Story and Photos by Steve Voynick

One of the world’s foremost collections of leaf and wire gold is displayed at the Denver Museum of Nature & Science. It consists of 100 of the finest pieces from the John F. Campion crystallized gold collection, including the spectacular 102-troy-ounce specimen known as “Tom’s Baby.” All these specimens have one thing in common: They were mined in Breckenridge, Colorado.

Located 70 highway miles west of Denver, at an elevation of 9,600 feet, Breckenridge today is a bustling resort town filled with glitzy bars, fine restaurants, and high-end boutiques. Winter skiing and summer recreation attract thousands of visitors each year.

But in its previous life, Breckenridge was one of Colorado’s greatest gold-mining towns. It produced 1 million troy ounces of gold, pioneered the regional use of floating, bucket-line dredges, and played a major role in establishing both an appreciation for the rarity and aesthetics of crystallized gold and a premium valuation of fine gold specimens.

Although Breckenridge’s last mine closed decades ago, its rich mining history is still celebrated through a downtown museum, three outdoor mining museums, several gold-panning sites, and an underground-mine tour.

Breckenridge’s Golden Beginning

Breckenridge was founded in 1859, late in the Pikes Peak Gold Rush, by prospectors who panned their way west across the Continental Divide into the Blue River drainage and struck gold in a small creek now known as Gold Run.

102-troy-ounce section of “Tom’s Baby” is on display at the

Denver Museum of Nature & Science.

That name was fitting, given that two brothers, using only gold pans and a wooden sluice, washed out 1,000 troy ounces of gold in just six weeks. Gold Run was the richest of the initial strikes in the Blue River Diggings, which would soon become known as Breckenridge.

Other prospectors found gold in the nearby gravels of Georgia, American, French and Humbug gulches and the Blue and Swan rivers. Two thousand prospectors soon surged into the Breckenridge Mining District; in just the next three years, they would recover 50,000 troy ounces of gold worth nearly $1 million.

Once the shallow discovery gravels had played out around 1870, prospectors began searching for lode sources of the placer gold. Although they found little lode gold, they discovered rich deposits of sulfide ores of silver, lead and zinc. After silver became the primary metal of economic interest, the district boasted 20 underground mines, several mills, and a central smelter.

Spotting Silver, Seeking Gold

While silver mining paid the bills in Breckenridge during the 1870s and ’80s, prospectors continued to search for lode-gold deposits. Many focused on French Gulch, just north of Breckenridge, where placer gold occurred not as rounded grains, but as fragments of sharp-edged wires and leaves that had obviously originated in a nearby lode deposit.

One of the French Gulch prospectors was Harry Farncomb, who arrived in Breckenridge in 1860, but hadn’t yet struck it rich. In 1879, still looking for a big find, Farncomb worked his way up French Gulch searching adjacent hillsides for gold-quartz outcrops. Near the head of the gulch, he stopped at a low, rounded hill. Judging from its surface of loose, “rotten” shale with no visible quartz outcrops, it was an unlikely place to find lode gold.

Nevertheless, he dug a few holes and, much to his surprise, sunk his pick into a rich, eluvial gold deposit, the remains of a gold-quartz vein that had weathered away in place and was buried beneath several feet of decomposed, gray shale. Noting the similarity of the eluvial gold leaves and twisted wires to those in the lower placers, Farncomb knew that he had found the source of the French Gulch placer gold.

Farncomb also knew that announcing his find would trigger a chaotic, local gold rush. So he kept his discovery to himself and quietly staked a claim that he named the Wire Patch Placer. During the following months, he conducted a low-key, pick-and-shovel mining operation, while casually buying up adjacent ground an acre at a time.

A year later, Farncomb walked into a Denver bank and deposited 300 troy ounces (25 pounds) of gold in—according to the bank’s description—“most unusual forms”. When word of this deposit reached Breckenridge miners, they rushed, as Farncomb had predicted, to French Gulch, only to learn that he already owned the richest ground.

Fascination With Farncomb Hill

After mining the eluvial gold, Farncomb drove a short drift into the hillside to find

of the largest mass of gold ever mined in Colorado.

a series of erratic, but extremely rich, gold veins knifing through the in situ shale. He named his little underground operation the Wire Patch mine, and in just two years he recovered 7,000 troy ounces (580 pounds) of wire gold then worth nearly $140,000! In 1886, Farncomb sold his holdings on what had become known as Farncomb Hill and retired as one of Colorado’s wealthiest men.

Farncomb Hill had six major gold veins—the Bondholder, Boss, Fountain, Gold Flake, Key West, and Ontario—that were emplaced in both the underlying porphyry country rock and the overlying shale. The shale, a soft, sedimentary rock that weathers quickly, was the reason that Farncomb Hill had no visible quartz exposures: it had decomposed completely into a clay-like soil that buried the fragmented gold-quartz veins.

Underground mining at Farncomb Hill involved a great deal of luck. The veins either “pinched out” to nothing or “blossomed” into bonanza pockets filled with crystallized gold in a rust-colored matrix of limonite (a mix of iron oxides and hydroxides). The gold was 90% pure; a small copper content sometimes imparted rich, warm colors that enhanced the visual appeal of its crystallized forms.

The crystallized gold at Farncomb Hill occurred as wires, leaves, and arborescent masses. The wires were as long as 2 inches and up to ¼ inch thick. Intricate, tangled masses of these wires were called “bird’s nests”. The delicate, flattened, arborescent growths were as long as 3 inches and had a spongy, flexible feel.

Most common was leaf gold, which formed parallel intergrowths of thin, flattened octahedrons as long as 6 inches.

Influencing Public Interest in Collecting

Farncomb Hill’s crystallized gold had a major impact on the valuation of gold specimens and on public interest in mineral collecting in general. Previously, very little gold mined anywhere had been preserved for mineralogical or aesthetic reasons. Gold had traditionally been assessed only by purity and weight to determine its bottom-line, bullion value. Because premium specimen values did not yet exist, all native gold, regardless of form, was assayed, weighed, and melted down into bullion.

The appreciation and value of specimen-grade gold began changing in 1886, thanks initially to Colonel Albert J. Ware, Farncomb Hill’s first consolidated mine owner. Ware leased sections of his mines to independent miners in return for cash fees and a 25% royalty on all recovered gold. This royalty, payable as mined gold, enabled Ware to build the first collection of Farncomb Hill crystallized gold.

To attract investment capital for his mines, Ware displayed his growing collection at Eastern fairs and expositions. The intricate shapes, rich colors, and bright luster of his specimens ignited public interest in fine gold specimens. Ware also sold some pieces for prices based not on purity and weight, but on aesthetics and rarity. By asking for and receiving prices for his specimens that were above their bullion value, he established a premium collector value for fine gold specimens, a concept that soon extended to the valuation of specimens of many other kinds of minerals.

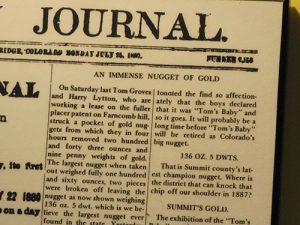

Farncomb Hill’s most celebrated piece of crystallized gold was recovered on July 23, 1887, when lease miners Tom Groves and Harry Lytton, working on the Gold Flake Vein, blasted into a pocket filled with 243 troy ounces of gold. The largest piece originally weighed 160 troy ounces (13.3 pounds), but after two sections separated, the largest remaining piece weighed 136 troy ounces. Cradling that piece in his arms, Groves paraded through the streets of Breckenridge.

Onlookers named the gold mass “Tom’s Baby.” The Breckenridge Journal reported the event in detail under the headline “An Immense Nugget of Gold”.

High-Grading Rampant Run

“High-grading”, the miners’ practice of stealing gold almost as quickly as they mined it, was rampant at Breckenridge. Although the courts agreed that high-grading was a criminal act, miners justified it as earned, supplementary compensation for their long hours in the dangerous, dark confines of the underground.

By the late 1880s, Breckenridge miners, looking to cash in on the newly established, premium collector value of crystallized-gold specimens, had become master high-graders. Wealthy Denver residents building their own collections of crystallized gold often visited Breckenridge to buy high-graded specimens directly from them. A Colorado School of Mines geologist of the time observed that more Farncomb Hill gold was “stolen by miners and sold as specimens than was ever shipped by the owners”.

The greatest gold collector of all was Denver-based mine owner John F. Campion. After acquiring several Farncomb Hill properties in 1894, Campion began building an unparalleled collection. He offered to buy all crystallized-gold specimens—even from his own high-grading miners—at prices well above those being paid on the Breckenridge streets and with no questions asked. While colleagues ridiculed his policy of “buying gold that already belonged to him”,

Campion amassed one of the world’s finest collections of crystallized gold.

Campion helped to found the Denver Museum of Natural History (now the Denver Museum of Nature & Science). One of his founding gifts was his entire 600-piece collection of Farncomb Hill gold, which included “Tom’s Baby”. A 102-troy-ounce section of the specimen is on public display there today.

By the late 1890s, when Farncomb Hill was largely mined out, Breckenridge miners redirected their attention back to the district’s placer deposits. These were geologically classified as high-level or low-level. The high-level, or terrace, placers occurred in hillsides above the water levels of the creeks and rivers. The more geologically recent low-level, or deep, placers were found on or near bedrock in the river gravels.

Emergence of Churn Drilling

Back in the 1860s, Breckenridge miners had worked these shallow, low-level placers by sluicing and ground sluicing. But by 1890, with the easy-to-reach, shallow gravels long depleted, they began hydraulic mining of the high-level terraces. Fed by water piped down from high lakes, nozzles emitted high-pressure streams that quickly eroded away entire hillsides. Miners then recovered the gold by channeling the hillside-gravel slurry through massive steel sluices.

Churn drilling, the forerunner of modern core drilling, revealed that far more gold was present deep in the low-level river gravels at or near bedrock. But buried at depths of 30 to 90 feet, there was no way to reach it—until a Breckenridge mining engineer named Ben Stanley Revett took on the challenge.

Revett, one of Campion’s mine supervisors, saw a solution in the floating bucket-line dredges that had recently been developed in New Zealand. Resting on large, floating hulls, these dredges had long, forward, boomlike gantries supporting continuously rotating lines of steel buckets that could be lowered below the water. A rear “stacker” conveyor disposed of tailings. The interiors of the dredges were filled with steel screens, grates and sluices that separated the gold from sand, gravel and boulders.

These dredges created the ponds they floated on by excavating gravels in front and dumping tailings behind. Dredges with 250-foot-long hulls could process about 2,000 cubic yards of deep gravels per day.

Although Revett’s first dredge, which began operating in 1898, was steam-powered, prone to breaking down, and notoriously inefficient, it could nevertheless recover gold from previously unreachable gravels. Within a few years, several vastly improved, electrically powered dredges would also be profitably mining the deep gravels of French Gulch and the Swan and Blue rivers.

Dynamic Dredging

By 1916, a fleet of nine dredges had become known as the “Breckenridge navy.”

Amid the round-the-clock din of humming electric motors, clanking bucket lines, and clattering tailings, these dredges recovered about 20,000 troy ounces of gold per year and established Breckenridge as Colorado’s most productive placer-gold district.

The dredges recovered many 1-troy-ounce nuggets, along with some nuggets of 6 troy ounces or more, few of which, unfortunately, have been preserved. The dredges also recovered occasional small nuggets of native silver and bismuth.

In 1942, wartime gold-mining restrictions shut down the Breckenridge navy, and the dredges never resumed operations. By then, however, Breckenridge had produced 1 million troy ounces (58 tons) of gold, three-quarters of it from placer deposits, and most of that by dredging.

During World War II, many Breckenridge underground, multimetal mines, including the Washington, Wellington, and Country Boy, produced lead and zinc for the war effort, along with a good deal of silver. By the time these mines closed after the war, the district’s total production had topped 20 million troy ounces of silver and thousands of tons of lead and zinc. Even so, Breckenridge was never known for its metal-sulfide specimens. While its sulfide ores were often rich, they occurred only in massive forms that were of little interest to collectors.

By 1960, Breckenridge had devolved into a down-and-out, busted mining town with dirt streets, a decimated population, and little hope for the future. The biggest problem was the environmental mess left behind by a century of unregulated mining—10 miles of river channels buried beneath undulating heaps of dredge tailings, barren of minerals and life.

Celebrated for Its History

But after skiing caught on in the 1960s, land values took off and vast expanses of dredge tailing were reclaimed, notably along the rechanneled Blue River, where attractive parks, gardens, river walks, and bike trails now entice visitors. And thanks to extensive preservation and restoration of 350 structures dating back to the 19th century, Breckenridge has become Colorado’s largest historical district.

Despite its many transitions, Breckenridge has not forgotten its mining history. An excellent museum in its downtown Welcome Center explains the various phases of Breckenridge mining. Immediately south of town, the circa-1880s Washington mine is now the Washington Gold and Silver Mine Tour that welcomes visitors with a short, guided underground tour and displays of hardrock mining equipment.

Just north of town, the Lomax Placer Mine museum and the Iowa Hill Trail recall the hydraulic-mining era. The Lomax mine displays sluices and hydraulic-mining equipment, offers gold panning, and presents a video about hydraulic mining. The Iowa Hill Trail is a mile-long, self-guided tour of an 1890s hydraulic-mining operation.

Especially popular is the Country Boy Mine attraction in historic French Gulch. The Country Boy opened in 1887 and, over 60 years of mining, recovered 8,000 troy ounces of gold, along with huge tonnages of silver, lead and zinc. A guided tour takes visitors through 1,000 feet of well-lit, underground workings. The Country Boy also has underground and surface displays of mining equipment, a video presentation about early mining, and a gold-panning site.

Directly across French Gulch from the Country Boy are the remains of the Wellington mine, the district’s largest mine, with 14 levels and 18 miles of underground workings. A major multimetal producer, the Wellington was the last Breckenridge mine to close.

Remains of Mining Production

Science with the

gift of his entire

600-piece collection

of Farncomb Hill gold,

including this 6-inch specimen of leaf gold.

Dredge tailings still cover much of French Gulch, where the remains of an old floating dredge are still visible. Upper French Gulch is also the site of Farncomb Hill, an area that is now posted, private property.

Breckenridge still has one floating “dredge”, but it does not mine gold. Located in downtown Breckenridge, The Dredge, billed as “the world’s highest floating bar and restaurant”, floats on an impounded section of the Blue River, directly over the sunken hull of an old bucket-line dredge. Its size and exterior appearance replicate the big dredges of the old Breckenridge navy, while its comfortable interior is decorated with mining artifacts. The Dredge is a good place to cap off a day’s visit to the historical mining attractions at one of Colorado’s greatest historic gold camps.

Breckenridge is located about nine miles south of Silverthorne. From Interstate 70, take Exit 205 and go south on state Route 9.

For further information about Breckenridge’s history and mining attractions, visit the websites of the Breckenridge Heritage Alliance (www.breckheritage.com) and the Country Boy Mine (www.countryboymine.com).

Author: Steve Voynick

A science writer, mineral collector, and former hard rock miner, he is also the author of many references including, “Colorado Rock Hounding” and “New Mexico Rockhounding.”

A science writer, mineral collector, and former hard rock miner, he is also the author of many references including, “Colorado Rock Hounding” and “New Mexico Rockhounding.”