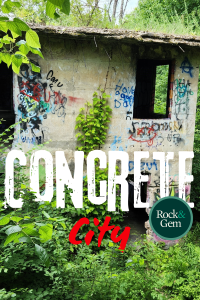

Concrete City was not a city, but a planned community of twenty concrete duplexes built in 1911 for select coal mining employees of the Truesdale Colliery in Nanticoke, Pennsylvania. In the early 1900s, concrete was an ultra-modern building material, and the Colliery owners wanted to provide their managers with quality housing. Unfortunately, despite their efforts, living in concrete housing was awful, as it was always damp and cold, and the lack of indoor plumbing made it worse. The community was abandoned by 1924. Today, Concrete City is a ghost town. It is not a typical ghost town in a quiet forest with a few remaining foundations, but a spooky ghost town with long-abandoned buildings and dark rooms that you should avoid when it gets dark.

Anthracite Coal in Pennsylvania

To understand how the Concrete City came to be, it is important to understand anthracite coal and its importance. Anthracite coal is “hard coal” as opposed to bituminous coal, which is “soft coal.” It is easy to identify anthracite in the field as it is hard, black and has a submetallic luster. It often has iridescent surfaces when broken.

While there are different grades of anthracite, in general, it is a high carbon, low sulfur coal that can be crushed and graded as needed for its intended uses for fuel, steel production and water treatment. Anthracite burns with intense heat and produces a blue flame, making it an excellent source for heating and metal production, but its relative scarcity makes it more expensive than bituminous coal.

Northeast Pennsylvania has the largest known deposits of anthracite in the world. China, Poland, Russia, South Africa and India also have anthracite. Production of anthracite in northeast Pennsylvania has been greatly reduced as it has become too expensive to use for fuel for electrical power generation.

The main demand for anthracite now is from the steel sector. High-grade anthracite is used as a cost-effective alternative to coke in blast furnaces. In electric arc furnaces, anthracite is used as injection coal, known as foam coal, to produce foam slag. Controlled foaming of slag improves the coupling behavior of the arc and extends the service life of the furnace lining.

While the power sector demand has been reduced, Pennsylvania anthracite has seen a significant increase in price since 2022 because of the Russia-Ukraine war. Russian anthracite could no longer be imported, so the demand for high-quality Pennsylvania anthracite increased quickly.

Truesdale Colliery and Its Breaker

Today, it is hard to imagine the Wilkes-Barre region, which includes Nanticoke, around the beginning of the 20th century. Gigantic wooden structures known as “breakers,” which were built to process the extracted coal and get it ready for market, were prominent features near the coal mines and dominated the landscape. These structures were huge, and grading coal and removing waste rock was hard and dangerous. The owners had little regard for safety, and you could just as easily be killed or maimed in the breaker as well as underground in the coal mine.

The terms “colliery” and “breaker” are often used interchangeably, but they are not the same. A colliery is where the coal is extracted and often refers to the mine or mines and associated property. The breaker is the coal preparation plant. All collieries had breakers, but all breakers were associated with one or more collieries.

The Truesdale breaker was part of the Truesdale Colliery and was in the Hanover section of Nanticoke. It was the largest breaker in the region. The Truesdale Breaker was built in 1905 by the coal department of the Delaware, Lackawanna and Western Railroad Company (often called the DL&W) at Nanticoke, Pennsylvania. It was named after W.M. Truesdale, who was the DL&W president. The operation employed over 1,700 men, who were mostly Lithuanian, Polish and Russian immigrants. Between 1914 and 1916, the Truesdale colliery outproduced every other colliery in Luzerne County, producing more than a million tons of anthracite coal each year.

In 1916, the colliery set a world record, producing 1,689,910 tons of anthracite coal, which amounted to 20 percent of all the hard coal produced in the region. In 1920, due to antitrust laws, DL&W was forced to divest its coal properties. By 1921, the Glen Alden Coal Company took control of Truesdale and all other DL&W coal properties.

The Truesdale Breaker was destroyed by fire in 1953. Being a wooden structure, its destruction by fire was a fate common to many breakers in the region. Practically all the old breakers are long gone.

History of Concrete City

Under Truesdale’s leadership, DL&W constructed the Tunkhannock Viaduct railroad bridge in Nicholson, Pennsylvania. At the time of its construction from 1912 to 1915, it was the largest reinforced concrete railroad bridge ever built, and it is still in use. Truesdale was a big supporter of concrete, and this may have led to the fateful decision to build the Concrete City.

Concrete City Housing Challenges

The paint peeled, the plaster fell off and the insides of the houses were cold and damp. Concrete was a poor choice for the brutal Pennsylvania winters of the early 1900s. The houses could not stay warm, despite having coal furnaces and stoves. Shirts in closets would freeze solid and had to be ironed just to put them on. The community was also marred by tragedy when a boy drowned in the adult swimming pool. Both the wading and adult pools were soon filled in.

The Concrete City had concrete outhouses, as indoor toilets were too expensive, even for managers. The community was also served by a well in the center of the courtyard, and the lack of proper drainage and septic systems was likely bad for water quality. The local government soon required that the houses must have a proper sewage system, and this was too expensive for the Glen Alden Coal Company. The houses were abandoned by 1924.

The company tried to demolish the houses using explosives. A house was loaded with 100 sticks of dynamite, but the massive explosion only blew out the windows and doors, and the concrete remained intact. It was too expensive to bring down the houses, so the Glen Alden Coal Company just walked away. It became another problem to ignore, just like the industry ignored its other legacy issues.

Concrete City: The Ghost Town

It was called “The Garden City of the Anthracite Region.” Construction started in 1911 of twenty identical two-story poured concrete duplexes, arranged in a rectangle around a central courtyard. This was state-of-the-art housing for select company employees. The courtyard included a wading pool, adult swimming pool, tennis courts and a baseball field. Pictures after the families moved in show that the community was well-landscaped and maintained.

While concrete made strong structures, it was porous and a poor insulator. It was not good for residential construction. The buildings were painted and plastered.

Concrete City and Anthracite Mining

In 1961, the Glen Alden Coal Company caused a huge fish kill by dewatering their south Wilkes-Barre coal mines and pumping untreated mine water directly into Solomon’s Creek, which emptied into the Susquehanna River.

They did not just kill fish, but also affected the drinking water companies and pharmaceutical companies that used the water from the river. Luzerne County municipalities began to question why they were spending millions to install sewage treatment systems, such as the one that would have served the Concrete City, only to have the river polluted by coal companies, who were exempt under Pennsylvania’s Clean Streams Law. Glen Alden officials denied any wrongdoing and said the State Department of Health was hassling the company by insisting it treat mine water discharge before releasing it into the river.

A few years later, the laws were changed to no longer exempt coal companies. The companies spent their last years in court fighting the new regulations, but it was the last gasp of the once mighty anthracite industry.

Adobe Stock / By Tom

Visiting Concrete City Today

I have been to Concrete City several times. It is easily accessed from Hanover Street, and parking is available on both sides of the road. During my last visit, the parking area had about five cars, so I expected to see many people.

The road to the city has a gate and is unpaved, but I did not see any No Trespassing signs or other indications restricting access. A walking path is around the gate. The road has lots of shale, which is carboniferous and sometimes has plant fossils. Fist-sized pieces of shiny anthracite can be found along the road.

I soon could see the concrete houses through the trees. They are covered with graffiti. All the doors and windows are gone. I walked into one of the houses. Broken glass and trash covered the floors, and the walls had multiple layers of graffiti. I walked to the stairs that led to the basement, and here it became dark enough to need my phone flashlight. Fortunately, no one was hiding in the basement.

It was a bright sunny day, and I could hear other visitors. I soon smelled spray paint. A group near me was painting one of the walls and the odor was strong. There are no blank walls at the Concrete City. Some graffiti shows real talent and is colorful, but most markings are obscene words and imagery. New graffiti covered most of the images I saw during earlier visits, so even the best artwork is fleeting. Modern spray paint sticks to the concrete walls better than the original paint used for the houses.

Safety and Hazards at Concrete City

All the visitors I met were friendly. Most were groups of teenagers or twenty-somethings out to enjoy the day, albeit with cans of volatile spray paint. If the Concrete City were a business, it would require an air quality permit. A strong smell of marijuana, which I now take for granted in cities and parks, also dominated the breathing zone at times.

During discussions with some of the visitors, we agreed this was an eerie place and that it takes on another character when the sun goes down. We also noted that it could be quite dangerous, as some of the concrete walls and roof overhangs have collapsed, and the second-story floors have huge holes that you could fall through if you were not careful. In addition to the teenagers and painters, there were also many ATV and dirt bike riders near some of the buildings. I did not talk to them, but they seemed to be enjoying their day here as well.

Concrete City Directions

The City of Nanticoke reportedly owns the land beneath the Concrete City. As of June 2024, the area is not posted against trespassing. There are no problems with access. To get to the site, park at the coordinates below, and walk across Hanover Street to the dirt road that goes north. The site is plainly visible on both Google Maps and Google Earth. Concrete City is west of the dirt road, and the houses can be seen through the trees approximately 800 feet north of Hanover Street.

The following are GPS coordinates:

- Parking: 41°11’12.5”N 75°58’26.3”W

- Concrete City: 41°11’21.3”N 75°58’33.8”W

I have never been to the Concrete City at night. If you believe in ghosts, you should consider coming here during a new moon in late fall near Halloween, when the darkness is not just ordinary darkness but advanced darkness. Shine a flashlight into the windows, and you may get more than you bargained for, especially if you imagine you encounter a real ghost and not just other ghost seekers.

This story about Concrete City previously appeared in Rock & Gem magazine. Click here to subscribe. Story by Robert Beard.