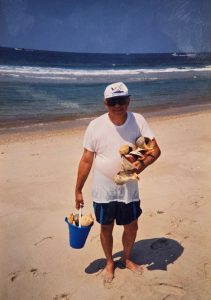

Outer Banks shelling draws collectors to a pristine 200-mile stretch of barrier islands that hugs the mainland from Back Bay, Virginia, to Cape Lookout in North Carolina, with another fifty-five miles of the Bogue Banks shoreline to Atlantic Beach. These unspoiled beaches are among the best spots for shelling and beachcombing. Collectors can find whelks, scallops, scotch bonnets (the North Carolina State shell), conches, periwinkles, sundials, olive shells, sand dollars, shark teeth and sea glass. Also, small ocean-tumbled pieces of the violet-and-white quahog shell known as wampum, which is great for jewelry.

The Outer Banks is an area steeped in history with a shoreline dotted with famous lighthouses, visitor centers and museums, national seashores and wildlife refuges. It’s also a haven for all summer sports.

Lighthouses of the Outer Banks: Beacons on the Barrier Islands

The North Carolina Outer Banks are narrow islands with ocean beaches, sand dunes and salt marshes, tranquil most of the time, but at times strong winds, treacherous hurricanes, and blowing sand over the roads change the landscape. They are also the resting place of many shipwrecks and the fuel for local lore, ghosts and legends.

On the first long barrier island, just north of Nags Head, is the town of Kitty Hawk, famous for its aviation history and museum. The Wright Brothers National Memorial site commemorates the birthplace of man’s first flight on December 17, 1903.

Five lighthouses dot the Outer Banks seashores, starting with the red brick Currituck Lighthouse in the north, the Bodie Island Lighthouse (part of the Cape Hatteras National Seashore Park) just south of Nags Head, and the Cape Hatteras, Ocracoke and Cape Lookout Lighthouses. Each is distinct in color or body stripes, and flashes a distinctive timed signal at night to help seamen navigate the treacherous coast. Each lighthouse has a visitor center. A bridge connects the northern barrier island with Hatteras Island crossing over the Oregon Inlet, which is headquarters for charter fishing boats and the Atlantic blue marlin fish.

A ferry connects Hatteras Island with Ocracoke Island. The Ocracoke Lighthouse was built in 1823 and is the second oldest in the nation. The Ocracoke Preservation Society Museum, housed in a 1900s-era building, preserves the island’s unique history and culture.

The Cape Hatteras Lighthouse is the tallest one in America at approximately 208 feet. It began its service in 1870. In July 1999, the lighthouse was moved from the ocean’s edge to 2,900 feet inland. Just west of the lighthouse is the Frisco Native American Museum with a gallery dedicated to local tribes.

Visiting the Elizabeth II Replica

The twelve-mile-long Roanoke Island, situated between the mainland and Nags Head, includes the historic towns of Manteo — the site of the first English settlement in America- and the rustic fishing village of Wanchese. The Elizabeth II Historic Site features a 69-foot, square-rigged sailing vessel berthed at Manteo’s Pirates’ Cove, representing vessels that brought the first colonists to the New World in 1585. At the North Carolina Aquarium, sharks, loggerhead turtles, starfish and sea urchins are among the living marine creatures on exhibit, offering a great marine education and research facility.

Historic Roanoke Island

Also on Roanoke Island is the 144-acre Fort Raleigh National Historic Site, where Sir Walter Raleigh’s explorers and colonists tried to establish settlements in 1585. In 1587, Raleigh sent John White with 117 men, women and children, who sailed from Plymouth, England, to begin a new life, but three years later, they vanished without a trace, beginning a 400-year-old mystery about the lost English colony that has haunted this region. Historians today offer various theories and are still combing the land for clues about their fate. Hatteras Island was inhabited by the small Native American tribe, the Croatoans, who had good relations with the English settlers and could have welcomed them, in contrast to other Native American tribes on the mainland with whom the settlers had hostile interactions. It’s a fascinating story to follow. It is shared in TV documentaries and in the “Lost Colony” symphonic outdoor drama, a Pulitzer-Prize winner created by Paul Green, presented almost nightly from early June to late August.

The wildlife includes wild ducks, seagulls and snow geese, as well as wild ponies on Ocracoke Island. The golden sea oats flourish on the dunes and beaches and while they sway in the breezes, they protect the shores from erosion. Many also collect driftwood on the Outer Banks beaches.

Outer Banks Shelling on Shackleford Banks

South of Ocracoke Island starts a long stretch of barrier Islands part of the 56-mile-long Cape Lookout National Seashore. At its southern point stands Cape Lookout Lighthouse. There are no roads or bridges to these islands; access is only by toll ferry or private boat. The visitor center on Harkers Island can be reached from Beaufort. From the Cape Lookout Lighthouse, the islands turn west and form Shackleford Banks and Bogue Banks, where Atlantic Beach and historic Fort Macon are located.

Shackleford Banks, part of Cape Lookout National Seashore, was obtained by the National Park Service (NPS) in the 1960s. This skinny barrier island was first acquired by a Virginia planter named John Shackleford in 1713, who was granted several large tracts of coastal North Carolina land. In the late 1800s, it was known as “Diamond City” with about 500 permanent residents, famous for the excellent salted mullet fish they packed and shipped. But a couple of years after the disastrous 1899 hurricane, all residents were gone.

Shackleford Banks is a picturesque and undeveloped barrier island where visitors can enjoy the peacefulness of the pristine beach shoreline and Outer Banks shelling. It is only accessible by a twenty-minute scenic boat ride, served by the Island Express Ferry Service, the only taxi ferry commissioned by the NPS, which departs every 15 to 30 minutes from downtown Beaufort or the Harkers Island Visitor Center.

Being in the path of the Gulf Stream, Labrador Currents, and the annual hurricanes, Shackleford Banks is perfectly situated for many shells to be found along the beaches. Perfect times for Outer Banks shelling are after high or low tides or when the waters calm down after hurricane storms.

Atlantic Whelks and Other Outer Banks Shelling Finds

The Atlantic whelk is a spiral, tapered shell species that comes in many shapes and sizes, up to 30 centimeters in length. They are found in abundance on Shackleford Banks.

The Scotch bonnet (Semicassis granulata) is a sea snail, an egg-shaped species, about two to four inches long with a yellow, orange or brown squarish spots pattern. It was named for its coloration pattern, similar to Scottish tartan fabric or the shape of a tam o’shanter, the traditional Scottish wool bonnet. It was voted in 1965 as the official state shell, chosen to recognize the contributions of early Scottish settlers in North Carolina.

Olive shells are smooth, shiny, elongated, oval shells that come in various colors and patterns. Auger shells, related to cone shells and turrids, are high-spired shells resembling rock drill bits. Moon snails, also known as necklace shells, are mostly globular in shape.

Wampum Shells: Crafting with Ocean-Tumbled Treasures from Outer Banks Shelling

At the Outer Banks, it’s easy to collect many small ocean-tumbled pieces of the violet-and-white quahog clamshell known as wampum, a Northern Atlantic hard-shelled clam. It was held in high esteem for its naturally occurring rare purple color by the Native Americans, who produced thousands of small, cylindrical beads to decorate bib necklaces or belts.

The ocean is a natural tumbler, smoothing the broken shells’ rough edges and bringing them to a matte finish. The beautiful, bright violet-white striped pieces are easily spotted on the sandy beaches while Outer Banks shelling. Pieces that show violet on both sides are the most desirable.

When you are ready to work with your shells after Outer Banks shelling, sort them by size, color and stripes. It’s not as easy as you may think because two pieces are rarely identical. The shells are fairly easy to drill with diamond drills, but remember to always run water to avoid inhaling the toxic shell dust. They can then be set or wire-wrapped.

Sand Dollars: Coastal Coins of the Outer Banks

Sand dollars, also known as sea cookies, are a flat, burrowing species of sea urchin belonging to the order of Clypeasteroida. The dried and dead sand dollar skeleton is a hard shell made of calcium carbonate. The shape of the white, sun-bleached sand dollars is reminiscent of a silver coin – a Spanish dollar – hence the name.

Sand dollars average three to five inches in diameter. Finding a complete sand dollar fossil on the beach is a coveted treasure among beachcombers. Just make sure it is not alive (those are coated with spines), as it is illegal in many states to take a living sand dollar. The sand dollar’s markings are also connected with local legends and stories.

Sand Dollar Island is a quick ferry away from Morehead City, located on the mainland across Atlantic Beach. Technically a large sandbar accessible only at low tide, Sand Dollar Island is home to the biggest concentration of sand dollars along the North Carolina Coast because of shallow tidal pools.

Outer Banks Shelling: Final Thoughts

From windswept dunes to crystal-laden shores, Outer Banks shelling is more than a pastime—it’s a journey through natural beauty, history, and personal discovery. Whether you’re beachcombing for Scotch bonnets, crafting with wampum, or climbing lighthouse steps between low tides, these barrier islands offer endless treasures waiting to be found, cherished, and shared.

This article about Outer Banks shelling previously appeared in Rock & Gem magazine. Story and photos by Helen Serras-Herman. Click here to subscribe.