Indonesian grape agate comes from the city of Mamuju, on the island of West Sulawesi, hours away from any adjacent villages. This material is difficult to retrieve as the trek there can only be done on foot. Through valleys, rivers and the threat of wild animals, the challenge to obtain such material can only be compared to its beauty.

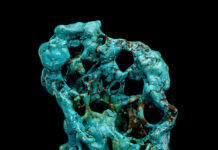

Formed under ancient volcanic activity, grape agate is found in botryoidal clusters embedded within blue/grey clay and andesite-origin rock. Growing in lava gas bubbles, mineral-rich silica settles and forms to look like bundles of grapes. Most consistently botryoidal in appearance, grape agate displays colors from a light lilac to a deeper amethyst, even uncommon blue/greens, too. Its purple hues are colored by minerals like manganese, whereas traces of celadonite give its blue/green colors. Additionally, it’s important to note that the name “grape agate” is not fully consistent with the stone itself. Agate is a little misleading, as it is mostly quartz and/or chalcedony in nature. Grape agate is just too memorable a name!

How to Find Indonesian Grape Agate

Grape agate was found around 2014 to 2016 and has since been a spectacle at many trade shows and online marketplaces. When purchasing this material, the best thing you can do is observe. Its most enticing and telltale features are those of the surface. Some will appear duller in appearance or show a rougher botryoidal surface. Others will have a deeper color, stronger botryoidal formations, and even druzy covering it head to toe. Oftentimes, it can be quite pricey, so it’s best to know what you’re looking for and what to expect.

Slabbing Grape Agate

Slabbing Grape Agate

Most of the time, they’re available uncut, leaving you with the task of slabbing. This can be tricky depending on your desired outcome. If you choose to cut against the botryoidal surface, be careful not to slab too closely to the botryoidal surface. Often these spherules tend to break off one by one or in small clusters. To minimize this, I cut perpendicular to the surface with enough space, so it stays together. Then, once I’ve identified my potential preforms, I cut them out and slice the back as thin as I am comfortable cutting. Then, I’m ready to start cabbing.

Many people, however, choose to use only the internal material because of its delicate nature. Being mostly uniform throughout, no one direction will yield a better pattern. Once cut, be sure to examine and bench test the slabs for cabbing. Though mostly solid internally, it can have a few natural fractures. It’s better to have it break early in the process. Once you know about these pitfalls, you’re ready to start cabbing.

Cabbing Techniques for Indonesian Grape Agate

Cabbing Techniques for Indonesian Grape Agate

The cabbing process can be a bit tricky. If you plan to incorporate the botryoidal edges into your designs, use a softer touch to minimize the chance of chipped edges. Keeping slow and steady, I start on the 80-grit steel diamond wheel and slowly work out my preferred shapes. Use gentle pressure when working around your outline to reduce the chance of popping orbs and chipped edges. Only work your stone as much as necessary before moving on. At this point, I like moving directly to a soft rein wheel, either 60 or 140-grit to smooth out and form the dome. By this stage, you should have most of your harshest scratches worked out.

Finishing Your Agate Cabochon

Make your way to the 280-grit stage next. It’s always important to check your work by stopping to dry off your cab, checking for any scratches, and backing up until you’re ready to move forward. From here, the final steps become more routine. By the 600-grit wheel, you should no longer see any remaining micro scratches and see a soft shine starting to form. Then, follow through with your preferred polishing wheels until you are happy. I opt to stop at the 14k wheel, but if you want to go further and gain an extra glossy shine, you can use Zam polishing compound on a Dremel tool with a soft felt tip.

Grape Agate FAQ

Q: What is Indonesian grape agate?

A: Indonesian grape agate is a botryoidal mineral formation mostly composed of quartz and chalcedony. It forms in volcanic regions of West Sulawesi, Indonesia, and is named for its grape-like clusters. Its colors range from light lilac to deep purple, with occasional blue or green hues.

Q: Where is Indonesian grape agate found?

A: It is primarily found near Mamuju, West Sulawesi, Indonesia. Access to these deposits is challenging and requires trekking on foot through valleys, rivers, and rough terrain.

Q: How is Indonesian grape agate formed?

A: Grape agate forms in lava gas bubbles when silica-rich minerals settle over time. The botryoidal (grape-like) structure develops as layers of mineral deposits build up, sometimes enriched with manganese or celadonite for color variations.

Q: How do you slab Indonesian grape agate?

A: When slabbing, cut perpendicular to the botryoidal surface, leaving space to prevent the spherical clusters from breaking. Identify potential preforms first and slice carefully to preserve the integrity of the stone.

Q: How do you cab Indonesian grape agate?

A: Start with an 80-grit diamond wheel and work slowly around the stone’s edges. Gentle pressure and slow progression help protect the botryoidal formations. Move through finer grits gradually, finishing with a polishing wheel or Zam compound for a glossy shine.

Q: How do you identify high-quality Indonesian grape agate?

A: Look for deep, consistent color, strong botryoidal formations, and minimal surface roughness. Druzy coverage can also indicate premium material, but internal fractures should be checked during bench testing.

Q: Is Indonesian grape agate expensive?

A: Prices vary depending on color, size, and quality. High-quality specimens with deep color and intact botryoidal formations can be quite costly.

This story about Indonesian grape agate was written for Rock & Gem magazine. Click here to subscribe. Story and photos by Ben Kaniuth.