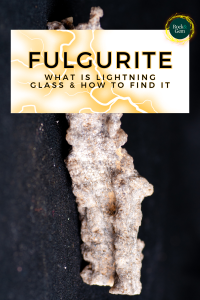

Fulgurite — from the Latin fulgur, meaning “thunderbolt” — is a natural tube or crust of glass created when heat from a lightning strike or downed power line fuses silica (quartz) sand, rock or other mineral grains. They are sometimes known as fossilized lightning and their shape can emulate the path of the lightning bolt as it made contact with the ground. Fulgurites were made famous in the 2002 movie “Sweet Home Alabama.”

While they’re not easy to find to the untrained eye, experts share helpful tips, personal encounters and fun facts about these electrifying specimens. Sand fulgurites are routinely uncovered in deserts and on sandy beaches.

“One strike can create a lot of fulgurites, but once they’re exposed, they quickly break down, within a week,” said geologist Andrew Valdez, who is employed at Great Sand Dunes National Park & Preserve in Mosca, Colorado. “You can find them exposed after big wind events.”

He noted this variety requires careful handling and storage.

“You have to treat them like very thin glass. If you wanted to preserve one, you could put it in liquid acrylic, which hardens. That would be the best way to do it,” Valdez explained. “You can also put it in a specimen display —a glass box. It’s best not to handle them.”

Where & How

Lake Maracaibo in Venezuela receives more lightning strikes than any other place on the planet. Florida is the lightning capital of the United States and the city of Fort Myers endures more thunderstorms than anywhere else in the state.

As the National Weather Service explains it, lightning can heat the air it passes through to 50,000°F, which is five times hotter than the surface of the sun. “Height, pointy shape and isolation are the dominant factors controlling where a lightning bolt will strike. The presence of metal makes absolutely no difference in where lightning strikes. Natural objects that are tall and isolated, but are made of little to no metal, like trees and mountains, get struck by lightning many times a year.”

Paleolightning, which looks at the remnants of ancient lightning activity, helps inform theories crafted by historical geologists, geoarchaeologists and fulminologists. By studying lightning activity in the Earth’s past (including the formation of fulgurites) these scientists gain insights into the impact of lightning on the Earth’s atmosphere.

Unique Chemical Reactions

Matthew Pasek, a geoscientist at the University of South Florida in Tampa, has studied how lightning can cause unique chemical reactions.

“The average fulgurite is straw-like and pretty much all of the interior is glass.

The outside is going to be baked rock — dehydrated,” Pasek said. “The sand variety is thin and long. Ones formed in clay or rock and or from a downed power line are bigger.” In March 2023, he co-authored a paper, “Routes to Reduction of Phosphate by HighEnergy Events” where he explained that a new compound was created by lightning in a fulgurite that was uncovered in New Port Richey, Florida.

The paper reads in part: “A calcium phosphite material, ideally CaHPO3, was found in spherules mainly consisting of iron silicides that formed by lightning-induced fusion of sand around a tree root. This phosphite material bears a phosphorus oxidation state intermediate of that of phosphides and phosphates in a geologic sample and implicates phosphites as being potentially relevant to other high-energy events where phosphorus may partially change its redox state, and material similar to this phosphite may also be the source of phosphite that makes up part of the phosphorus biogeochemical cycle.”

Downed Power Lines

Fulgurites created by electricity from downed power lines are highly collectible.

“Lightning will have more power, but it dissipates quickly,” Pasek said. “A downed line could be live for hours and create large fulgurites.”

He noted an easy way of determining what type of heat source formed a fulgurite is to see if it contains copper or aluminum which comes from a melted power line. “Otherwise the differences can be subtle,” he added.

Courtesy Brennan Cassidy

Unusual Fulgurites

On July 27, 2023, a lightning strike in Springfield, Massachusetts, created a specimen weighing over 150 pounds — which is extremely uncommon.

“In addition, this lightning struck an electrical wire first and resulted in some aluminum and copper specimens with exogenic fulgurite form, possibly some gold too. I am having it tested,” said Brennan Cassidy. “I have submitted to the ‘Guinness Book of World Records for the heaviest fulgurite specimen but have not heard back yet. I am definitely a rock collector, but I am a dentist —and teeth are minerals —so I also consider myself a rock doctor.”

The most exotic example of specimens Pasek has encountered was created from a termite mound in Australia, made up of hematite and iron oxides.

Mark Milligan, a geologist with the Utah Geological Survey, said you might detect bubbles of trapped air inside because it requires a temperature of 1,800°C to instantly melt sand and form a fulgurite.

Mountains & Fulgurites

“While hiking in the summer of 2003, I discovered both sand and rock fulgurites on some of the higher summits of the Wasatch Range,” he wrote. “I observed very small sand fulgurites (an inch or less) in some of the surface float on top of Mount Raymond (10,241 feet) and Broads Fork West Twin (11,328 feet). I also found rock fulgurites on top of Mount Raymond, Broads Fork West Twin, Mount Baldy (11,068 feet) and Mount Timpanogos (11,749 feet). Some of the rock fulgurites, such as those found on Mount Timpanogos, are the result of human activity (a steel shelter placed on top of the peak attracts lightning).”

Milligan added that rock fulgurites form on mountain peaks where quartzite is present. This variety may require extraction compared to sandy fulgurites, which tend to have less mass and are easier to move.

“Some of them are in float, and others would require a rock saw, which you shouldn’t be using (in a state or national park),” he said. “Look for something that seems out of place, and within a few feet of the peak. That could be a fulgurite. Rock ones can be harder to recognize than the sand kind.”

Courtesy Matt Pasek

Safe & Acceptable Finds

Make sure to do your research when it comes to what lands are available to the public to excavate and rockhound.

Milligan said to always practice safe removal, “I would hope nobody would go near a live power line. Wait until a storm has passed before approaching a site,” he said. “I have heard of scientists doing experiments with lightning rods on beaches to petrify sand. I have not done that myself.”

Gypsum Fulgurites

Fulgurites made from gypsum, such as those found at White Sands National Park in New Mexico, do not contain glass. Gypsum is a calcium sulfate and does not contain SiO2. Most collectors are not as familiar with these.

“I have not heard of gypsum fulgurite, but I do have a piece of ‘phytofulgurite’ from the find, where a biomass is replaced by fulgurite and maintains the same form of the matter it is replacing,” Cassidy explained. “In this case, it is a piece of a seed sprout that was replaced by aluminum from the electrical wire that got struck before the lightning hit the ground.”

Color & Type

Cassidy said it’s more enjoyable to study fulgurites he finds rather than to purchase them.

“For me, a good fulgurite specimen has a few branches, a mostly hollow core, and a dense outer shell. I prefer exogenic specimens since these are more in line with good ‘crystal’ structure —resembling botryoidal minerals —and luster, as they lack the dirty outer surface that most fulgurites acquire after cooling in the ground,” he noted. “Some of the exogenic pieces also have differing colors due to the mineral content of the soil. For example, one has a significant red color likely due to the presence of iron. If I were to add some to the display cabinet, I would highlight the smooth contours and spherical shapes of the exogenic pieces with indirect light.”

Fulgurites can also be green, black, tan, gray, gold or white.

“The color is going to depend on what material was struck,” Milligan said. “Some of the ones Carl found are pretty white. I have samples that are green.”

Courtesy Matt Pasek

Hunting & Buying Tips

If you’re on the hunt for fulgurites, be sure to be plugged into weather alerts for where electrical storms may occur. You can also cultivate contacts within the power industry to see if you can obtain specimens found by employees. Policies will vary from company to company. If you encounter a downed line that isn’t actively sparking, don’t assume it isn’t still carrying electricity. Stay at least 30 feet away from a downed power line and do not approach it to look for specimens until it has been fixed.

If you end up buying fulgurites, make sure the seller carefully packages the pieces to ensure safe delivery. Fulgurites are sourced from the Sahara desert, the French Alps (Mont Blanc), the Pyrenees Range and western U.S. mountain ranges. The variety from Libya is formed from pure white sand and is highly desirable. Some how-to videos and articles instruct how to make lab-created fulgurites.

No matter how you go about collecting fulgurites, make sure to do research, buy only ethically sourced specimens and have fun!

This story previously appeared in Rock & Gem magazine. Click here to subscribe. Story by Sara Jordan-Heintz.