the buildings have slid off the hill, such as the famous Sliding Jail, due to geologic faults running underneath the ground, but primarily due to the constant blasting in the mines. The town is built on a steep 30-degree angle mountainside above the mine, so be prepared to walk uphill and downhill around town.

The Jerome Historical Society Mine Museum

The Jerome museum is located in the heart of Jerome, at 200 Main Street. Visitors enter the museum through an expansive gift shop that offers souvenirs and books, with all proceeds going to the Jerome Historical Society’s fundraising efforts.

The museum opened in the early 1950s. The exhibits follow the timeline of Jerome and highlight the stories of the tough men that built the town. The miners’ life was hard and often dangerous, spending 10 to 12 hours underground, drilling and hauling rock around. The little money they earned was an easy target from boarding houses charging for room and meals, at least 27 saloons and brothels with prostitutes, like the Black Cat and the Cuban Queen, all eager to please the miners.

Exhibits are honoring all the immigrants that were part of Jerome’s fabric: the Italians, Slavs, Irish, Russians, Mexican (which were a large part of the population), and the Chinese. I was truly taken by those artifacts and photographic exhibits. There is a Chinese wooden laundry washing machine, with crank and gear mechanisms to agitate and spin the laundry.

Also on display is a beautifully decorated opium box. There were at least 60 Chinese, mostly men, living in Jerome in 1900, although that number dwindled to 34 by 1910. Many of the Europeans that came over from the “Old Country” had prior mining experience and went directly to work in the mines. The Chinese performed some of the hardest jobs, such as railroad work, cooking, and laundry services, all demanding and back-breaking jobs that nobody else wanted.

There are also some great exhibits of mining equipment, such as drills, carbide lamps, hand-forged miner’s candlesticks, and ore carts. On display is a unique artifact, an underground double “potty car,” as the underground sanitation rules were strictly enforced. This portable bathroom was for men only, as women were seldom in the mine tunnels. Another interesting artifact is a small iron model that was used to teach new miners how to dump the ore car. Also on display is an iron cage, or elevator, which miners used to get down to the mine, with the sign “Cage Call, Push Button: Going up- 1, Going down-2”.

Intriguing Artifacts and Exhibits

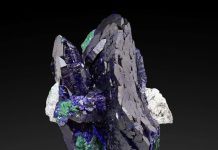

During our visit, we were drawn to a wonderful, small but representative mineral

exhibit representing those found in this area, including azurite-malachite, azurite crystals, chalcopyrite, and the famous “Apache gold,” which is the trade name for a unique metallic rock of chalcopyrite in jet-black chlorite schist. This uncommon rock is found only in the “Big Hole” at the United Verde Mine in Jerome. Also on display are specimens of cuprite and native copper, and peacock ore (chalcopyrite, bornite, pyrite, and marcasite) from the United Verde Mine.

There are additional artifact exhibits that include pistols from vigilantes, household goods, a hospital ambulance car, and photographic exhibits about the Jerome hospital, as well as gambling paraphernalia.

The Jerome Historical Society Mine Museum is open daily from 9 am to 5 pm or 6 pm depending on the season. Admission is $2 for adults and $1 for seniors. For more information, visit https://www.jeromehistoricalsociety.com/museums-buildings/mine-museum/ or call at 928-634-5477.

The Jerome State Historic Park- Douglas Mansion

This park is located at the town’s entrance. It became a State Historic Park in 1965, and it includes a museum inside the landmark residence of James S. Douglas, the mine owner of the United Verde Extension (U.V.X. or Little Daisy Mine). The park was closed for renovations for over a year and reopened in 2010. Comparing to our 2007 visit, the entrance is relocated to the right of the building, and all of the outdoor mining equipment and large specimens are now accessed from inside, after entering the museum.

Just before visitors reach the Jerome State Historic Park-Douglas Mansion, they’ll first encounter the historic Audrey Shaft Headframe from the Little Daisy Mine, constructed to haul ore out of the mine. The original wooden structure, completed in 1918, was replaced in 1981 by the current steel version, still standing today. The shaft is 1,900 feet deep and visitors can stand above it on a glass base. The shaft has several cross tunnels occurring every 100 feet. The Audrey Headframe is part of the Headframe Park, managed by the Jerome Historical Society. The Little Daisy Mine consists of 4 claims and lies east of the United Verde Mine.

The Douglas Mansion, the home of James Stuart Douglas, was built on top of the hill in 1916 just above his Little Daisy Mine. Douglas designed the house to be not only his family’s private residence but also a hotel for mine officials. The panoramic views of the old mines and the town are a big attraction for many visitors today. The house was built with over 80,000 adobe bricks, which was a point of pride for Douglas. The bricks were made by a special crew of adobe men, who mixed dirt, straw, and water by hand, dumped the material in a three-brick ladder-like frame, and sun-dried the bricks on site. One of the original adobe bricks remains on display. The mansion was used as Douglas’ residence until the mine closed in 1938.

Douglas’ father, Dr. James A. Douglas, was a mining engineer and the first president of Phelps Dodge Corporation. He was sent to evaluate the copper ore in 1880, but even though he liked the color of the copper, he didn’t like the distance to the market and advised financiers not to invest.

Striking Copper

Two years after James S. Douglas purchased the Little Daisy Mine, he was on the verge of shutting down, when he hit the richest copper vein, which made the Douglas family rich and prominent. Almost four million tons of ore were extracted from the mine, between 1915 and 1938, which produced 297,000 tons of copper, 221 tons of silver and 5.5 tons of gold. Compared to the United Verde Mine, the Little Daisy Mine was only 1/10 in size but accounted for over 20% of the total copper production in the Jerome District.

Ore was hauled out of the mine and transported by tram or burro train to the railhead in the valley. There is a wonderful historic photograph inside the museum from 1915 showing an 18-horse and mule team in the Verde Valley transporting 14,000 lbs of ore.

The museum is dedicated to preserving and sharing the history of Jerome, the mines, and the Douglas family story. Exhibits feature artifacts, photographs, and a 3-D model of the underground mines, as well as a great mineral exhibit. A continuously-running short video presentation offers insight into copper mining and the lifestyle of the area’s residents. Visitors enter the museum at the Douglas library, which is a restored room with period furniture. Upstairs there is also a bathroom furnished in period furnishings.

There is an entire wall with great displays of minerals, mostly copper-related ones. Local azurite-malachite from the Little Daisy Mine, malachite-cuprite, and native copper specimens, along with a large botryoidal azurite specimen from the private collection of Lewis Douglas (the son James Stuart) that was returned to Jerome by the Museum of Natural History in New York. Also in that same cabinet is a large specimen of copper ore from the #1407 stope of the U.V.X. (the United Verder Extension or Little Daisy Mine), composed of 46.8% copper, chalcocite, tenorite, covellite, malachite, quartz, feldspar, and calcite. It is from a large body of copper ore, which averaged 45% copper, one of the richest copper strikes ever found. Also on display is a beautiful botryoidal malachite specimen from the Copper Queen Mine in Bisbee.

The next case displays mostly volcanic Precambrian rocks from the Early Proterozoic Era (2,500 to 1,600 million years ago) from Jerome. Among them are the oldest called “pillow basalt” lava flows, as well as andesite and Deception Rhyolite lava flows. The last mineral display case exhibits gemstones. Among the highly ranked Arizona gemstones in the US Geological Survey are turquoise, peridot, and petrified wood. Also mined in Arizona are amethyst, apache tears, azurite, chrysocolla, fire agate, garnet, malachite, obsidian, onyx, and opal, and a number of them are on display here.

Making the Most of Museum Visits

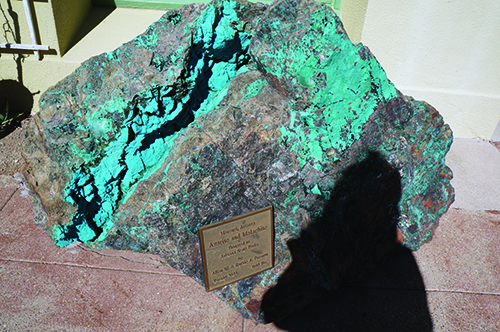

After walking through the museum galleries, visitors can step outside to an area

filled with interpretive panels that explain the buildings in view, and various historic mining equipment, such as mine ore carts and barrels.There are also large specimens of azurite-malachite from the Morenci copper mine. This is a great spot to enjoy a panoramic overlook of the Cleopatra Hill and the entire town and mines, and envision a vibrant, 15,000-resident, hard-working community over 100 years ago.

The Jerome State Historic Park is open daily from 8 am to 5 pm, with special holiday hours. The museum is open from 8:30 am to 4:45 pm. The entrance fee to the park is $7 for adults. There is a wonderful gift shop inside the museum, with a good selection of books and souvenirs, and Arizona copper commemorative coins, which we always find irresistible and a great gift for our friends and family.

For more information, visit www.azstateparks.com/jerome. Jerome is part of Arizona’s history and the people that lived there, many of them to work in the mines. By visiting both mining museums in Jerome, one may begin to understand the importance of copper in society and the hardships that the miners endured back then and still do today, although most mining nowadays is done in an open-pit and not in dark, underground tunnels.

Even though most of the copper ore in Jerome is exhausted, there is still some mining exploration taking place, and one suggested option is to scrape the entire town to recover the low-grade ore. My husband and I have seen this happen back east in the coal region near his hometown of St. Clair, Pennsylvania, and we hope that this will not happen to Jerome. Hopefully, there are enough visitors to keep the town and its history alive.