After 20 years of work, Georgius Agricola completed the text of De Re Metallica in 1550. Incorporating information from his earlier works, it consisted of “12 books” (chapters) that covered all aspects of early Renaissance prospecting, mining, assaying, and smelting. His opening arguments are familiar today. While admitting that mining can be environmentally degrading, he justifies the industry because metals provide ever-increasing societal benefits.

Note: To enjoy the first part of this fascinating study of this transformative reference, click this link.

Georgius Agricola demonstrated a concern for mining health and safety that was far ahead of his time. As a physician, he realized that underground dust and smoke caused serious lung issues, writing that…“Stagnant air … produces a difficulty in breathing; the remedies for this evil are the ventilating machines I have described.” Acknowledging the inherent dangers of underground mining, he believed that safety is the management’s responsibility and alluded to the need for safety inspections and training.

Advice for Mine Owners

As a shareholder in St. Joachimsthal’s hugely profitable Gottsgaab (God’s Gift) silver mine, Georgius Agricola offers thoughtful tips to hopeful mining investors, advising them to beware of fraud and to investigate mines personally. He advises prospectors who have found surface indications of mineralization to dig systematic trenches to reveal the veins, then describes the many vein configurations. Discounting the medieval belief that placer gold is generated in the gravels of river beds, he explains instead that it is washed by water from nearby veins.

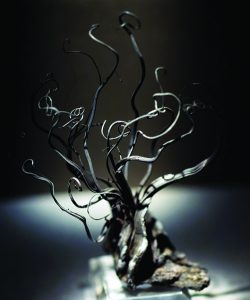

Although a pioneer in scientific thinking, Agricola did retain a few medieval concepts. He failed to recognize fossilized marine shells as the remains of living creatures, describing them instead as materia pinguis or “fatty matter” that had been “fermented” and shaped by heat. While generally discrediting the supernatural, Agricola, like virtually all miners of his time, believed that gnomes inhabited the underground mines. He wrote of “good” gnomes who help miners and “bad” gnomes who caused trouble, injury, and even death and advised “fasting and praying” to thwart the latter. Interestingly, the idea of gnomes persisted into the 19th century, when some miners in England and the United States still believed in “tommyknockers.”

Mountain Masters

Particularly interesting is Agricola’s account of how Bergmeistern (“mountain masters”) control mining activity and, following new mineral discoveries, divide the land into orderly leases—a rudiment of the mineral-claim system later employed in the United States. Taking the reader underground, Georgius Agricola describes shafts, tunnels, and timbering, along with ore haulage, pumping, surveying, and ventilating equipment. In an era that preceded the introduction of drilling and blasting, he explains the ancient and dangerous method of using fire to break hard rock and how miners would exploit the resulting thermal-stress cracks using hammers and wedges.

Georgius Agricola relates how miners, with no knowledge of chemistry, identify metal ores by color. Probably from his own experience as a Gottsgaab mine investor, he notes that the richest Erzgebirge silver ores graded, in modern terms, more than 700 troy ounces per ton. Turning to the world of 16th-century metallurgy, Agricola describes assaying techniques and equipment, the arithmetic conversion of assay results to ore grades, techniques of separating metals, amalgamation, ore sorting and crushing, smelting furnaces and fluxes, slag removal, and the pouring of molten metals.

De Re Metallica concludes with accounts of the preparation of the era’s industrial chemicals—salt, soda (sodium carbonate), niter (sodium nitrate), alum (potassium aluminum sulfate), vitriol (iron sulfate), saltpeter (potassium nitrate), sulfur, bitumen (petroleum, tar) and glass.

Sketches for Posterity

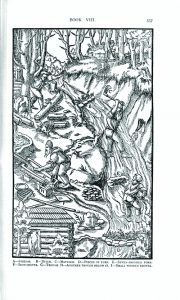

After completing the text, Agricola was concerned that his words “should either not be understood by men of our own times or cause problems to posterity,” and commissioned artists to create 273 sketches to illustrate specific aspects of his text.

In 1553, he sent these sketches to a printer in Basel, Switzerland, who prepared woodcuts from blocks of soft wood sawed lengthwise along the grain and planed smooth. Engravers then copied the illustrations onto the wooden blocks and engraved them with knives and chisels. Engravers cut two parallel grooves, leaving a narrow ridge between the lines, then reduced all surrounding areas to form raised lines that would take the ink. The finished woodcuts were mirrored images of the illustrations to ensure they would print correctly.

Publication of a major work like De Re Metallica pushed the limits of 16th-century printing technology. Engraving the 273 woodcuts took two years, after which the text was set in moveable metal type, at that time a relatively new technology.

After Publication

Georgius Agricola did not live to see his legendary work in print. The book was published in 1556, just months after his death the previous year. A few years later, it was reprinted in Latin, Italian, and German. In 1643, much of the book was translated into, and published in Chinese. De Re Metallica would remain the world’s premier work on mining and metallurgy for the next 200 years. Shortly after its publication, huge volumes of silver began pouring into Europe from Spain’s colonial mines in Peru and Mexico. Although the Erzgebirge mines’ importance declined, mining continued there at a much slower pace until the 20th century.

Today, the Erzgebirge relies heavily on tourism and offers visitors more than 30 underground mine tours and mining museums. In 2019, in recognition of its long mining history and rich heritage, the United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) listed the Erzgebirge as a World Heritage Site.

A Presidential Connection

Although Erzgebirge metal mining has finally ended, the book it inspired lives on. In 1912, the book was translated into English by Herbert Clark Hoover and his wife Lou Henry Hoover, who would serve as President and First Lady of the United States from 1929 to 1933. Hoover had graduated from Stanford University in 1895 as a mining engineer, while Lou Henry had graduated from Stanford in 1898 as the first American woman to earn a degree in geology. After marrying in 1899, the couple traveled the world together as Herbert became an internationally renowned mining engineer and Lou became proficient in five languages, including Latin.

The Hoovers began translating De Re Metallica from Latin into English in 1908. When Agricola wrote his original text, the Latin language had not been expanded in 1,000 years. Rather than express numerous new technical and geological concepts in his native German, Agricola instead coined hundreds of new Latin expressions, presenting the Hoovers with the difficult task of deciphering his unique Latin terminology. Not only did the Hoovers do an exceptional job of translating, but they also added explanatory introductions and extensive footnotes, providing invaluable modern and historical perspectives that are no less interesting than Agricola’s text itself.

Herbert Hoover’s Translation

The 1912 Hoover translation of this storied resource was published as a run of 1,780 hardcover books. Today, these are collectors’ items that sell for about $1,000 per copy. Fine copies of the original, 1556 Latin edition sell for more than $100,000. Dover Publications reprinted the Hoover translation in 1950. Today, this translation is still affordable, widely circulated, and available through libraries.

Herbert Hoover described Georgius Agricola as “the first to found any of the natural sciences upon research and observation rather than the previous fruitless speculation.” Today, Agricola’s work remains a benchmark in the story of scientific advancement and mining history. Representing the dawn of mining engineering, geology, and mineralogy, it is a fascinating window into mining and metallurgy as it existed almost 500 years ago.

A final exciting bit of news surrounding this timeless text is that the entire 1912 De Re Metallica translation, including the original illustrations and the Hoover preface, introduction, footnotes, annotations, and index, is available free for download at www.gutenberg.org. Simply enter De Re Metallica in the search field, and you’ll receive multiple options for accessing the text.

This article about Georgius Agricola and De Re Metallica previously appeared in Rock & Gem magazine. Click here to subscribe. Story by Steve Voynick.