By Bob Jones

I’ve been involved with mineral collecting for over 80 years, I’ve traveled the world and visited countless museums. I’ve seen all sorts of public and private collections and enjoyed participating in more mineral shows than I can count. These experiences exposed me to literally hundreds of thousands of odd, intriguing, and gorgeous mineral specimens of every variety. As I handled many of them, I admired each one. Over time, I’ve developed an idea of which species are my favorites, and of these, I certainly have my favorite specimens.

Among my most favorite minerals is epidote. This selection surprises many because, as mineral specimens go, epidotes are not as significant as many others and certainly lacks some visual appeal. Indeed, there are more colorful, more beautiful, more valuable minerals that rank higher on my list than a small dark green cluster of slender epidote crystals with slanted terminations that is part of the Yale University collection. The epidote mineral in the Yale collection is insignificant and happens to be a fake! Yet, it is one of my favorites because it caught my eye among the hundreds of specimens featured in the very first mineral collection I saw. I was 10, and during my visit to the Yale Peabody Museum, that specimen caught my attention and stirred my interest in minerals and the hobby. I remember the small Austrian epidote best from that visit, which also included an array of intriguing items.

During that first visit to the Yale Peabody Museum, I investigated the dinosaurs on the first floor moving to the Mineral Hall. The collection was assembled by revered scientists the Sillimans and James Dana, who made incredible mineralogy contributions.

Mineral-Filled Memories

Once in the Mineral Hall, I was captivated by what I saw as I walked the aisles between case after case filled with amazing mineral specimens. I had never even seen a mineral up to that day. The display contained hundreds of stunning specimens. Among the more memorable examples was a 22-inch sword-like Japanese stibnite, lovely, colorful wulfenite, sparkling blue azurite, greenish pyromorphite, snow-white calcite, and quartz specimens.

Although I can only describe a few of those specimens I saw that day, that little epidote has a special place in my memory. The specimen represents the key that opened my mind to the world of minerals and mineral collecting. Little did I realize I would end up assembling a large mineral collection and research minerals as part of my Master’s Thesis, published more than twenty years later.

While researching the specimen, which measured about three inches and included a dark green tangle of hair crystals, I realized the hairy crystals were actinolite variety byssilite. Protruding out of those hairy crystal fibers were several one-inch-long dark green terminated epidote crystals. It caught my eye because the thing looked like a cross between an anemone and a hedgehog. It fascinated me that something that strange could be natural and had come out of the ground unscathed. It stirred my curiosity to learn more about minerals.

To my regret, some years later, I learned that the Austrian epidote of my memory had actually been put together manually and was, in effect, fake! I’m not sure who created the specimen. However, I learned that locals of Intersasbactal, Austria, often assembled specimens to sell to visiting tourists who came to the source of the world’s finest epidote specimens. My little hedgehog epidote had been “constructed,” but no matter. That specimen, and others at Yale, are why I started rock collecting, which led to writing, traveling, and lecturing in this greatest of all hobbies.

The byssolite and epidote crystals in the little “fake” specimen were from Knappenwand, Untersaltzbachtal, Austria, which is not far from the country’s famous salt mines. Knappenwand has long been the source of the world’s finest epidote found in substantial quantities since the mid-1800s. For centuries, the Austrian source has been the most prolific producer of epidote, until recent discoveries in Pakistan.

Exploring Austria’s Epidote Deposits

Before we talk about Pakistanian, let’s look at some aspects of the Austrian deposit. The host rock is an epidote schistose rock — the result of hydrothermal alteration during secondary metamorphic action. Epidote is a prevalent rock-forming mineral formed in various localities ranging from medium-temperature metamorphic environments to skarns, pegmatites, and contact metamorphic limestone.

The Austrian epidote crystals were found in crystallized clefts in schistose rock with amphibolite rock intruded by aplite, a fine-grained type of granite. Such an environment holds various elements necessary for epidote to form. The deposit was discovered when prospectors were looking for potential ore deposits. Once found, the Austrian epidote crystals set the standard for excellence of this common mineral that was not equalled until Pakistan began producing.

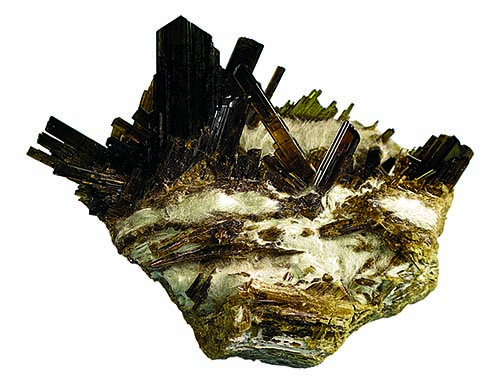

Austrian crystals are elongate, range in color from pale yellow-brown to pale to dark yellow-green. They generally have slanted terminations as one prism face is slightly longer. Crystals frequently show shallow vertical striations and readily develop clusters of sub-parallel growth in lathe-like crystals up to a foot in length.

Even the name, epidote, suggests how these crystals terminate with slanted termination faces. The Greek word epidosis means “addition,” since one side of a prism seems to have an added length resulting in the slanted termination.

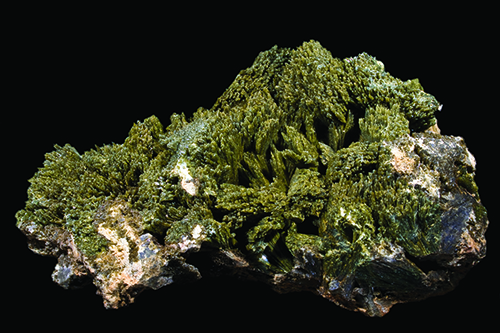

Epidote crystals appear in various forms. Crystals can be pyramidal, tabular to elongate, acicular, blocky, or massive. Twinning is common and relatively easy to identify by a chevron pattern seen on the crystal termination. Fine crystals are also known to appear dark green to nearly black in color. In uncommon cases, epidote can be faceted, but it tends to be quite dark once cut. The yellowish color shows best in thin slivers or the edges of gemmy crystals. When massive or fibrous, epidote’s color is most often a pistachio green. Pale green crystalline epidote is found abundantly in cracks and as coatings on faces of host rocks.

Often when collecting, you may encounter rocks with a greenish coating. What you are seeing is epidote more often than not. The rocks of the Upper Michigan copper deposits and the rocks in zeolite localities very often show this green epidote coating.

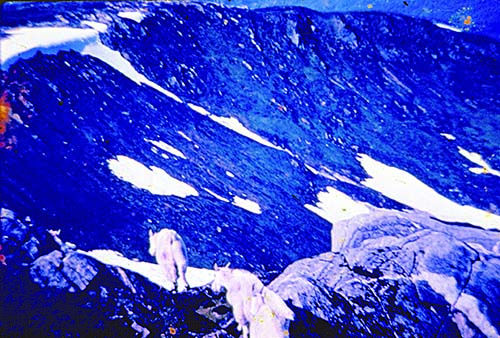

In the U.S., quantities of fine epidote were found in a skarn deposit on Green Monster Mountain, Alaska. Epidote was revealed during copper mining here in the 1930s, and the Smithsonian mounted a specimen-collecting trip to study and collect on Green Monster Mountain.

One of my collecting regrets is never accepting a trip to Green Monster, although I was invited several times by two Alaskan friends, Lee Myers and Virg Gile. These two fellows braved collecting Green Monster many times, dealing with the constant rain, cold, wind, isolation, and the bear population.

To reach the collecting site on Green Monster, which is a skarn deposit, you fly in by floatplane and land on a lake at the base of the mountain. An arduous climb gets you to the deposit, and if luck is on your side, the local bears won’t bother you.

In addition to Alaska’s Green Mountain, fine epidote has surfaced in Connecticut; Lemhi County, Idaho; Riverside, California; and Colorado. The Colorado locality was worked for crystals for a time, but nothing has recently come from these localities. The same is true of Baja California Norte, at Gavilanoes, Castillo Real, Mexico, which produced quantities of single, well-terminated, inch-long blades with other species. Arundel, Norway, and Alla Valley, Italy, yielded fine crystals seldom seen today except when a collection is broken up and offered for sale.

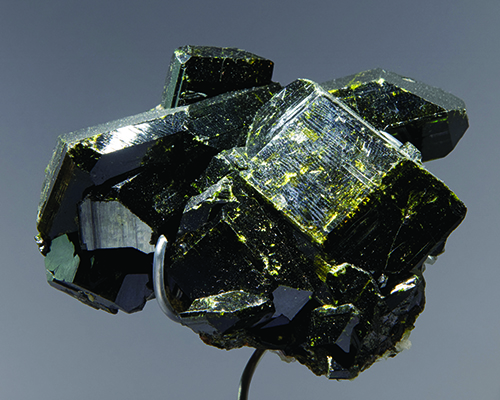

Fortunately, when Pakistan started producing fine pegmatite minerals, it also yielded specimens of epidote, which many collectors, including this writer, feel rival the Austrian epidote specimens. Their crystal form, color, elongate crystals, and sub-parallel clusters are every bit as nice as Austria’s best.

Pakistan epidote specimens first appeared from the Zard Mountains, Kharan, but it was not until alpine fissures were discovered in the Turmiq Valley near Shigar Valley that several deposits were found. The finest examples of epidote were found at Alchuri and Dassau in the Surdu District of Pakistan’s Northern areas.

Epidote is one of those species that offers collectors a nice variety of crystal forms from elongated to blocky crystals, from a lovely yellow-brown to yellow-green to nearly black. Its crystal forms vary, so you can collect a dozen epidotes, and they are all different in color, shape, and associations with the added appeal of fine twinning. A suite of epidote crystals from worldwide sources has great eye appeal and is well worth owning.

Author: Bob Jones

Holds the Carnegie Mineralogical Award, is a member of the Rockhound Hall of Fame, and has been writing for Rock & Gem since its inception. He lectures about minerals, and has written several books and video scripts.

Holds the Carnegie Mineralogical Award, is a member of the Rockhound Hall of Fame, and has been writing for Rock & Gem since its inception. He lectures about minerals, and has written several books and video scripts.

If you enjoyed what you’ve read here we invite you to consider signing up for the FREE Rock & Gem weekly newsletter. Learn more>>>

In addition, we invite you to consider subscribing to Rock & Gem magazine. The cost for a one-year U.S. subscription (12 issues) is $29.95. Learn more >>>

Hide i

Hide i