Hydrothermal vents are one of the most fascinating natural processes shaping our planet. Found along mid-ocean ridges and volcanic fault zones, these deep-sea geysers release superheated water rich in dissolved minerals. When the mineral-laden water meets the cold ocean, metals like iron, copper, and zinc solidify, building chimney-like structures known as black smokers. Since their discovery in 1979, hydrothermal vents have transformed our understanding of how mineral deposits form, both on the ocean floor and in ancient ore bodies now exposed on land.

Discovery of Hydrothermal Vents

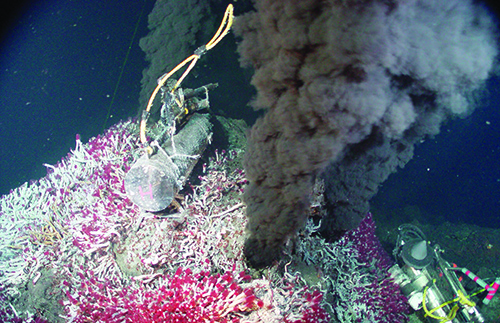

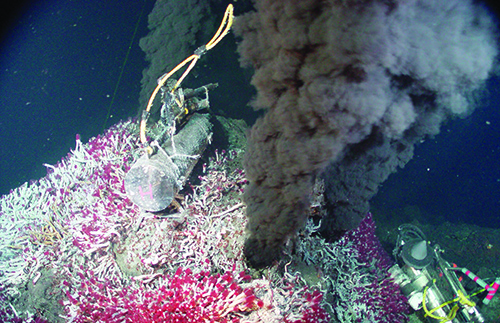

One of the most informative and significant modern discoveries about minerals happened in 1979 when scientists were doing deep ocean explorations along the East Pacific Rise, where crustal faulting and spreading, and volcanic activities were occurring. The research revealed super-hot, black waters gushing like geysers from the fault zones on the ocean floor. The water was super-hot because it was bursting from deep in an area of hot volcanic activity, under pressure that was exposed on the seafloor, that was slowly spreading apart along a major fault. These hot spring erupting areas were what scientists call volcanic vents, which are places where the super-heated waters within the crust are under such pressure that they have to burst forth.

But why was the water black? Later studies explained that the water was loaded with microscopic bits of various sulfide minerals of iron, copper, zinc, and, in some cases, other metals that had been dissolved out of the deep-lying crustal rock. When these gushing, hot, black fountains of water hit the cold ocean waters, they could no longer hold the dissolved minerals, which had solidified and formed chimney-like structures and covered the ocean floor with mainly iron, copper, and zinc sulfides. We see a similar phenomenon in Yellowstone Park, where hot water geysers out and forms chimney-like silica structures around the openings. The deep ocean black smoker “geysers” were actually mining minerals from the Earth’s interior.

How Black Smokers Form Minerals

The mechanism of these black smokers is relatively simple. Ocean waters are able to descend deep into the crust following cracks and faults that develop as the sea floor is pushed apart by rising molten volcanic material from the mantle below. Rising pressures push the lava up through the major faults and hydrothermal vents in the ocean floor. In some cases, it surfaces and forms islands. In other scenarios, it simply keeps shoving the Earth’s crust up, forming a ridge. The rising molten lava, under great pressure, raises the temperature of those descending waters to an exceptionally high temperature, well above the normal boiling point of water. It has been documented that superheated water under great pressure acts like a strong acid and dissolves almost any surrounding rock and minerals it encounters.

This accounts for the high metal content seen in black smokers. When the temperatures and pressure get high enough, the water has to explode or geyser out through the hydrothermal vent, which brings with it a mineral load. The 1979 discovery prompted the question of whether there were more hydrothermal vents and ancient black smokers. And, if so, were they responsible for some of today’s important mineral deposits?

Variations and Implications of Hydrothermal Vents

It also prompted the question: Are the black smokers found in 1979 an isolated event? Not at all. Black smokers have been found in many places, including the ocean floor, and not all of these hydrothermal vents are black. White smokers have been found as well. Their mineral content is obviously different and rich in calcium, silicon, and barium, which form a light-colored or white mineral compound.

Scientists realized that the metals of black smokers being “mined” by the hot water and brought to the ocean floor in hydrothermal vents might well be exposed millions of years from now by crustal movement, but mining them now is not feasible. But does the discovery of these mineral-rich smokers have any relation to modern-day mining? Yes, indeed! This is a story that is just being revealed, while scientists study today’s mineral deposits.

Ancient Hydrothermal Vents and Ore Deposits

Since its beginnings, the Earth’s crust has been experiencing cracking, shifting, faulting, continental collisions, subducting, mountain-building, volcanism, and more. In all those billions of years, there had to have been countless black smokers forming, building mineral deposits, and ending as the fault closes and appears somewhere else.

Also, what happened to the deposits of sulfide minerals that ancient black smokers laid down so long ago? Do we have evidence that any of today’s rich and productive mines and metal deposits were formed as black smokers in an ancient ocean? Yes, some ancient black smoker deposits are the focus of mining efforts. Since black smokers were discovered less than half a century ago, an understanding of them has only been applied to some of today’s metal deposits. We are still studying and trying to identify the metallic deposits of ancient black smokers, which is no easy task.

Jerome, Arizona: An Ancient Black Smoker Deposit

Fortunately, in Arizona, at least one deposit, the state’s richest deposit at Jerome, has proven to be an ancient black smoker deposit.

Jerome’s deposits are mined out, but a hundred years ago, the United Verde and United Verde Extension (UVX) mines on Cleopatra Hill, Jerome, Arizona, were the richest metallic deposits ever found in America. Mining at Jerome closed in 1953. We hear all about Bisbee, Morenci, Ajo, and other Arizona mines because the quantity of collector minerals from these deposits was great. Jerome was less generous with specimens, but for sheer dollar value of ore produced, Jerome tops them all.

Jerome’s mines produced over one billion dollars in copper, mainly from sulfides, including over 50 million pounds of zinc from sulfides, one and a third million troy ounces of gold, and more than 48 million troy ounces of silver. Yet, Arizona mineral collectors are hard-pressed to own a variety of mineral species from these richest mines. Jerome specimens were never common and are seldom seen on the market today.

Rare Minerals Formed by Mine Fires

However, Jerome did produce several of the most unusual and rarest mineral species ever found. They were not the natural product of Mother Nature but the result of a decades-long fire that started in 1894 underground at the United Verde mine. The fire seems to have started spontaneously when unstable sulfide ores were exposed to the air. Despite countless attempts to extinguish the fire, including flooding and shutting off access to air, the fire persisted. Open-pit mining finally breached the fire zone, and that action yielded nearly a dozen mineral species that had formed from available sulfide materials, water, and oxygen, plus the required heat from the fire.

Some of the fire-formed minerals proved to be new species when first studied. They are butlerite, guildite, ransonite, rogersite, and louderbachite. This latter species proved to be a known species. All the new minerals are sulfate minerals of iron, copper, or both.

(Mining History Association, www.mininghistoryassociation.org)

Jerome’s Early Mineral Significance

It so happens that the copper and gold deposit at Jerome also ranks as one of the earliest-recognized metal deposits in the Southwest. Local Yavapai Indians mined copper for decorative uses early on. When the Spaniards arrived in the area looking for Cibola, the city of gold, the local Indian miners showed them their little copper diggings, but the Spaniards were only interested in gold.

In 1882, underground mining began at Jerome on Cleopatra Hill. Its potential as a rich copper, gold, zinc, and silver deposit was soon recognized, mining increased, and Jerome grew exponentially. Saloons were plentiful, as was a red light area. In its boom days, Jerome was given the title of “Wickedest Town in the West.”

Jerome: Town History and Legacy

Buildings were constructed of wood, and, again and again, fires ravaged the town until the town fathers got smart and required all structures to be made of brick and stone. Unfortunately, that did not solve Jerome’s problems. The ground on the east-facing slopes of Cleopatra Hill overlooking the Verde Valley is a bit unstable, and through the years, the town, which was virtually abandoned after the mines shut down in 1953, has suffered the effects of gravity. It keeps encouraging the town’s buildings to slide downhill. Today, Jerome is a tourist town and is well worth a visit.

Modern Hydrothermal Vents and Jerome

Scientific studies have proven that the rich deposits at Jerome were formed by ancient black smokers about 1.74 million years ago during the Proterozoic Era by submarine volcanoes along part of an ancient inter-island arc structure. Technically, the deposits are described as “black smoker-type massive sulfide deposits.” It is interesting to point out that we still find such active black smoker activities in very similar geologic sub-oceanic areas in the deep waters of the western Pacific Ocean. If you plan on living a billion years, you might think about staking claims out there now.

Potential Ancient Black Smoker Mines

Are there other important mines that could be ancient black smokers? It is more than likely since black smokers have been part of the Earth’s crustal activities through the millennia.

I suspect the huge zinc deposits at Franklin and Sterling Hill, New Jersey, are ancient black smokers. They have obviously been through many of the same geological events found at Jerome, including vulcanism, faulting, and extreme metamorphism. In fact, the minerals found there often remind me of today’s black smoke findings. I have not read any science reports that identify these deposits of iron and zinc as such, but their development sure suggests they are. The deposits have been shown to have originated in volcanic areas in the ocean, which suggests possible black smoker origins. This is all very suggestive of a black smoker environment.

Another area I’m interested in is the silver mines of Mexico. If you plot the location of some of Mexico’s major silver mines, like Naica and Fresnillo, they seem to line up in a fairly straight trend, suggestive of a major ancient fault zone area.

Could they be ancient black smokers?

I was well aware that the deep-seated Sierra de Naica fault was just a couple of miles beneath us. The Naica silver deposit originated along that fault. Is this evidence of ancient black smokers? All things to consider.

The Ongoing Fascination with Minerals

These examples highlight why the study of hydrothermal vents and black smokers is so compelling. Understanding how minerals form, both in the deep sea and in ancient deposits on land, continues to reveal unanswered questions about Earth’s geology — a curiosity that keeps mineral collectors and scientists alike engaged.

This article about hydrothermal vents and black smokers was written for Rock & Gem magazine. To subscribe, click here. Story by Bob Jones.