The Great Sand Dunes National Park, with its centerpiece 30-square-mile dunefield, is part of the greatest concentration of sand dunes on the North American continent all located in the Southwest. Many of these are national parks and monuments, state parks, or recreational areas that are managed by the Federal Bureau of Land Management. Together, they attract millions of visitors each year.

Unique Southwest Dunefields

None of the Southwest’s dunefields are alike. New Mexico’s White Sands National Monument is famed for its glistening, white dunes of pure gypsum, while the dunes of Utah’s Coral Pink Sand Dunes State Park consist of distinctively colored, reddish sand derived from Navajo Sandstone. Some dunefields are only a few square miles in area, while California’s Algodones Dunes, the largest in the nation, cover 300 square miles.

Great Sand’s Dunefield

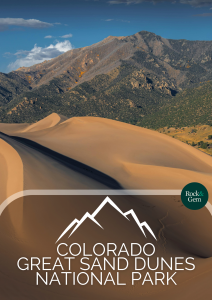

One of the best-known of these dunefields is in Colorado’s Great Sand Dunes National Park and Preserve. Its namesake attraction is the Great Sand Dunes—a 33-square-mile deposit of dramatically sculpted sand that is nearly devoid of vegetation. This dunefield is crowned by the continent’s tallest dune—Star Dune, which soars 755 feet from base to crest. And nestled at the base of a range of 14,000-foot-high peaks, the Great Sand Dunes are unmatched for scenic splendor.

But the Great Sand Dunes is far more than spectacular scenery. Constantly migrating, eroding and rebuilding, these dunes are a place where geology comes alive, where legends thrive, and where plain old sand takes on a whole new perspective.

Great Sand Dunes National Park and Preserve is located 30 miles northeast of Alamosa at the eastern edge of south-central Colorado’s sprawling San Luis Valley. Visible on clear days from a distance of nearly 50 miles, the dunes have long served as a regional landmark for Native Americans, explorers and settlers.

The San Luis Valley is bounded on the east by the fault-block Sangre de Cristo Mountains and on the west by the volcanic San Juan Mountains. The valley itself is part of the north-south-trending Great American Rift. This geologic rift began forming some 25 million years ago after tectonically driven crustal stretching enabled huge blocks of crust between two parallel fault systems to slowly subside more than 10,000 feet, creating a rift valley.

Impact of Natural Transitions

Over eons, the cumulative effects of temperature extremes, rain, snowmelt, wind, and alpine glaciation eroded both the Sangre de Cristo and San Juan mountains, producing huge volumes of silt, sand and gravel that filled the valley floor to its current elevation of 8,000 feet. During the geologically recent Pleistocene ice ages, much of the San Luis Valley was covered by ancient Lake Alamosa.

About 20,000 years ago, two events set the stage for the creation of the Great Sand Dunes. First, alpine glaciation scoured a pair of low passes in the crest of the Sangre de Cristo Mountains; second, as the climate became warmer and more arid, Lake Alamosa disappeared, exposing its vast bed of sand and silt to wind erosion.

Although often used generically, the terms “sand” and “silt” have precise geological definitions. Sand is a naturally occurring, granular material composed of finely divided particles of rocks and minerals that range in size from 0.06 mm to 2 mm (0.002 to 0.08 inches). Anything smaller is classified as silt; anything larger is classified as gravel. Some rockhounds called psammophiles collect the small minerals that make up sand.

The prevailing southwesterly winds that swept this dry lakebed carried enormous quantities of sand and silt to the northeast. Upon reaching the Sangre de Cristo Mountains, the winds were forced upward and funneled through the two mountain passes. The winds carried airborne silt through the passes, but dropped the larger and heavier sand particles at the base of the mountains, where they accumulated as a dunefield.

Worn by Wind

Had these prevailing southwest winds remained steady throughout the year, geologists believe that all the sand would have eventually moved eastward over the Sangre de Cristo Mountains. But in winter, powerful, reverse winds pushed the dunes backward in a “holding action” that kept the growing dunefield near, but not directly against, the mountain front.

In just 20,000 years—a blink of an eye in geologic time—the winds deposited some 5 billion cubic meters (1.2 cubic miles) of sand. The winds were also remarkably efficient in sizing or classifying the sand—virtually all the grains measure about 0.2 mm (0.008 inches) in diameter.

At the Great Sand Dunes, sand movement is caused by four distinct processes: suspension, saltation, creep and avalanche. Suspension, in which strong winds carry airborne sand grains for considerable distances, accounts for only 1% of total sand movement. About 95% of sand movement is due to saltation, a term stemming from the Latin saltare, meaning “to leap.” In saltation, wind-driven sand grains “bounce” an inch or so above the surface, while moving 2 to 4 inches forward. Creep occurs during saltation, when wind-driven sand strikes stationary grains to propel them forward.

Masses of sand move by avalanche. Sand dunes have gentle slopes on their windward, or erosional, sides, and much steeper slopes on their leeward sides.

When leeward-slope angles exceed 34% (the angle of repose or maximum angle of physical competence), avalanches occur as smooth flows of dry sand or massive “slumps” of wet sand. Avalanches are sometimes accompanied by eerie humming or moaning sounds, as air within the moving sand is compressed and released to produce audible vibrations.

The Great Sand Dunes National Park – Constantly In Motion

Through the combined effects of suspension, saltation, creep and avalanche, tall dunes at the Great Sand Dunes can migrate as far as 328 feet per year. The stronger, reverse winds of winter can move dune crests as far as 18 feet in a single day.

Even on the calmest days at Great Sand Dunes, the sand is always moving by saltation, creep, and tiny, gentle avalanches. These almost imperceptible movements are fittingly evoked in the lyrics of the western ballad Shifting, Whispering Sands…“You would think the sands are resting, / but you find this is not so.”

There are many different dune structures at the Great Sand Dunes National Park. Large, uniform movements of sand create massive, transverse dunes with more or less straight crests that are hundreds of feet long. Reversing dunes form when the reverse-direction winter winds halt the normal migration of transverse dunes and push sand backward to build crests taller than 700 feet. These giant dunes are also called star dunes because several crest ridges culminate at their summits in starlike patterns. This is the inspiration for the name of the Great Sand Dunes’ tallest dune—755-foot-high Star Dune.

Barchan (from the Arabic word for “ram’s horn”) dunes are shaped like crescents, with arms swept forward in the direction of movement. The mirror images of barchan dunes are parabolic dunes with arms that trail the direction of movement. Climbing dunes have irregular shapes and form when migrating dunes overtake obstacles, like trees or less-active dunes.

The Great Sand Dunes National Park – A Magnified View

Under magnification, sand from the Great Sand Dunes are seen as well-rounded grains, with smooth surfaces frosted by abrasion and collisions incurred during saltation, creep and avalanche. Roughly two-thirds of this sand originated as volcanic fragments from the San Juan Mountains; the remainder consists of particles of white-and-pink feldspar minerals and transparent, colorless quartz from the Sangre de Cristo Mountains. Also present in small amounts are two minerals that played an interesting role in the modern history of the dunes: magnetite and gold.

Archaeological evidence indicates that humans first visited the Great Sand Dunes about 12,000 years ago when the dunefield was still quite young. Spanish explorers passed near the dunes in the 1700s, while the first Americans saw the dunes in 1807. These were members of a United States Army exploration party led by Lt. Zebulon Pike, who described the dunefield as, “sandy hills … [whose] appearance was exactly that of the sea in storm, except as to color, and not the least sign of vegetation existing thereupon”.

In the 1850s, settlers began exploring the dunes, occasionally finding the remains of wagons and the bones of horses and humans. At the northeast edge of the dunefield, they came across an eerie forest of dead, 70-foot-tall Ponderosa pines that had been partially buried and killed by the advancing dunes.

Colorful legends inspired by the dunefield told of horses that grew webbed feet to gallop in the sand, entire towns that had been buried by migrating dunes, and even a Spanish oxcart laden with gold bars that occasionally appeared—only to be quickly reburied by the shifting sand.

Dunefields and Prospecting

In the late 1920s, prospectors turned their attention to the black sand that accumulated below the crests on the lee side of the dunes. The dark sand was magnetite, or magnetic iron oxide, that was concentrated by wind-driven (eolian) gravitational separation. As the wind blows sand over the dune crests, magnetite particles, which are twice as dense as the other sand minerals, fall quickly to collect in dark, horizontal streaks.

Gold Running “Flour” Gold

In the late 1920s, assays of this magnetite revealed the presence of fine particles of “flour” gold. After newspapers reported that “the sand has been tested and found to have in it gold running $3 to the ton”, prospectors quickly descended upon the dunes to hammer countless claim stakes, most of which were soon buried. Meanwhile, promoters began calculating the value of the gold waiting to be mined by multiplying the highest assay reports by wild guesses of the estimated tonnage of sand in the Great Sand Dunes. They concluded—and the press subsequently reported—that the dunes contained not millions, but billions of dollars in gold.

Although flour gold was difficult to recover, the Great Sand Dunes nevertheless seemed like a miner’s dream—there was no need to drill, blast, dig or pitch boulders; they could just start shoveling. And many miners did exactly that, setting up sluice boxes in Medano Creek, which flows along the northeast edge of the dunes.

Medano Creek helps to control the advance of the dunes by washing large volumes of sand back toward the southwest. With its porous, sandy bed, Medano Creek is a classic “disappearing river”. Fifty feet wide and a foot deep one day, it might be a mere trickle the next, or its braided channels might shift laterally 100 yards or more. Miners who returned to their claims for another day of work sometimes found their sluices washed away, buried, or far from the nearest water.

Protecting the Great Sand Dunes National Park

The most ambitious effort to mine the dunes came in 1929 when the Volcanic Mining Co. built a small mill along Medano Creek with shaker tables and amalgamation vats. But the fineness of the gold, together with grossly misinterpreted assay reports, meant failure was inevitable. Historians now believe that the gold assays of “$3 to the ton” referred not to a ton of sand, but to a ton of magnetite, which is only a minor component of the sand.

By the time the Volcanic Mining Co. built its mill, the Great Sand Dunes were already a popular tourist attraction that benefited Alamosa and other nearby communities. Fearing that the local gold rush would destroy the beauty and tourism potential of the dunes, San Luis Valley residents petitioned the federal government for help. Their work paid off in 1932 when President Herbert Hoover proclaimed the Great Sand Dunes a national monument.

How Much Gold Was in the Dunes?

Just how much gold is actually in the the Great Sand Dunes National Park was apparently answered in 1938, when a local miner developed an efficient and reliable extraction process that recovered 21 cents worth of gold (at $35 per troy ounce) from 2.5 tons of sand. These figures indicate a grade of 0.002 troy ounce per ton—less than that of the lowest-grade gold ores now being mass-mined in today’s huge open-pit mines.

During the Depression years, “soda miners” flocked to the sabkha, a salt-encrusted, sandy plain just west of the dunefield. The sabkha (an anglicization of an Arabic word for “salt flat”) is an area of ponds and marshes ringed with white crusts of carbonates and bicarbonates of sodium and potassium that precipitate as the alkaline water evaporates. The sabkha was the site of the short-lived settlement of Soda City, where residents gathered the evaporite minerals and pressed them into blocks for sale as laundry soap.

Preservation Reveals Origin Details

In 2002, the Great Sand Dunes National Monument was reorganized as Great Sand Dunes National Park and Preserve, with an expanded area of 234 square miles. Today, its visitor center, which welcomes some 300,000 visitors each year, offers a beautiful view of the dunefield, an introductory video, and many interactive exhibits.

The dune-access parking area is one mile north of the visitor center. To reach the dunes, visitors must first cross Medano Creek. During the spring snowmelt runoff, Medano Creek can be a foot deep and 50 yards wide; by late summer, it is sometimes completely dry.

Medano Creek

Medano Creek is one of the world’s few examples of a hydrological phenomenon called “surge flow.” When the creek is running high, sand swept along by the current accumulates in underwater ridges called “antidunes” which periodically dam up the water that creates them. Several times each minute, the building back-pressure of the current overcomes these antidunes to release surges of water in “waves” that can be a foot high.

Visible through the clear water on the creek bed are swirling patterns of black magnetite and occasional rocks containing white quartz, green chlorite minerals, and pink feldspar minerals, all semi-polished by the moving sand. Also on the creek bed are occasional concentrations of brightly colored, orange-and-yellow “chips” of bog iron. These consist mostly of goethite, a basic iron oxide that precipitates when iron dissolved in the water undergoes chemical and biochemical oxidation.

Along the east bank of Medano Creek, at the southern end of the dune-access parking area, are a crumbling stone wall and a rusted amalgamation vat. Largely buried in the shifting sand, they are all that remains of the Volcanic Mining Co.’s ill-fated gold mill.

Hiking the Dunes

Hiking the dunes in the Great Sand Dunes National Park is popular all year round. Some hikers look for fulgurites—small masses of fused silica that form in a millisecond from the impact of lightning bolts with temperatures above 3,270°F. Fulgurites (from the Latin fulgur, meaning “lightning”) are a variety of the mineraloid lechatelierite. Mineraloids are natural, noncrystalline, mineral-like materials with indefinite compositions.

At the Great Sand Dunes National Park, fulgurites occur as hollow tubes about an inch in length, with interiors of glassy, greenish, fused silica. Newly formed fulgurites have irregular, often spiny surfaces, but smooth quickly with weathering and abrasion. Since they are extremely fragile, fulgurites are often found as fragments. Fulgurites or their fragments appear as small, but noticeable, anomalies on the otherwise smooth surfaces of the upper sections of the dunes.

Always take precautions when hiking the dunes at the Great Sand Dunes National Park. Never hike barefoot in summer, as the sand temperature on sunny days can exceed 140°F. Also, get off the dunes immediately if you see lightning.

How Old Are the Great Sand Dunes?

Scientists are currently attempting to determine the age of the Great Sand Dunes using an experimental technique called optically stimulated luminescence dating (OSLD). OSLD is based on the ability of natural, low-level, geophysical radiation to energize electrons within quartz, which then become trapped in lattice imperfections. When quartz is on the surface, the energy of sunlight frees these trapped electrons faster than they can accumulate. But when quartz is buried in darkness inside, for example, a sand dune, the trapped electrons continue to accumulate at a known rate.

When quartz sand collected from the interior of sand dunes is artificially illuminated, its trapped electrons are freed and release excess energy as measurable luminescence, the intensity of which relates directly to the time that has elapsed since the quartz was last exposed to sunlight. Results indicate that quartz grains collected from interior sections of tall dunes were buried only 200 to 750 years ago, while those from deep beneath Medano Creek were buried 18,000 years ago.

An Outdoor Laboratory

The Great Sand Dunes National Park is both an outdoor laboratory for the study of sand-dune dynamics and the nation’s biggest recreational sandbox. During the summer, many visitors “ski” the dunes with specially designed sandboards and sand sleds. Others wade in the surge flow and build sand castles in Medano Creek, or pack folding chairs and coolers into the dune field for a relaxing day at the “beach.”

Removing any natural materials from Great Sand Dunes National Park and Preserve is prohibited, and that means fulgurites, naturally polished rocks, magnetite, and even the sand itself—although many visitors inadvertently take a lot of it home in their boots.

For further information, visit www.nps.gov/grsa.

This story about the Great Sand Dunes National Park previously appeared in Rock & Gem magazine. Click here to subscribe. Story and Photos by Steve Voynick