Story by Bob Jones

One of the most unusual collections of crystallized gold is in a glass-fronted vault of the Coors Gems and Mineral Hall, in the Denver Museum of Nature and Science. Found on Farncomb Hill, near Breckenridge, the gold is beautifully crystallized, with many sections showing an odd and sometimes rhombic form of a carbonate deposit where it crystallized.

The Farncomb Hill crystallized gold in the museum collection contains choice examples of free-standing thin gold septa and leaf-forms covered with sparkling, tiny gold octahedrons. Some of the leaf forms are up to four and five inches high and two inches wide and only a fraction of an inch thick. The septa of many specimens have developed in box-like forms as the gold-bearing solutions followed the normal rhombic cleavage planes of a carbonate mineral in which they crystallized.

Farncomb Hill’s Formation

Farncomb Hill is a quartz monazite structure overlain with cretaceous shale and limonitic slippage zones. The gold-bearing hydrothermal solutions invaded and crystallized in carbonate gouge slippage zones. The carbonate was most likely siderite, an iron carbonate mineral as rust on specimens is common. Scientists estimate the formations on Farncomb Hill date back some 100 million years, a relatively young age as gold deposits go.

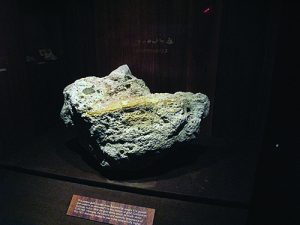

Crustal pressures force gold-bearing hydrothermal solutions into openings in the gouge-filled slippage zones. As the solution cools, the gold crystallizes taking the shape of the cleavage plane opening in the gouge. Later weathering decomposed the siderite and coated everything with iron oxide rust. Evidence of this is obvious on the huge flaky gold specimen called Tom’s Baby, Colorado’s largest gold nugget.

Crustal pressures force gold-bearing hydrothermal solutions into openings in the gouge-filled slippage zones. As the solution cools, the gold crystallizes taking the shape of the cleavage plane opening in the gouge. Later weathering decomposed the siderite and coated everything with iron oxide rust. Evidence of this is obvious on the huge flaky gold specimen called Tom’s Baby, Colorado’s largest gold nugget.

With the discovery of gold on Clear Creek west of Denver in 1859, the rush to Colorado’s interior started. Prospectors breached the Front Range of the Rockies and panned every creek and gulch. This search brought the Weaver Brothers into the Blue River area near today’s town of Breckenridge, which rests among abandoned gold dredge gravel piles.

Prospectors worked all the tributaries and gulches off the Blue River, including the American, French, and Humbug gulches with some success.

This writer, in the 1980s, tried his hand on French Creek, but it had been picked clean. My family had rented a place in Breckenridge for a month a couple of times, and we enjoyed tracking down the old mines, climbing on the abandoned gold dredges and horseback riding high above the treeline on Tenmile Range. But, in the 1880s, gold prospecting was the serious business around Breckenridge.

Farncomb’s Legendary Discoveries

One such prospector was Henry Farncomb, who worked the Blue River area. His discovery paid off in 1878 when Henry hit an amazing alluvial deposit of gold. Instead of flakes and tiny nuggets of the creek bed, Francomb found large tangled masses of wire gold. One mass he found weighed 11 pounds. He named his alluvial claim the Wire Patch. By tracing this floating gold uphill, he found the hard rock source of the wire gold and opened the Wire Patch Mine. Later the gold-rich hill was named for Henry Farncomb.

One of the more interesting facts about Farncomb Hill deposits is how shallow they

DENVER MUSEUM OF NATURE AND SCIENCE

were. Today it is not unusual for a mine to reach several thousand feet into the earth. I’ve personally been as deep as 4,800 feet in a copper mine. The South African gold mine shafts reach over a mile deep. The mines on Farncomb Hill seldom exceeded 500 feet into the bowels of the hill. Glaciers had scoured away much of the gold-bearing carbonate rocks and deposited the rock debris in the river valley. Who knows how many feet of the surface riches were removed before the 1880s discoveries. The result was gravel in the river bottom and gold-bearing gravels to a depth of 90 feet to bedrock.

As gold discoveries in Colorado go, the discoveries in the Breckenridge area were latecomers. All the early finds elsewhere in the state date to 1859. But once found, gold on Farncomb Hill produced some of the state’s most amazing crystallized septa and leaf gold so we can enjoy it in the Denver Museum of Nature and Science.

This writer thanks, now retired Museum Curator Jack Murphy, who gave us an opportunity to visit the museum many years ago and gently handle and photograph the gold for Rock & Gem. We had arranged to visit the museum when Jack was going to clean the gold display vault after closing.

This has to be done regularly as the lovely background cloth becomes dusty and even has an occasional flake of gold fall off specimens, due to vibrations in the hall. As Jack removed specimens so he could clean them and the display vault, I was allowed to set up by his work table and get photographs.

Inspiring Rockhounding Appreciation In Next Generation

My son Evan was a young teenager at the time and accompanied me during the photo session. At one point during the cleaning session, Jack handed Evan a small cloth bag and suggested he look at its contents. Evan untied the drawstring, reached in, and pulled out a lovely one pound gold nugget, Colorado’s largest nugget.

Every museum gold collection has stories and tales. The Denver’s museum collection is no exception. It is largely the property of one person, John Campion, who, like Harvard’s A. C. Burrage was a lover of crystallized gold.

DENVER MUSEUM OF NATURE AND SCIENCE

Campion was in a perfect position to acquire Breckenridge gold. He was one of the owners of mines on Farncomb Hill, including the productive Wapiti mine. He also owned rich mines in Leadville, including the Little Johnny, now Ibex mine. Campion was nicknamed “Little Johnny,” but I don’t know which came first, his nickname or the name of the mine. He was one of Colorado’s richest mine owners, and in later life, he became a board member of the Denver Museum. It was inevitable that his collection of Breckenridge gold would be donated there.

Some of the gold deposits, lower at the base of Farncomb Hill, were below the overlying carbonaceous shale, so gold was found in more traditional quartz veins. But mines further up the hill produced the oddly shaped unusual crystallized gold. One such mine was the Gold Flake mine, whose name tells you what the gold was like. The Gold Flake, in those early days, was not worked by the owner but by contract miners who worked for a share of the take. That method is still in use today.

The Story of Tom’s Baby

A highlight in the mine’s history took place when two contract miners, Tom Groves and Harry Lytton, were working the Gold Flake mine at a relatively shallow depth when they hit a huge gold pocket that astounded them. Keep in mind that some of Farncomb Hill’s gold-bearing pockets were as much as two to three feet wide and lined with crystallized gold. When Groves and Lytton hit their big pocket, they were doubly amazed because the gold-lined cavity also had a huge mass of gold loose in the bottom of the pocket. Later, when weighed in, the assayer’s office said it was 13 and a half pounds! It took the men over four hours to carefully extract this golden beauty, which was not quite so beautiful, for it was covered with rust.

The miners carried their find to town wrapped in a blanket, hence the name Tom’s baby. They headed for the assayer’s office to weigh it and determine the value, which would determine their percent of pay. It also needed cleaning, so the assayer immersed the piece in acid to remove unwanted minerals. Once out of the acid bath, the piece was weighed again and found to have lost some weight. A small piece or two of gold fell off during the cleaning process.

Once the piece was clean and weighed, now a reported nine and a half pounds, the men

JAMES ST. JOHN, WIKIMEDIA COMMONS

turned it over to the mine owner, who planned to ship it to Denver. Legend states the piece disappeared en route, but there is plenty of evidence it was displayed off and on ending up in the Denver Museum where it was exhibited in 1930. I should point out that the Gold Flake mine, the source of Tom’s Baby, was part of the Wapiti Group of mines, owned by Campion, who gave his collection of Breckenridge gold to the Denver Museum of Nature and Science. It is not inconceivable that he ended up owning Tom’s Baby early on.

Another mystery surrounds Tom’s Baby. It seems to have disappeared for certain, sometime after the 1930 museum viewing. There is no record of what happened. However, one speculation is that during World War II, the museum staff may have put things in a bank vault for safekeeping. What we do know is how and why Tom’s Baby was re-discovered in 1972.

Remember when I mentioned Jack Murphy, who made it possible for me to photograph the Campion gold collection? When Jack was hired and became the curator of the museum’s mineral collection, he requested the collection be inventoried, a good idea just to protect everyone. While the inventory was being conducted, a member of the museum’s Board of Directors asked if they were going to inventory the goods stored in the vault of the United Bank, in Denver. What goods? What bank? The staff at the museum knew nothing about this vault storage. There was no record of anything being stored at the bank.

Uncovering Unexpected Treasures

So, Jack, author Mark Fiester and museum staff hiked down to the bank, and sure enough, there was a crate in the vault marked “Property of the Museum.” When opened, one of the first items that showed up was a huge chunk of gold, which the author Meister immediately recognized as Tom’s Baby. He realized what was before them, because he had researched Breckenridge gold, and subsequently wrote a fine book, Blasted, Beloved Breckenridge, which I found delightful reading.

Tom’s Baby had been broken in two and lost a bit of weight, having shrunk from its original thirteen and a half pounds to a little over eight pounds (103 ounces), which is what is displayed today. Visitors to the museum can see where the repaired breakage occurred. As you read other sources about Tom’s Baby, you will come across various weights given. The current 103 ounces is accurate.

This concludes our three-part series on gold. In addition to this exploration of some of the finest and most interesting examples of crystallized gold in the Denver Museum of Nature and Science, in part one of this series (January 2020 issue), we discussed the fascinating gold specimens in the museum at Harvard University, Cambridge Massachusetts. In part two of the series (February 2020 issue), we introduced you to the amazing 2018 Father’s Day discovery of gold in quartz, in the Beta Hunt mine, Australia. It is rumored that this working nickel-gold mine expects to encounter more specimen gold as it continues its operations.

Rest assured, Rock & Gem will report on any future exciting finds that happen Down Under, stateside, and in many other parts of the world.