Lake County diamonds display color effects similar to genuine diamonds. Such similarity has led to countless specimens faceted and worn. Rainbows, moon legends – this is the true California culture of light and romance. These are objects borne of violent eruptions that people hold up to the sun in wonder.

Finding Lake County Diamonds

I found it lying in the middle of a dirt road among vast vineyards near Cobb Mountain, overlooking Clearlake, California. It looked precisely like a piece of broken glass from an amber beer bottle, but multi-million-dollar vineyards that make glass litter seem unlikely. I also knew that the road crossed the epicenter of Lake County diamond country.

The specimen I found was a xenolith, formed from molten silicon dioxide contacting a coloring element, somewhat as a glassblower fashioning decorative glass. The high-temperature environment within the magma chamber of Mount Konocti, 1,112 degrees at a minimum, gave it a 7.5 or higher Mohs Scale of Hardness and allowed absorption of the coloring element. The resulting “diamond” was not merely stained quartz but a gem.

Many thousands of years after its origin in a volcanic eruption, the road grader bit deeper into the earth and uncovered it.

Lake County Diamonds – Variants

My find was an unusual variant of a typically colorless gem, with lavender and yellow specimens predominating. Though visually crystalline, the colorless specimens that lie about freely here are not crystals, which form at lower temperatures, but fragments of clear magma.

A brilliant luster defines these stones. As I walked along, inspecting the graded furrows lining the road, glints of light caught my eye. Only millimeters in size typically, the pure “diamonds” emitted signals of light. The atmosphere, measured as the most pollution-free in California, helped raise their visibility. At home, their brightness reminded me of the high-priced Lake County diamonds set in jewelry online.

These stones shine at the end of a 115-mile drive north of San Francisco that leads through Napa Valley into Clearlake, part of the northernmost volcanic field of the California Coast Range. Napa itself derives commercial energy from geothermal power plants here, which number more than any other place in the world.

The specimens simply came to me. My only expedition tools were a rental car, internet directions, a stick to dig with, and running shoes for comfortable walking. In a place of wealthy vintners, it seemed only right to pick them off of a dirt road. They are a component of the local culture.

Lake County Diamonds – Early Culture

These stones played a dramatic role in the culture in the 19th century. In those days, the Pomo Indians took note of the stones’ brightness and placed them on grave sites so that moonlight would shine on them and frighten away spirits of darkness.

They fashioned a creative legend holding that their brightness derived from a love affair between the moon and a chieftain. As the story goes, the moon sang to the chieftain, and golden dust filled the sky. The sun, jealous of the golden color, killed the chieftain and the moon hurled Lake County diamonds at the sun in anguish, some of them becoming stars in the night and others falling to earth near Cobb Mountain.

Early European settlers regarded the authors of this legend as savages and made them slaves. A slave uprising followed, during which the cavalry surrounded a village of defenseless native fishermen on Bloody Island in Clear Lake and waged genocide upon them. There is an effort underway to recognize the 1850 tragic event with a monument.

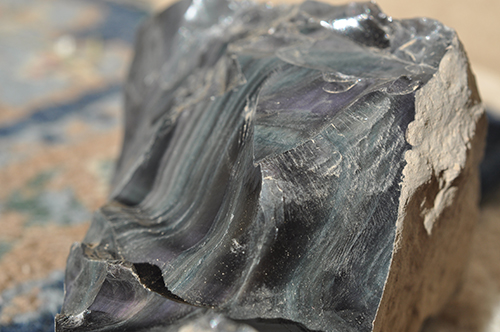

At Beaver Creek Vineyards, during this more civil age, a heart-shaped tray of these gems sits on the oak counter where visitors sample organic red and white wines. The proprietor gave me a large diamond, much larger than my quarter-inch best-of-hunt specimen, and the casual way he did so made me envious and hungry for a second hunt resulting in a large specimen. Then I saw a monolithic hunk of black obsidian among the rustic furniture.

Digging for Obsidian

This impressed me, but there was no envy, since a couple of days earlier, I had dug gem obsidian, which I reached after considerable travel in rough country. The environment was less civil, and my success depended on a pick, a rucksack, and common sense regarding landscape.

The gem obsidian in this area only yields to those who endure a long drive into a different kind of place. A place with a road sign advising “No Services for Next 87 Miles,” where empty highways run through a vast territory of conifer-fringed ranches and cowboys in pickups. California Route 299 leads to this location, east of Redding, through Burney Falls, near the volcanic strongholds of Mounts Shasta and Lassen, the latter with steaming geothermal deposits in Lassen National Volcanic Park.

A domain of stately evergreens breaks into a hot valley beyond Alturas with a little post office amidst the vast spaces. Ornaments made of local obsidian adorn the cool interior, where a cowboy and hired hand might sit eating. There are no tourists enjoying complimentary breakfasts; instead, the place has an air of rural purpose. My purpose was directions to the gem obsidian mine in the nearby mountains, and I began pressing the man in charge of digging permits for precise guidance until a grizzled local offered to take me to the mine.

Appreciating the View

We commenced by raising a path of dust along the first side road north of the post office, climbing two miles with no distinguishing markers. At a fork, my guide directed me left to follow the base of a mountain to an abrupt right turn, which led downhill over rattling bumps and shards of glinting obsidian dropped from mining trucks. A crystal stream lay at the bottom amidst stately evergreens that shaded the roadway until, a few hundred yards later, a log deliberately placed on a slope advertised a path uphill to the mine. Slightly further along, a metal gate denotes the official entrance to the diggings.

A path through the evergreen shadows over needles that were atypically straw-like for a conifer forest floor and highly flammable led to a bright opening where obsidian cascades down a steep slope like anthracite coal in the pure air. A lot of digging had been taking place. Had the gems been exhausted? Only the chance to break fresh ground could tell, but overburden from digging obscured the land downslope and left it virtually inaccessible.

Away from the diggings, which were under claim, I saw a huge relic of a conifer stump, with the host topsoil preserved beneath it and a flat rock overlaying several feet of untouched cobbles. Dirt covered the cobbles, giving them an ordinary appearance that only a sharp blow with the pick converted into shiny volcanic glass would unveil. Thus, I started to swing the pick.

My pick shattered a cobble that turned blackberry-purple in the light, bonding me with our planet in a way not available anywhere else. Though my pick blade soon bent into a flat bar as it struck the hard cobbles, I happily continued excavating as the wind sighed through the evergreens and I wondered at the reason why the earth yielded this color here, and only here.

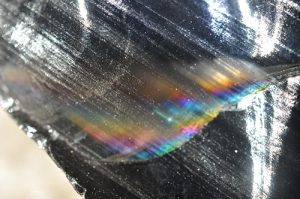

Rainbow Obsidian Hues

After each fresh breaking of a cobble, I held the stone with the sun at my back. The rays picked out an array of colors that followed the configuration of the obsidian, with ridges and jointures featuring sheens and rainbows of color. The sheen, often associated with wavy ridges, could be blue, green, pink, or purple, and the rainbows associated with the jointures were unconventional spectrums of vivid hues, the colors out of school-book order. Depending on the structure of the piece, both rainbows and sheen might appear.

Out of self-preservation, I wore glasses to prevent obsidian slivers from entering my eyes. Obsidian is one of the sharpest substances known. It actually outperforms surgical steel in medical procedures involving tiny cells where extreme delicacy is required.

Both Lake County diamonds and rainbow obsidian formed in the flowing glass factories of volcanic lava, but their differing composition produced unique gems. The silicon dioxide that produces the clarity of these gems approaches 100% purity, while that which formed the obsidian might fall as low as 70%. The makeup of rainbow obsidian includes magnetite crystals, which strike other internal rock fragments and disperse a wide range of colors depending on whether the stone is configured or flat.

Each piece was a gem, and I wanted to avoid having the TSA people at the airport consigning them to a luggage bag. I decided to ship them home instead. As I walked over to a UPS store in Chico, ash from the Mendocino Fire drifted down. The associate carefully packed my obsidian stones in a separate wrap, recognizing their value. She recounted finding a wave-smoothed obsidian pebble along Lake Shasta, and I again realized how volcanoes penetrate California culture.

Inspired Spirit to Hunt for Lake County Diamonds

A couple of months after my obsidian arrived home, something stirred me to revive my hunt for Lake County diamonds. I returned in October, the grape vines bereft of fruit. The vineyard foliage was russet-gold. Saffron oak and lemon walnut leaves lined the roadside where I walked along again, possessed with the compulsion to find a large specimen.

Within a few moments, I saw a half-inch specimen lying in plain view, kicked up by a driver’s tires, giving me relief from the wanderlust that instigated the trip. I followed the road further and saw a plump quarter-inch one. At one point, California ground squirrels had excavated the roadside, dredging up tiny Lake County diamonds. I was grateful that the road hadn’t yet been paved over.

This volcanic dirt supported mile upon mile of grape arbors and contributed to a commendable rearrangement of the landscape. The vintners unearthed huge boulders and placed them as decorative barriers along the roadside while retaining ponderosa pines to offset the harsh summer light of open grape rows, which stretched in geometric precision.

Picking up Lake County diamonds while wandering back roads ties together geology and culture, but one vineyard, in particular, offers a more direct portal into the relationship. The Sigma Six Ranch provides maybe the classiest rockhounding experience in the country with a tour that combines countryside, scenery, and a diamond-hunting venture.

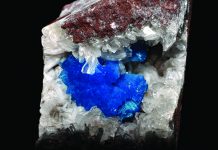

Weathering From the Matrix

The ranch memorializes the unique geography with a reddish basalt boulder encrusted with this Lake County natural treasure. Positioned outside the historic Stage Coach Stop Tasting Room, the rock shows the volcanic origin of the gems and how weathering from the hard matrix leaves them lying as singular gems throughout vineyards and along dirt roads.

To hunt “diamonds” on the ranch, book the Pinzgauer Vineyard Tour, a ride on an ATV that includes a stop at the Diamond Vineyard. This vineyard sits at a high elevation, 1,700 feet, where rains erode the earth and expose the gems. Christian Ahlmann, vice president of operations at Sigma Six, says that the Lake County diamonds there feature the known color variations, as well as blue.

Ms. Ahlmann explains that the young volcanic soil in the Diamond Vineyard has not weathered sufficiently to offer much nutrition to the vines. This lack of nutrition stresses the plants, which produce a glass of excellent red wine. They call it Six Sigma Diamond Mine Red Blend.

Six Sigma books reserved tours on Saturdays at 10 a.m., noon and 2 p.m., as well as private tours throughout the week. On a typical hunt, guests disembark from the ATV and spend 10 or 15 minutes hunting. From October through April, the rains expose stones that range to dime-size. They are distributed freely and don’t require a lengthy search.

Lake County diamonds originated during eruptions of nearby Mount Konocti, a local landmark overlooking expansive Clear Lake. The accompanying lava flows occurred between 350,000 and 13,000 years in the past, but Mount Konocti bears an official high threat eruptive potential to this day.

Lake County Diamonds – A Culture of Collecting

Adjacent Clear Lake is the oldest lake in America, at nearly 500,000 years; and at over 43,000 acres, the largest lake entirely within California. A long-held belief is that the magma chamber that yielded the “diamonds” extends into the body of the lake itself.

The sun shone on my large specimen and produced pink and blue points of light that my memory recognized from diamond rings. Such similarity has led to countless specimens faceted and worn.

This story about Lake County diamonds previously appeared in Rock & Gem magazine. Story by Bill Rozday. Click here to subscribe.