For centuries, pearls have been revered as treasures of the ocean—organic gemstones formed not by the Earth’s crust but by living creatures in the sea. Unlike crystals or minerals, pearls are biogenic gems, born from mollusks such as oysters, abalone, and even certain snails. Their luminous surfaces and extraordinary rarity have fascinated royals, jewelers, and collectors alike. But for rockhounds and lapidaries, pearls hold a different kind of intrigue: they represent nature’s artistry, an organic response to imperfection that becomes one of the most coveted jewels in the world.

Today, cultured pearls are common, but the rarest varieties—those formed under exceptional conditions—remain true “secrets of the sea.” From iridescent abalone to flame-patterned conch, these unusual gems are prized by gemologists and collectors. Before diving into the rarest of the rare, it helps to understand how are pearls made and what sets them apart in the gemstone world.

What Makes a Pearl Rare?

Pearls begin their life when an irritant enters a mollusk and the creature responds by coating it with layers of nacre, the same substance that forms the shell’s inner lining. Their scarcity and desirability aren’t just about beauty, they’re also about value. The market for pearls varies dramatically, and gemologists often look to factors such as size, luster, shape, and species to determine how much pearls are worth.

Unlike minerals that can be mined systematically, pearls rely on chance, each one a product of biology, environment, and time. For collectors, this unpredictability makes them as thrilling to study and acquire as any fine crystal or rare mineral specimen.

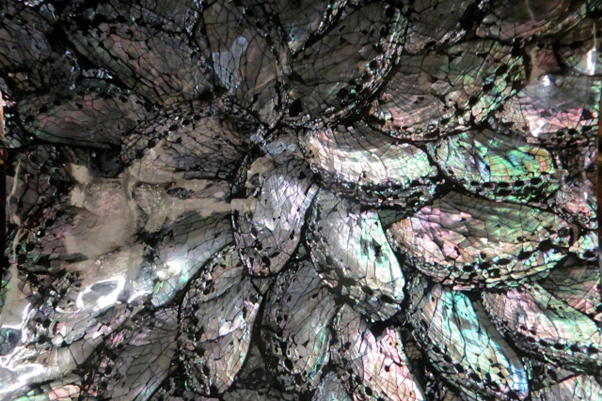

Abalone Pearls: Iridescent Rarities

Few pearls capture the imagination like abalone pearls. Produced by marine snails found along the coasts of California, New Zealand, and Japan, these gems shimmer with an unparalleled range of colors: electric blues, greens, purples, and fiery reds. Their nacre exhibits an intense iridescence caused by microscopic layers scattering light, the same effect that makes mother of pearl so captivating.

Unlike spherical pearls, abalone pearls are typically baroque in shape, reflecting the asymmetry of the shell itself. This makes them prized by collectors not just for their rarity but also for their individuality. Gemologists estimate that only one in several hundred thousand abalones may produce a pearl, making natural finds extremely valuable.

For lapidaries, abalone pearls present a challenge: they are fragile, thin, and often irregular. But when preserved intact, they represent some of the most spectacular organic gems ever discovered.

Conch Pearls: Caribbean Flames

While oysters dominate most pearl discussions, the queen conch (Strombus gigas) produces one of the ocean’s rarest treasures. Found in the Caribbean and parts of the Gulf of Mexico, conch pearls are non-nacreous, meaning they lack the iridescent surface associated with oysters. Instead, they exhibit a unique flame-like structure that creates a shimmering, silky effect across shades of pink, peach, and cream.

Conch pearls cannot be cultured—each one is a natural occurrence, discovered only by chance while harvesting conch for food. Their scarcity, combined with their unusual appearance, has made them a favorite of collectors and high jewelry houses alike.

Melo Melo Pearls: Golden Heat

Native to the waters of Southeast Asia, the Melo Melo sea snail (Melo melo) occasionally produces pearls in shades of vibrant orange, tan, or yellow. Like conch pearls, they are non-nacreous, their beauty derived from their porcelain-like surface rather than layers of nacre.

Melo pearls are typically large, sometimes exceeding the size of a golf ball, and their bold hues make them standouts in any collection. Their rarity is legendary; entire fishing communities may never encounter one in decades of harvesting. For gem collectors, finding a Melo Melo pearl is akin to discovering a perfectly terminated crystal in a rough vein: a once-in-a-lifetime event.

Natural Pearls: History’s Hidden Treasures

Before the advent of cultured pearl farming in the early 20th century, all pearls were natural. Divers risked their lives searching oyster beds in the Persian Gulf, the Indian Ocean, and the coasts of Japan. These pearls were traded along the Silk Road, gifted to royalty, and enshrined in museums.

Today, natural pearls are nearly extinct in the market. Overfishing, pollution, and habitat loss mean very few wild oysters produce pearls of significant quality. Collectors who own natural strands or single specimens hold pieces of history as much as jewelry. The extreme rarity of natural pearls has driven their value higher than many mined gemstones.

Freshwater and Cultured Pearls: The Accessible Alternative

Most pearls available today are cultured, meaning they are intentionally grown by introducing an irritant into an oyster or mussel. Freshwater pearls, cultivated primarily in China, are the most abundant. They vary widely in shape and color, offering affordability without sacrificing beauty.

For collectors and jewelers, cultured pearls provide a way to enjoy these organic gems without depleting wild populations. Still, the rare natural varieties—conch, Melo Melo, abalone—remain the holy grail of pearl collecting.

South Sea Pearls: Ocean Giants

Among cultured pearls, South Sea pearls are considered the most luxurious. Harvested in the waters off Australia, Indonesia, and the Philippines, they are prized for their large sizes (often over 15mm) and their satiny luster. These pearls form in the Pinctada Maxima oyster, which itself can reach the size of a dinner plate.

South Sea pearls come in both golden and white varieties. The golden pearls, especially those with deep hues, command exceptional prices. While Rock & Gem will feature a dedicated article on South Sea pearls in 2026, they deserve a mention here as one of the ocean’s most coveted cultured gems.

Why Rockhounds Care About Pearls

At first glance, pearls may seem separate from the mineral specimens prized by rockhounds. They lack crystal structure, form in living organisms, and can’t be faceted in the traditional sense. Yet they belong in the broader world of gemology as organic gemstones, alongside amber, jet, and coral.

For lapidaries, pearls are intriguing precisely because of this difference. They demonstrate nature’s ability to create beauty through biology rather than geology. They also connect to human culture in ways few gemstones do, from ancient mythology to modern red carpet trends. Collectors may prize them not just for their aesthetic, but for the remarkable story of their formation and discovery.

Final Thoughts

Pearls are more than jewelry: they are natural marvels of biology, rarity, and beauty. The rarest examples, like abalone, conch, Melo Melo, and natural wild pearls, capture the imagination of both jewelers and rockhounds. They remind us that the ocean still holds mysteries, treasures formed in darkness and pressure, waiting to be revealed.

For collectors, pearls represent the intersection of nature’s chance and human desire, proof that the secrets of the sea remain some of the most coveted gems on Earth.

This story was written for Rock & Gem magazine by the Pearl Source. Click here to subscribe to Rock & Gem magazine.