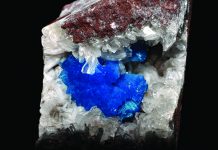

Pegmatite can be likened to a Tiffany box holding a shiny surprise inside. An otherwise coarsely textured, igneous rock, pegmatite’s large, interlocking crystals are a “big daddy” among gem lovers. Many of the world’s largest crystals (some 33 feet long or more) have been found in pegmatite, including beryl, mica, microcline, quartz, spodumene and tourmaline.

Yet it has really only been in the last 10 years that we’ve better understood what makes pegmatite crystals grow so large, says Dr. William ‘Skip’ Simmons, Research Director at the Maine Mineral & Gem Museum, and coauthor of Pegmatology: Pegmatite Mineralogy Petrology and Petrogenesis, with Karen Webber, Alexander Falster, Encar RodaRobles and Don Dallaire (Rubellite Press).

Enriching this magma-formed rock with water, Dr. Simmons says, “Grows big crystals in a short amount of time.”

Minas Gerais

Minas Gerais or ‘General Mines’ is a deceptively innocuous description of a network of veins across a 90,000 square mile region of southeastern Brazil. These veins have lured men into their depths for nearly 500 years, and established colonial Brazil’s early capital, Ouro Prêto, as the epicenter of a nation’s Golden Age and one of the largest and wealthiest cities anywhere in the New World.

Diamonds and gold seduced the first wealth seekers but in the 21st century, pegmatite and its spectacular crystals are large and in charge.

Brazilian “Emeralds”

If growing crystals takes time, it also took centuries to correct an error by overeager explorers in search of diamonds and gold, who found pegmatite instead and mislabeled the green stones they unearthed as “Brazilian emeralds.”

Because who hasn’t been guilty of a little embellishment if it keeps the boss happy?

The 1554 expedition of Francisco Spinoza and his Bandeirante (named for the banners its horsemen carried) was disappointing to the Portuguese crown with its failure to find gold — despite laboriously breaking trail ever further inland along the Jequitinhaha River. According to Gem Pegmatites of Minas Gerais by Colorado gem importer Keith Proctor, “It is highly likely that Spinoza’s men brought back the world’s first recorded gem tourmaline.”

Or at least what constituted records keeping five centuries ago. A woodcutting published in 1565 in De Rerum Fossilium by Swiss naturalist Conrad Gesner of an “elongated striated crystal with a pointed termination,” was entitled, “Smaragdus Bresilicus cylindri specie,” (“A cylindrical species of Brazilian emerald”).

“The appearance and description of this striated crystal,” Proctor wrote in his 1984 article for the Gemological Institute of America, “indicate that in fact, it was tourmaline.”

Besotted by their discovery of the green stones of local lore and eager to keep royal benefactors placated, Portuguese explorers presumed the gems were emeralds. Ensuing expeditions in 1568 and 1571 fanned the flames of misidentification further when, north of the headwaters of the Suacui Grande River (site of future Cruzeiro and Golconda tourmaline mines), reports came of more emeralds, as well as sapphires and turquoise.

In truth, they were green and blue tourmaline and blue beryl crystals. It would take another 100 years before the discovery of the first recorded pegmatite, and two more centuries after that before Brazilian pegmatite gemstones started getting credit where credit would prove amply due.

Courtesy Wikipedia Creative Commons

The Emerald Hunter

Fortune-hunting frontiersman Fernão Dias Paes Leme was the Indiana Jones of his day. When the Portuguese Bandeirante embarked on a final journey from São Paolo in 1674, he was intent on finding the New World’s fabled Emerald Mountains. The undertaking took nearly seven years, and malaria cost Paes Leme his life. But not before, Proctor recorded, “In the immediate vicinity of today’s famous Cruzeiro mine and village of São José da Safira (misnamed “sapphire” for the blue tourmaline found), Paes Leme discovered the first recorded pegmatite – a mountain of mica with the green crystals of his dreams.”

A total of 128 gems, including Brazilian emeralds, aquamarine and topaz, were found and shipped to Lisbon in 1682 and Portugal in 1698, where experts familiar with emeralds from India dubbed the stones “worthless tourmaline.”

Paes Leme’s discovery was ignored for nearly 200 years, Proctor explained because there was no significant market for Brazilian pegmatite gemstone.

Not, that is, until 1811 when a nearly 15-pound crystal as green as grass – the first large Brazilian aquamarine on record — was culled from the headwaters of the São Mateur River.

A year later, British mineralogist and jeweler John Mawe, who under the authority of Brazil’s Prince Regent had toured the mines of Minas Gerais (1809-10), released his illustrated account, Travels in the Interior of Brazil. Pegmatite and those big, beautiful crystals were finding their spotlight.

Armadillos & PegmatiteWhat do “possums on the half shell” have to do with Brazilian pegmatite? If you love watermelon tourmaline, you might want to thank an armadillo. The Santa Rosa mica mine in southwest Itambacuri was abandoned after World War II until garimpeiro, or wildcat miner, Tiao Matias, noticed sparkles inside armadillo burrows. He started digging out druses of tourmaline and going deeper, struck quartz crystals encrusted with gemmy pink and green bi-colored crystals. “Eventually the miners moved into the hard-rock pegmatite of Santa Rosa Hill. Interestingly, the hard-rock tunnels yielded fewer gem quality tourmalines than the original colluvial deposits,” Proctor wrote in Gem Pegmatites of Minas Gerais for the 1984 Gemological Institute of America. Maybe the armadillos knew when to stop. The October 12, 1967 Santa Rosa strike remains the most important in the mine’s history, and for three brief but spectacular years, yielded tons of gem- and specimen-quality tourmalines. |

Big Deals

A big impact on Mina Gerais and its mining came in 1910 when one of the largest aquamarine crystals (244 pounds) of the century was found less than a meter from the bottom of a Marambaia valley pit. Proctor said the 19” x 15” blue-green, doubly terminated hexagonal prism found was so flawless and transparent, “One could read print through it from end to end.”

Courtesy Wikipedia Creative Commons

The Papamel Aquamarine proved too large in size or sum, so when no museum or institution came forward to buy it in its entirety, it was cut up and its pieces sold individually. The only uncut piece of the Papamel remaining is a nearly 6-kilogram remnant on display in the J.P. Morgan gem collection at the American Museum of Natural History in New York City.

“News of the selling and asking prices for the Papamel precipitated a flurry of activity by Brazilian miners and German dealers. This enthusiasm stimulated the search for aquamarine and eventually contributed to the development of entire central and northern portions of the Mina Gerais pegmatite region,” Proctor wrote.

In September, Dr. Simmons led the Maine Mineral and Gem Museum’s 21st Annual Pegmatite Workshop, and TGMS co-chair Mark Marikos confirmed Dr. Simmons will be joining its lecture series at Tucson.

“We always have Brazilian pegmatite. They produce such spectacular specimens” says Marikos, who sees in pegmatite the past meeting the future. Water, last to crystalize in nascent magma, becomes a time capsule forever holding ancient minerals deep inside.

“Pegmatites are still considered difficult to comprehend,” says Dr. Simmons. “They are individually diverse in structure, mineralogy, and paragenesis but, simultaneously, there are enough similarities between all pegmatites to be worthy of comparison and study by the miner, mineral collector, and academic alike.

“I’m proud of how pegmatite workshops bring hardcore professionals together with people just starting to learn about them. I love it,” he says, adding with a grin, “If you haven’t heard of pegmatite before, you will now.”

This story about pegmatites previously appeared in Rock & Gem magazine. Click here to subscribe. Story by L.A. Sokolowski.