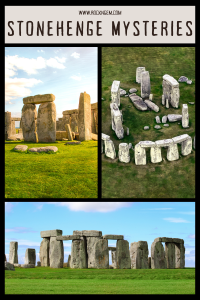

Stonehenge leaves many visitors convinced that the place is haunted. Some say that’s because Stonehenge is set amid a vast Neolithic burial ground. But others claim that the great stones making up this ancient monument exude an almost palpable sense of timelessness, magic and mystery.

Archaeologists describe Stonehenge as a megalithic structure—a monument built of one or more exceptionally large stones. Of the world’s thousands of Neolithic megaliths, none can approach Stonehenge in name recognition, scientific attention, spiritual significance and historical and metaphysical interest.

Located 85 miles west of London, England, on the misty Salisbury Plain, Stonehenge is variously described as a ghostly ruin, religious temple, astronomical observatory, healing center and burial ground. And at different times, it has likely served all these purposes. Stonehenge remains a great mystery: We still do not know who built it. Or why. Or how.

The Megalith and the Making of Stonehenge

Salisbury Plain, occupied by humans for over 10,000 years, was a major Neolithic cremation-burial site long before Stonehenge was built. Archaeologists believe the monument was constructed in three general phases beginning about 3100 B.C. and ending in 1600 B.C.

The first phase was the emplacement of a circular, 350-foot-diameter trench and earthen bank. Some 500 years later, work began within the circular enclosure on a concentric stone circle with three sections. The outermost, 110-foot-diameter circle consisted of shaped, vertical sarsen stones. The sarsen stones are each about 13 feet high, 7 feet wide, and weigh 25 to 30 tons. A number of these massive sarsen stones remain upright and are topped by interconnecting, horizontal stone beams called lintels that give Stonehenge its distinctive character.

The middle of the stone circle consists of smaller volcanic “bluestones.” At the center of this circle are several sarsen trilithons, each with two vertical sarsens joined by a lintel—the familiar shape represented by the mathematical symbol “π” that has come to symbolize Stonehenge.

The ruins seen today are the product of a 700-year-long series of rearrangements and reworkings. Stonehenge was probably never completed. If it were, models of its hypothetical completion indicate that many stones, both large and small, were later removed for unknown reasons.

Unraveling the History Behind the Stonehenge Mysteries

At various points in history, the creation of Stonehenge has been attributed to the ancient Phoenicians, Celts, Romans and Vikings. In truth, it predates all these civilizations and goes back to the Late Neolithic and early Bronze Ages. Its creation is only vaguely attributed to “Neolithic-age Britons.”

Etymologists say the name “Stonehenge” stems from the Saxon word stan-hengen meaning “stone-hanging” or “gallows,” since some of its stone structures look like old-style gallows where two posts are supported by a crosspiece. Archaeologists have since borrowed the “henge” as a formal term for circular, banked earthwork enclosures with internal ditches of Neolithic age.

The first surviving written record of Stonehenge appears in the 1136 C.E. History of the Kings of Briton by cleric Geoffrey of Monmouth, who created much of the King Arthur legend. Geoffrey wrote that Merlin the Magician built Stonehenge by directing giants to move the massive stones from Ireland, an idea that persisted well into the 1500s.

The creation of Stonehenge was next attributed to learned Celtic priests called druids, a belief that remained popular for the next 300 years. But by the late 1800s, archaeologists had proven that Stonehenge had been built long before the Celts ever arrived in Britain.

In 1882, the British government declared Stonehenge a “scheduled monument,” the English term for a protected site of national importance. By then, when Stonehenge was already attracting archaeologists, treasure hunters, historians, tourists and the curious, the government had begun the first of a limited series of “restorations” to straighten leaning stones and set them in concrete.

After a landowner donated Stonehenge to the government in 1918, interest arose to “fully restore” the monument, but the idea was soon dropped for a good reason—no one knew what Stonehenge’s original builders had envisioned.

Solar Alignment and the Astronomical Mysteries

The Neolithic Britons who built Stonehenge were primarily farmers and well aware of seasonal and solar cycles. By the 1700s, surveyors realized that Stonehenge was carefully aligned with the movements of the sun and that certain stones precisely framed two major, annual solar events: the summer solstice sunrise and the winter solstice sunset. The word “solstice” is appropriately derived from the Latin solsticium, literally “point where the sun stands still.”

Neolithic people likely gathered at Stonehenge on the solstices to celebrate the changes in the sun’s movement. Archaeological excavation has revealed that the monument is generally “clean,” with no indication of ancient feasting, encampments, fires and other signs of long-term use, a possible indication that Stonehenge was a sacred place reserved only for the elite to witness “the sun standing still.”

By 1600 B.C., Stonehenge had been abandoned for unknown reasons. The site apparently was not used again to celebrate the solstices until the 1860s, after public lectures had stirred interest in the monument’s solar alignment. Visitor numbers increased steadily, and by 1900, neo-druid, neo-pagan, and Wiccan groups had adopted Stonehenge as their sacred ceremonial site.

The Stones Themselves: Clues to the Mysteries

The circular monument at Stonehenge is made up largely of two types of stone: sarsen and Pembroke bluestone. The massive standing stones (the megaliths) consist of sarsen, a sandstone that outcrops across much of southern England. Physically similar to quartzite, sarsen is a hard, resistant silcrete material in which sands and gravels are cemented together by silica.

Oddly, neither the massive sarsen stones nor the smaller bluestones are found in the immediate area of Stonehenge. In 2014, geologists noted that the monument’s sarsen stones shared a similar chemistry and thus likely had a common source. After comparing the chemistries of stones from sarsen outcrops across England, they concluded that the Stonehenge sarsen had come from an outcrop near Marlborough, 15 miles from Stonehenge.

More puzzling was the origin of the smaller, three-to-four-ton bluestones. Named for their gray-blue coloration when wet, bluestones consist of rhyolite or dolerite, igneous rocks chemically similar to basalt.

Geologists had long suspected that Stonehenge’s bluestones came from the Preseli Hills in South West Wales. But the great distance from Stonehenge—140 miles—made it unlikely that the Preseli Hills were the source of the monument’s bluestones. Additional scientific speculation suggested that the Irish Sea Glacier, which scoured southern England 400,000 years ago, had transported the bluestones nearer to Stonehenge. That theory was refuted in 2011 when geologists discovered a Neolithic bluestone quarry in the Preseli Hills where the stones matched those of Stonehenge in chemistry and uranium-lead dating. Recesses in the quarry walls even matched the shape of several Stonehenge bluestones.

While science has now determined the origin of the Stonehenge sarsen and bluestones, it has not answered how Neolithic cultures transported these massive stones to distant Stonehenge.

The Wider Landscape of Stonehenge Mysteries: Avebury and BeyondIn 1986, the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) listed Stonehenge as a World Heritage Site, a landmark or area of unusual cultural, historical, natural or scientific significance. Today, the 1,099 World Heritage Sites worldwide are recognized as having outstanding universal value and deserving special attention under the Convention Concerning the Protection of World Cultural and Natural Heritage. Many antiquarians and archaeologists consider Stonehenge not as an isolated ruin, but as part of a large complex of Neolithic burial sites and monuments. As a World Heritage Site, Stonehenge is formally listed as “Stonehenge, Avebury and Associated Sites,” which includes two large areas 17 miles apart with some 700 individual archaeological features. While Stonehenge is known worldwide, Avebury is much less familiar. And although Stonehenge is the world’s most architecturally sophisticated stone circle, Avebury is far larger, albeit less visually striking. The Avebury henge, the outer encirclement of ditch and bank, measures 1,140 feet in diameter—three times that of the henge at Stonehenge. The two separate stone circles within the Avebury Henge are roughly the same diameter as the Stonehenge circle, but have only a few remaining upright stones. Avebury is also the site of Silbury Hill, which, with a height of 129 feet and covering five acres, is the world’s largest Neolithic mound. Like Stonehenge, Avebury is a major archaeological site and tourist attraction, as well as a place of religious significance. Also, like Stonehenge, who built it and why remains a mystery. |

Stonehenge Today: Preserving the Monument and Its Mysteries

The Stonehenge that we see today is incomplete. Many sarsens and bluestones were apparently removed or broken up, likely during England’s Roman and medieval periods. Much later, treasure hunting and archaeological excavation, along with limited restoration, other human activities, and erosion, have severely disturbed the ground.

Stonehenge’s popularity as a “New Age” site soared between 1972 and 1984 when the Stonehenge Free Festival drew tens of thousands of summer solstice visitors each year. When crowd control and site damage got out of hand, journalists called the festival a “Neolithic Woodstock.” When a court ruling closed the site in 1985, violence erupted between police and festivalgoers. Stonehenge was closed to all religious activities during the solstices and equinoxes for the next 15 years. This exclusion order was overthrown by a higher court in 2000, which ruled that any religion—including neo-druidism, neo-paganism, and other “old, Earth-based” religions—had a right to worship in its “own church.”

Today, Stonehenge is owned by the British Crown and managed by English Heritage, a charitable trust that oversees more than 400 historic buildings, monuments and sites throughout England. Stonehenge attracts more than one million visitors each year. The Stonehenge Visitor Centre showcases old photographs, living history exhibits, multi-media programs and a collection of Neolithic artifacts recovered at Stonehenge. Most visitors are only allowed to walk around the monument. Special permits are required to enter the monument during the summer-winter solstices and spring-fall equinoxes. Especially popular are the hour-long, guided “Stone Circle Experience” tours that bring limited numbers of visitors into the stone circle throughout the year.

Stonehenge seems to have always been a work in progress, and it is impossible to pinpoint any predominant use of this great monument. Its purpose likely changed over its long history as different societies came and went. And with our questions unlikely to ever be answered, Stonehenge seems destined to remain England’s magnificent megalith of mystery.

This story previously appeared in Rock & Gem magazine. Click here to subscribe. Story by Steve Voynick.